One of the most important people in Israel right now is a 22-year-old military press officer. In recent weeks, Masha Michelson has become the face of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) on social media. With no combat training, Michelson has been trailing Israeli troops in Gaza to document the war from their point of view. On Nov. 19, Michelson, garbed in green military fatigues and a flak jacket, filmed a night-vision tour of the tunnel shafts under Al-Shifa hospital in Gaza City—evidence, she said, of a subterranean terrorist command center where they had found a cache of weapons—and posted it through the IDF’s accounts on TikTok, Instagram, and X, platforms where young audiences are increasingly turning against Israel’s war to destroy Hamas. “When you need to address the world,” Michelson tells TIME, “they’re more likely to listen to someone who looks like them.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

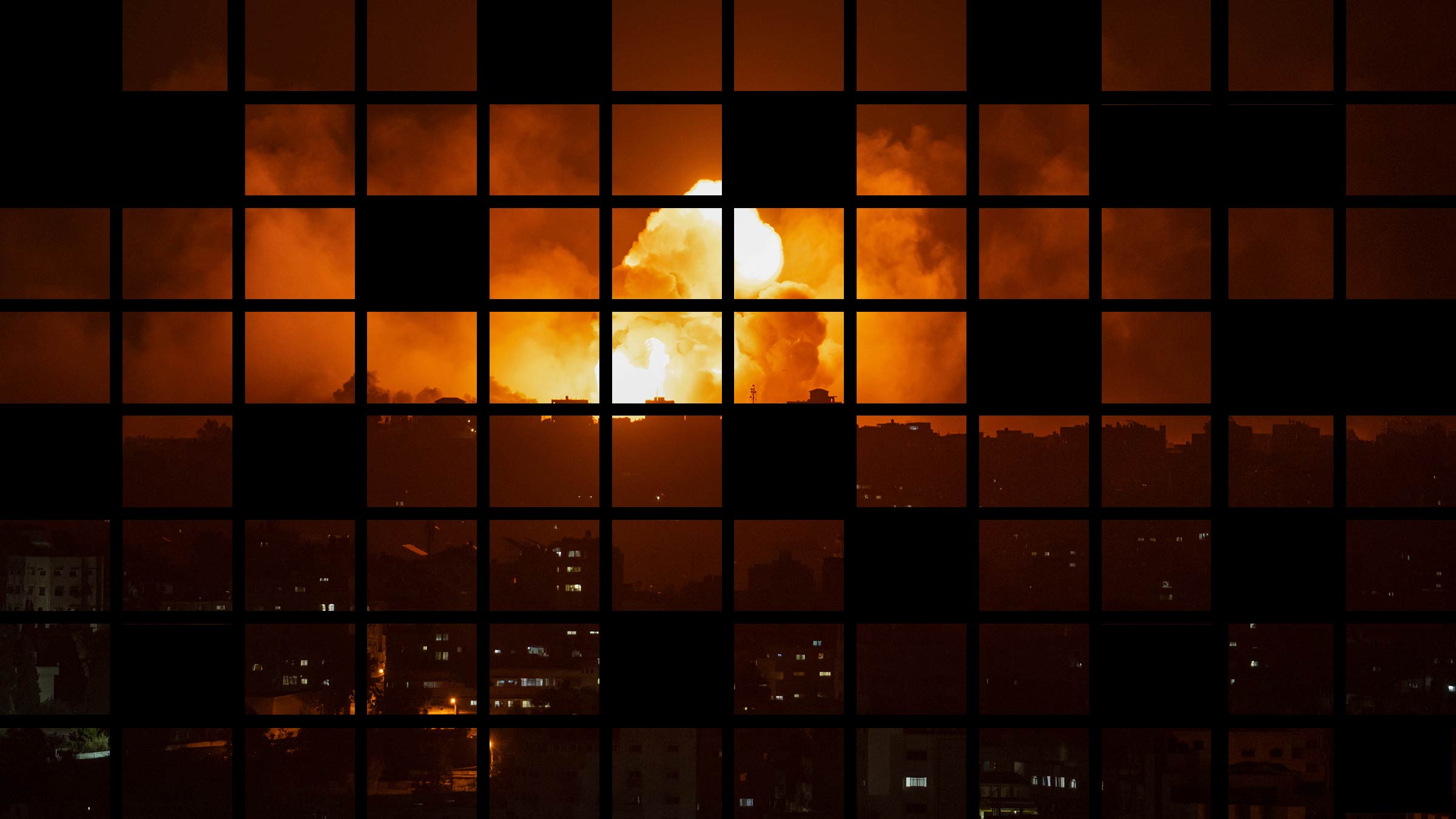

Getting the world to listen is one thing; convincing people is another. Four days before Michelson’s tunnel tour, Israel had concluded a days-long siege of Al-Shifa. The raid forced thousands of sick and injured patients and the doctors and nurses caring for them to evacuate the facility, reportedly resulting in the death of at least six premature babies. To Israel’s critics, it was the latest example of the cost in innocent lives of its offensive. The more than two-month-long bombardment has killed at least 20,000 people, according to the Hamas-run Gaza Health Ministry, which does not distinguish between civilians and combatants. Nearly two million Palestinians have been displaced from their homes. The resulting humanitarian crisis has left the beleaguered coastal enclave all but uninhabitable. Each day, grisly images from the ground in Gaza emerge: mothers and fathers holding their dead children, body parts dug out of the rubble.

To Israel and its supporters, the civilian casualties are a tragic but necessary price that must be paid for the security of the nation-state created after the Holocaust to ensure a haven for Jews in their ancestral homeland. Israel launched the war after Hamas infiltrated Israel on Oct. 7, killing 1,200 people including children and the elderly, taking hundreds of hostages, and committing atrocities including rape. Since then, the group has vowed to repeat the attack. Israel is doing everything it can to avoid the deaths of innocents, its leaders say, but they are unavoidable when Hamas forces use virtually the entire Gazan population, including those in