In Gaza, surgeons are operating by flashlights, rationing anesthetics, and running out of precious fuel needed to keep patients alive.

As the World Health Organization reports that more than one-third of the city’s hospitals are no longer operating and Israel’s bombing continues, health care professionals fear the worst.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

“The health system here is in its last throes before it completely boots down. If the electricity goes, that’s it. It just becomes a mass grave,” says Dr. Ghassan Abu-Sittah, a British-Palestinian plastic and reconstructive surgeon who has been working at Al-Shifa hospital over the last two weeks. “There’s no hospital, if there’s no electricity.”

Read More: ‘Our Death Is Pending.’ Stories of Loss and Grief From Gaza

Right now, his sense is that it will be “days, rather than weeks,” until Al-Shifa runs out of fuel needed to keep the hospital running. Palestine’s Ministry of Health said Tuesday that hospital generators will stop running in 48 hours, and aid workers tell TIME that the city is expected to run out of fuel on Wednesday evening.

The situation is particularly dire for neonatal babies. Dr. Hatem Edhair, the head of the neonatal intensive care unit at Nasser Medical Complex in Khan Younis, fears that electricity shutting off will mean five babies dependent on ventilators will die. “If there is no electricity, it means the end of their life… because oxygen will not be available,” he says.

Dr. Ahmed Mhanna, manager of Al-Awda hospitals in northern Gaza, said Monday that the hospital only had enough fuel to run another three to four days. They have been relying on two generators that have been consuming more than 13 liters per hour, he says. “If there’s no fuel, it means the generator will stop. If the generator will stop, the hospital will stop. We will close,” he says.

Mhanna is unfazed by the sound of a blast while on a phone interview with TIME. Asked whether he wants to cut the call, he responds: “No, it’s OK: they are bombing everywhere all the time.”

“We are feeling absolutely unsafe in the hospital. We are worried, we are afraid, we are human beings but we cannot do anything except continue our mission with our patients,” he says.

So far, Israeli attacks have killed more than 6,400 people and injured more than 17,000 people in Gaza, according to the Palestinian Ministry of Health run out of the West Bank. More than half are women and children. The Palestinian Ministry of Health also reports 73 medical personnel have been killed, more than 100 have been wounded, and 25 ambulances are out of service.

The airstrikes follow Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel that killed more than 1,400 people. As the U.S. works to funnels more than $14 billion in aid for Israel, pro-Palestinian advocates and aid groups are calling for a ceasefire with little success.

Read More: The Gaza Healthcare System Is Reportedly on the Brink of Collapse

The sheer number of injured Palestinians means Al-Shifa is operating well beyond its maximum capacity of about 700 patients—instead dealing with between 1,700 to 1,900 people, Abu-Sittah says. Hospital compounds have become makeshift tent cities—not only for patients but also civilians seeking shelter. “You feel that there’s a public health catastrophe waiting to happen,” Abu-Sittah says.

So many people in such a small space, with inadequate access to hygiene and sanitation, can lead to an outbreak of infectious diseases, he says. Having dead bodies remain in the streets is another source of potential infection, health experts warn.

Al-Shifa hospital also can’t sterilize surgical equipment properly. Abu-Sittah has been going out to the corner store to buy bottles of vinegar and laundry detergent to clean wounds. He feels forced to cut some surgeries short because of how many patients he needs to treat. “Everyday you make more and more compromises about what you can and can’t do,” Abu-Sittah says.

Even Edhair’s hospital in Khan Younis in southern Gaza—Israel had ordered a mass evacuation from northern to southern Gaza on Oct. 13—has had its share of nearby explosions. Last week, he says two airstrikes landed near the hospital, causing mothers to flee their rooms, crying. “This is terrifying,” he says. “We all are afraid of war. I want everyone to know we are civilians.” On Monday morning, he found an airstrike just 500 meters from his home, he says. His mother told him not to go to the hospital but he refused to listen.

More than 20 hospitals have been asked to evacuate in the northern Gaza strip, according to the Palestinian Ministry of Health. The Israeli government called Al-Awda hospitals less than a week ago and told Mhanna personally they have to evacuate staff and patients, he says. “I refused, of course, because where can I deal with my patients? All the hospitals in Gaza are overcrowded, people are lying in corridors.”

“A crime is a crime, even if you make it by appointment.”

Dr. Ghassan Abu-Sittah

Al-Shifa Hospital has received similar warnings. “Giving notice by telling hospitals that they need to evacuate—knowing very well that’s not possible—does not make targeting hospitals less of a war crime,” Abu-Sittah says. “A crime is a crime, even if you make it by appointment.”

