This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. The US House of Representatives elected a leader yesterday, and the market didn’t care. It was focused instead on bloodying up tech stocks. Alphabet fell 10 per cent yesterday after cloud computing sales undershot. Meta stock also sold off after-hours, despite crushing earnings expectations. More on this below. Email us: robert.armstrong and ethan.wu.

The mag-seven aren’t as new as you might think

So far this year, the magnificent seven Big Tech stocks account for all stock market returns, everywhere. Well, sort of. The MSCI world index is up for the year, but when the seven are taken out, it is down. So wrote Nicholas Megaw in the FT on Tuesday:

The seven have added almost $4tn in market capitalisation in 2023, compared with $3.4tn in gains for the MSCI index as a whole. They have added a combined 40 points to the index, which has risen 37 points overall . . . The largest 10 stocks make up almost 19 per cent of the index, up from 8 per cent in 2013.

Are the magnificent seven towering over world markets because they are in a valuation bubble? Possibly, but I’d guess not. One can argue about whether they’re overpriced. Tesla, Microsoft and Apple look overextended and I don’t really understand how Amazon and Nvidia are valued. Yesterday’s rough treatment of Alphabet after it reported marginally weaker results than expected (the stock fell by a tenth) shows that its valuation is quite demanding. Even Meta, the lowest valuation in the group, got dinged after broadly strong earnings, possibly for its aggressive spending on data centres. Treated as one company, the mag-seven have a market cap of $10.6tn, a weighted average growth rate of 23 per cent and a 2023 price/earnings ratio of 37. That looks too expensive, but on the other hand, these are great companies. If it’s a bubble, it’s not a huge one.

What, then, is the explanation for the seven’s dominance? One possibly worth considering is that it is just normal for a small number of companies to generate the majority of shareholder returns over time, and therefore it is unsurprising that a few companies should dominate US and global indices.

Keep in mind the results of Hendrik Bessembinder’s famous papers about where returns come from. In “Shareholder Wealth Enhancement, 1926 to 2022”, Bessembinder, professor at Arizona State University, found that while over the study period stocks created a huge amount of wealth ($55tn!), most stocks (almost 60 per cent) destroyed wealth overall. (He measures wealth as returns over the one-month Treasury rate, and assumes dividends are not reinvested.) Most importantly, a small number of stocks in the sample generated a huge portion of the total wealth created: 50 firms have accounted for 43 per cent of the wealth created in US stock markets since 1926, and 10 account for 20 per cent of the total. Here is the top 10, with four of the mag-seven represented in the top five:

It is inevitable that the companies that created the most wealth in markets are mostly businesses that are dominant today, inasmuch as the world economy and markets have grown over the last century. Still, the extraordinary concentration that Bessembinder documents reflects the fact that stock returns are far from normally distributed, and we should not be surprised when a few companies explain the overall direction of markets.

Bessembinder notes that the concentration of market capitalisation, understood as the amount of total market capitalisation accounted for by the five largest companies, is about the same as it was in 1974, at about 15 per cent, though it has varied quite a bit in the intervening years. At the same time, though, the concentration of wealth creation at the very top few businesses has increased since 2016. So the structure of the corporate economy may be changing. What that change is driven by — technology? competitive dynamics? — is worth thinking about. But the base rate should always be kept in mind: stock market returns are by nature very, very concentrated.

Maybe the economy will be OK

This strikes us as a big deal:

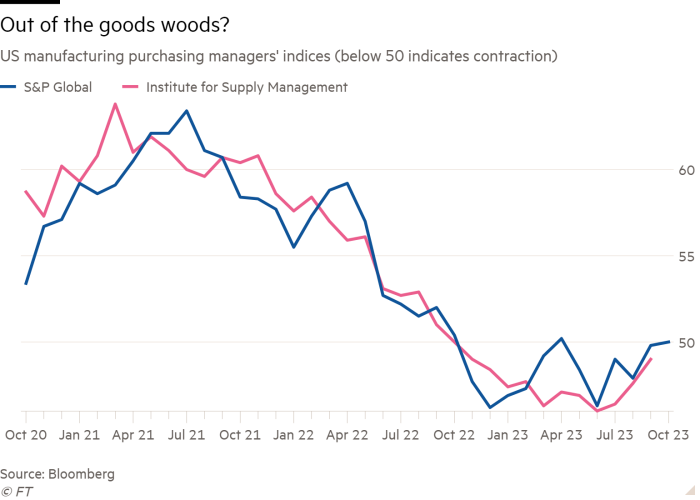

Manufacturing, which has for a year has been a soft spot for the US economy, is by one measure leaving contraction territory. S&P Global’s preliminary manufacturing PMI survey, published on Tuesday, ticked up to 50. This index has presented headfakes before; an upturn this past April turned out to be noise. But as you can see in the chart above, both the S&P and ISM indices seem to be pointing to a bottom in manufacturing activity that is now behind us.

Many times this cycle, we have stared at the economic data in bafflement. In no small part, this is because of the unstable balance between goods and services spending. Now, that appears to be stabilising. In inflation-adjusted terms, spending on goods has gone from about 32 per cent of consumption before the pandemic to 35 per cent today, arguably reflecting the long shadow of remote work. Consistent growth in real services consumption has finally been joined by rising goods spending (despite a dip in the latest August data).

The result is a turnaround in manufacturers’ fortunes. Nor is it the only part of the economy that looks strong. Throw in retail sales rising 2 per cent in the past three months, Visa card volume growth solid at 9 per cent, rock-bottom unemployment insurance claims, and the New York Fed high-frequency economic data tracker at a sturdy and rising 2 per cent. Today’s GDP numbers will almost certainly come in hot, too. Could we be seeing growth re-accelerate?

Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics urges against that interpretation. If you look through quarterly volatility, the economy has been growing roughly at its potential, around 2 per cent or so, for a while, he says. Manufacturing’s decline has weighed on growth in the past year, but only a little. At its worst, industrial production fell just 2 per cent in the fourth quarter. Something similar can be said for housing, the other major soft spot. The existing-home market is being squeezed by high mortgage rates, but the effects have been offset by the surge in new home sales, up nearly 20 per cent this year. Housing and manufacturing weakness has been shallow enough to be offset by robust services spending.

It is natural, then, that consumers are the centre of attention. For now, they seem fine. One prominent argument against consumer strength continuing — the resumption of student loan payments — looks exaggerated. A New York Fed estimate published last week found this will shave a hardly noticeable 0.1pp off monthly nominal consumption. Another knock — rising delinquencies on card and auto loans — may be misleading too, argues Zandi. His data from Equifax suggests that loans originated this year have a lower delinquency rate than those originated in 2021 and 2022, the flipside of stricter underwriting standards. Over time, that should result in lower headline delinquencies, perhaps in the second quarter of next year.

There are always risks. One could mention elevated petrol prices, or a further deterioration in housing from 8 per cent mortgage rates, or inflation turning up. But a strong economy buys the Fed a lot of time to ponder inflation’s destiny. Maybe in the end it will all be OK? Email us if you disagree. (Ethan Wu)

One good read

Understatement of the year: “We are a little short on deliverables.”

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, hosted by Ethan Wu and Katie Martin, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Checkout latest world news below links :

World News || Latest News || U.S. News

The post Top-heavy markets are normal appeared first on WorldNewsEra.