hospitals, as human shields. “How can we fight Hamas without having civilian casualties?” says Yaakov Amidror, a former IDF general. And without destroying Hamas, Israeli leadership argues, you condemn the country to more massacres and send a message to other hostile powers in the region, like Iran, that terrorism works. “That cannot be the future of the Middle East,” agrees Dennis Ross, a former Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiator who served in multiple U.S. administrations.

Much of the world is not convinced. Social media is flooded with wrenching scenes of death and destruction, captured and shared by charismatic citizen journalists who have gained massive audiences with their eyewitness accounts of the war. Videos and images from the ground have been amplified by Hamas sympathizers and state-affiliated Chinese, Russian, and Iranian accounts, according to the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a London-based think tank that monitors online disinformation. A surge of global antisemitism, from college campuses to the halls of power, seeks to discredit and negate Israel’s security concerns. At the same time, some Israeli government officials have undercut their message that the war is designed to minimize civilian casualties by calling for Gaza to be “flattened,” “destroyed” and “erased.” Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu compared the war effort to the biblical story of Amalek, when God tells King Saul to kill every person, including women and children, in the rival nation to ancient Israel.

Amid cratering international support for Israel’s war, there is little debate over which side is winning the battle for hearts and minds. The number of Americans who want the U.S. to take Israel’s side has dropped from 43% in October to 37% in November, according to a survey conducted by the University of Maryland and Ipsos. After tens of thousands of protestors took to the streets in European capitals, some of the continent’s most prominent leaders dialed back their full-fledged embrace of the Israeli campaign, with French President Emmanuel Macron calling on Israel to halt the hostilities. The U.S. remains the only U.N. Security Council member to vote against a call for an immediate ceasefire. And now even the Biden administration, Israel’s staunchest ally and biggest supplier of military aid, is pushing the country to scale back its offensive in a matter of weeks. “They have to be careful,” President Joe Biden said on Dec. 11. “The whole world’s public opinion can shift overnight. We can’t let that happen.”