And as hospitals switch to caring for the victims of recent violence, routine care is almost impossible to provide.

“When we think about war, we often focus on the victims of airstrikes… but ordinary lives don’t stop. Women still go into labor. They still have miscarriages, ectopic pregnancies, preterm births, and hemorrhages,” says Dr. Brenda Kelly, a consultant obstetrician in Oxford, U.K. Many operating theaters in Gaza are now dealing with trauma-related injuries, leaving less room to treat pregnant women.

Read More: What Aid Groups Say Gaza Needs

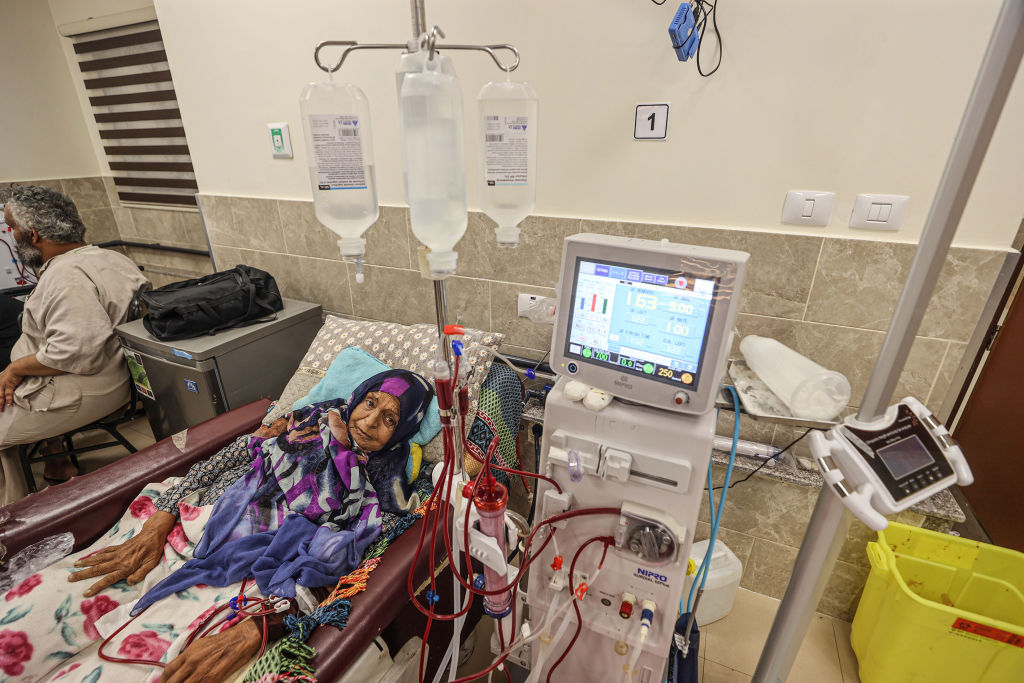

Melanie Ward, CEO of Medical Aid for Palestinians, a U.K. based nonprofit, is particularly worried about disruptions to routine care, such as kidney dialysis and cancer. More than 1,000 kidney dialysis patients have had their session time reduced from four hours to 2.5 hours per patient, according to Palestine’s Ministry of Health. About 9,000 cancer patients rely on chemotherapy to stay alive and the only hospital providing this service is running on a single generator expected to stop working within 24-48 hours, the ministry noted.

She says the group has already released more than half a million dollars worth of medical supplies to hospitals across Gaza. But it’s not enough. “Some operations have been conducted without anesthesia, which I find barbaric,” she says. “We do not live in the middle ages.”

Dr. Omar Abdel-Mannan, a British-Egyptian senior pediatric neurology resident in London, co-founded the social media account @GazaMedicVoices, which shares firsthand accounts from health care professionals in the city. He says hospitals in Gaza were running on fumes even before recent airstrikes, as the city has been facing a blockade for more than a decade.

One story that haunts Abdel-Mannan is from a pediatric intensive care doctor in Gaza who said she was torn between helping two patients who arrived at the intensive care unit. “She had to basically let one not survive and choose the other one to keep them alive,” he says. “She was heartbroken over the idea that she’s having to make these decisions that almost feel like you’re playing God…because of the sheer volume of patients coming through the door.”

In the meantime, doctors are feeling powerless—not only about dwindling supplies but about the scale of casualties. On Monday, after Abu-Sittah finished operating on a young Palestinian girl, he tried to console her, saying that her procedure went well and she was alright. “She said to me: things will never be alright: they killed my mom and dad.”