Since attaining the premiership in August, Thai Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin has branded himself the nation’s chief “salesman,” traveling around the world to court foreign investments to boost Thailand’s stagnant economy. This week, as global leaders descend on San Francisco for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit, he’s bringing perhaps his biggest pitch yet to a new crowd of potential investors: Landbridge, a $28 billion infrastructure project that offers an alternative trade route through Southeast Asia that would bypass one of the world’s busiest sea lanes.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

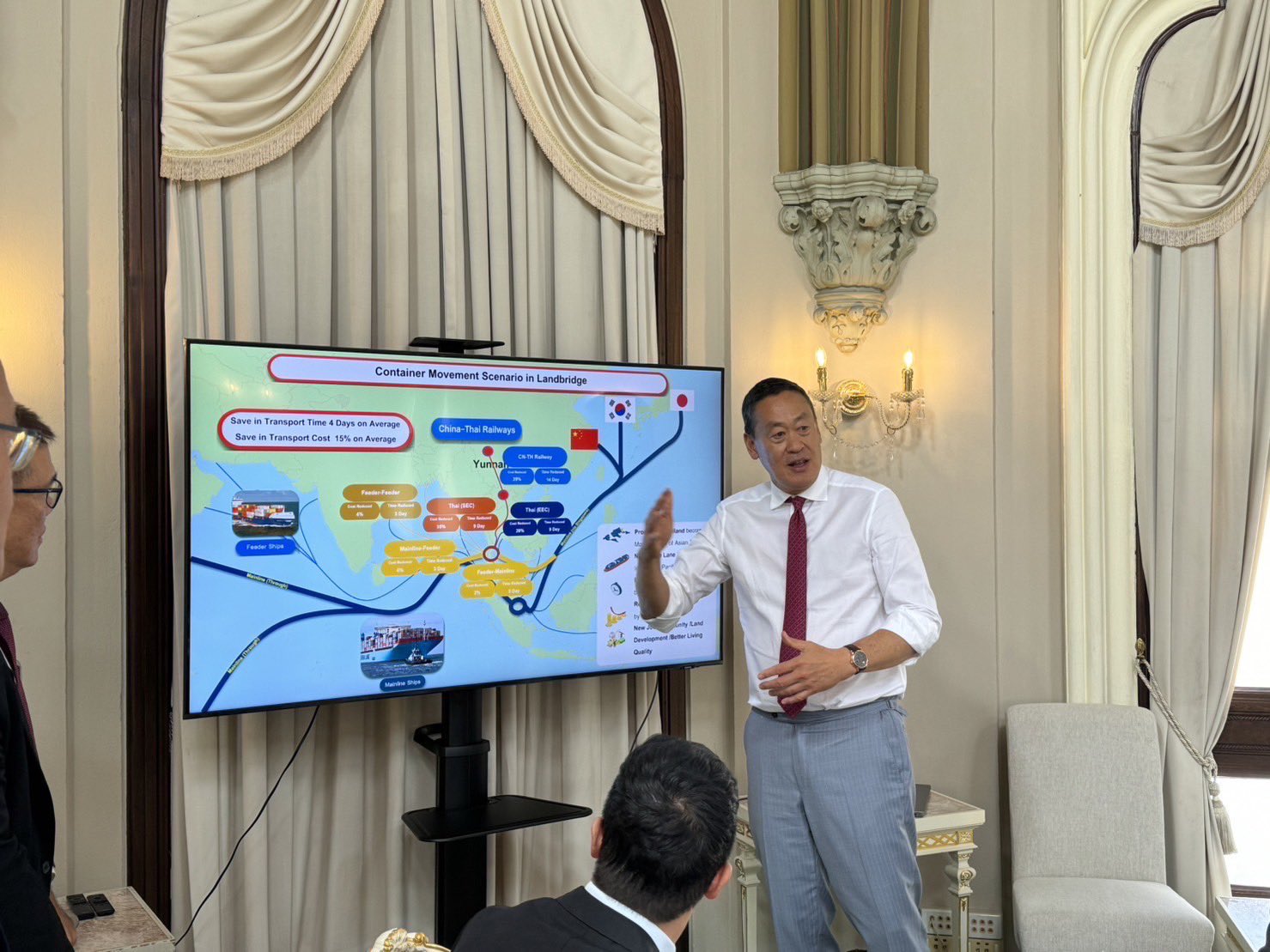

The proposed 100-kilometer bridge that would cut across the Kra Isthmus, the narrowest part of the Malay Peninsula, would connect the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean without requiring ships to sail down along the tip of Singapore through the narrow Malacca Strait, which is known to experience congestion, collisions, and even piracy. The Landbridge is estimated by Thai authorities to cut transport duration by an average of four days and lower shipping costs by 15%.

The idea of creating an alternative route to the crowded Malacca Strait may be ambitious, but it’s not at all new: plans for such a shortcut, whether by land bridge or canal, date at least to the 17th century, in the Ayutthaya kingdom predating modern Thailand. More recently, similar ideas were also toyed with by Srettha’s predecessors—including the administrations of Prayut Chan-o-cha and Thaksin Shinawatra—but were repeatedly shelved due to concerns about the projects’ impacts on wildlife and local communities.

Read More: Thailand’s Newest UNESCO World Heritage Site Is Being Overrun by Sacrilegious Tourists

The Landbridge project also holds the potential to become a geopolitical flashpoint as competing powers vie for influence in the region, though Srettha appears keen to sidestep such tensions by welcoming any and all investors. While the Thaksin administration’s proposal to build a canal across the Kra Isthmus in the early 2000s reportedly attracted investment interest from several East Asian countries, including China, Srettha has now gone further than his predecessors by also looking to the West to secure funding for the project.

Srettha previously pitched the Landbridge to Chinese Premier Li Qiang and Chinese investors in October during the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, where Chinese investors as well as investors from Saudi Arabia reportedly showed interest. In San Francisco this week, at his “Thailand Landbridge Roadshow,” Srettha stressed to U.S. investors how the proposed project, which Thailand aims to complete by 2039, would maintain the flow of goods as the capacity of the Malacca Strait faces increasing pressure.

“It’s important for Srettha to make the most of APEC, and pitching the Landbridge project to the West restores Thailand’s traditional delicate juggling of Great Power relations,” Mark S. Cogan, an associate professor of peace and conflict studies at Japan’s Kansai Gaidai University, tells TIME.

In a statement on Monday, Srettha said, “I believe this presents an unprecedented opportunity to invest in this commercially and strategically important project that connects the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean, connecting people in the East with the West.”

What seems top of mind for Srettha is the domestic impact the project could have: the Landbridge, he says, is expected to create 280,000 jobs and increase Thailand’s GDP by 5.5% per year when completed.

Read More: After Awkward Ascension, Thailand’s New Prime Minister Tries Old-Fashioned Populism

But while it’s too soon to tell if Western investors will take up Srettha’s offer, Cogan warns that there are political considerations that come with foreign investment in the Landbridge project that may ultimately become a stumbling block for Thailand.

“The Landbridge, if there are Western investors, will demand much more scrutiny in terms of environmental impacts, potential disruptions to the south [of Thailand], and how debt to foreign investors will affect Thailand’s near-term stability.”

The Prime Minister’s current zeal for the project, Cogan adds, reveals “that as Thailand’s ‘traveling salesman,’ Srettha is thinking about both optics and short-term gains.”