Interviews with dozens of current and former Israeli and U.S. officials reveal a recognition of the accelerating loss of global public support, and a scramble by the nation’s leaders in response. Behind the social media messaging of spokespeople like Michelson lies a rapidly growing operation to convince the world that Israel is fighting for nothing less than its own survival and is doing what it can to avoid civilian casualties. The IDF’s international communications office has doubled in size to more than 200 people. The IDF has taken reporters and prominent supporters—from Elon Musk and Jerry Seinfeld to a convoy of TikTok influencers—to visit the kibbutzim that became killing fields, in hopes of reminding the world of the scale and depravity of the Oct. 7 attack. The Israeli government has spent millions of dollars on online ad campaigns on platforms ranging from YouTube to the popular online game Angry Birds. Israeli embassies around the world continue to screen for journalists and politicians a 43-minute video of the Hamas atrocities, much of it filmed on the terrorists’ own cameras.

There are signs that the effort is working, to an extent; a Pew Research poll from early December found that 65% of Americans think Hamas is mostly responsible for the war. As the fighting in Gaza moves south and the U.S. pushes its ally to wind down the ground operation, the information war about the war is becoming more important than ever. If Israel wins the military battle but loses the war for worldwide public opinion, it could threaten the durability of American support, damage Israel’s ability to forge and maintain peace with its Arab neighbors, shape the perception of the Jewish state for the next generation, and put the safety and security of the Jewish diaspora at risk. “The stakes of the information war,” says Eylon Levy, an Israeli government spokesman, “are the stakes of the war itself.”

Three days after the Oct. 7 attack, Israeli officials brought a group of international journalists to Kibbutz Kfar Aza, where Hamas killed more than 50 people. The site was still an active crime scene. Corpses were everywhere: Israeli victims wrapped in body bags, Hamas fighters lying where they fell. Military officers led reporters into homes stained with blood, some still filled with mutilated bodies and the charred remains of burned victims. “You could smell the death in the air,” recalls Anshel Pfeffer, a veteran Israeli reporter who writes for The Economist.

The security-conscious IDF had never before allowed the media to explore the site of a terrorist attack with no limitations, with fighting ongoing only a few miles away. The move was part of a strategy to lay the groundwork for the war through hasbara—Israel’s term for public advocacy. In Hebrew, it means “to explain.” Showing the scope and severity of the atrocities would expand the “window of legitimacy” for an invasion of Gaza and the inevitably horrific scenes to follow, Israeli officials said. “It was just like Eisenhower, when he discovered Bergen-Belsen,” says Richard Hecht, the IDF’s international spokesman, invoking the U.S. decision to bring journalists to the liberated Nazi concentration camp in 1945.

Reminding the world what happened on Oct. 7 has been at the heart of Israel’s effort to explain its war effort to an increasingly skeptical public. On social media, at pro-Israel solidarity rallies, and in private meetings with politicians, journalists, and business leaders, officials have highlighted the massacre as an indelible tragedy in Jewish history. The sheer barbarism of it, which included the rape and mutilation of women and the murder of babies, is one reason Israel is determined to eliminate Hamas. If Israel allows Hamas to survive after perpetrating a pogrom, Israel’s leaders reason, it’s only a matter of time until Hamas or other enemies do it again. “There is no future for the Jewish people or the State of Israel in a world where genocidal terrorists can invade Israel and abduct babies from their beds, burn whole families alive, torture children in front of their parents and get away with impunity,” says Levy.

But the hasbara effort is struggling in the face of massive civilian casualties in Gaza. The Islamist group embeds its military installations within densely populated neighborhoods in part to increase civilian casualties, Israeli officials say. “They seek to maximize casualties on their side, because it’s effective,” says Ophir Falk, a foreign policy adviser to Netanyahu. “If there are a lot of civilian casualties on their side, it’s easier for them to win the propaganda war.”

Hamas officials all but acknowledge the strategy, saying they launched the Oct. 7 attack to provoke a major military response by Israel they expected would produce civilian casualties. Israel had been on the cusp of a diplomatic agreement to normalize relations with Saudi Arabia that would have marginalized Iran and its proxies such as Hamas and Hezbollah. Hamas was determined to stop it. “We planned for this because Israel thinks it can make peace with anyone, it can make normalization with any country, it can oppress the Palestinians, so we decided to shock the Israelis in order to wake up others,” Ghazi Hamad, a senior Hamas official, told TIME in the aftermath of the attack. “Now they want to destroy everything. This will cost them. It will cost them very much.”

Some Israeli officials have made statements that have played into that strategy by Hamas. In the first days of the offensive, Israeli military leaders flatly asserted that “the emphasis is on damage and not on accuracy”; Air Force officers told reporters that “we’re not being surgical.” Meanwhile, the IDF’s punishing air and ground campaign rallied millions of young people whose views have been shaped less by the Holocaust than by the decades of Israeli dominion over Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. TikTok and other platforms have become bastions of pro-Palestinian content to youthful audiences who see Israel not as the victim in the conflict but as the oppressor. On Facebook, there were 39 times more #freepalestine posts than #standwithisrael posts. “We were surprised not just on the physical fence on Oct. 7,” says Amichai Chikli, Israel’s Minister for Diaspora Affairs, “but also on the digital fence that we didn’t have.”

Realizing that graphic footage from Gaza was overtaking the Oct. 7 massacre, the IDF began to show the video compilation of footage from the attack, captured on Israeli security cameras and Hamas body cams and phones. After showing it to journalists in Tel Aviv, Israeli officials screened it at embassies and consulates across the globe. One such viewing in Washington on Oct. 30 showed how Hamas militants murdered with glee; in one sequence, the IDF intercepts a recorded phone call a terrorist made to his parents on a victim’s WhatsApp in which he brags about killing 10 Jews.

The IDF has also initiated a campaign to publicize its humanitarian efforts such as allowing aid shipments into Gaza and transporting sick babies to Israeli hospitals. “If we’re creating humanitarian relief, it will give us the time that we need to dismantle Hamas,” Hecht says. “That’s the logic. My goal and my operation is to create international legitimacy.”

Israeli government and military social media channels have posted videos, ads, and graphics that highlight their distribution of Arabic leaflets, phone calls, and text messages warning civilians to flee certain areas. In one TikTok video, the IDF posted raw footage showing officers deciding to hold off on striking a target due to the large number of people, including children, at the site. The IDF has recruited reservists and media experts, doubling its international press office that communicates in 14 languages. Other units, such as the National Public Diplomacy Directorate, have brought in new spokespeople, such as Levy, to help make the case to the world.

Part of Israel’s strategy has been to argue it has a legitimate need to attack civilian targets. That was most resonant on Nov. 15, when Israel raided Shifa hospital. The Israeli wartime cabinet held multiple meetings before green-lighting the strike, according to Falk. “We have to be absolutely sure, 100%, that the hospital is being used as a control center for terrorists,” says Falk. Under normal circumstances, Israel would bomb a Hamas stronghold, Falk adds, but decided on a ground assault, putting its troops at risk, because it recognized the hospital had civilian patients. “It was important to show the world what was going on,” Falk says of exposing Hamas’ activity at Shifa. “That is part of the information war.”

Once the IDF took over the hospital, they began filming videos inside the tunnels, with officers walking viewers through evidence including weapons and explosives allegedly left behind by Hamas fighters. The IDF then made its case across social media, in a direct address to the audiences most repulsed by the Israeli military campaign. “It was crucial to the operation of the Oct. 7 attack,” Michelson says of the complex, citing the accounts of hostages who were brought back to Shifa and the items from kibbutzim found on the premises. U.S. officials agree the tunnels were used for Hamas command and control. But many remain unconvinced. A recent Washington Post investigation concluded that the IDF had failed to prove that Hamas used the hospitals militarily.

Another aspect of the strategy has been an attempt to get the world to identify with Hamas’s victims. “Imagine it was your grandmother being kidnapped from her home and paraded around by terrorists,” Israel’s social media account asked in a video on Nov. 7. In another, dramatized by actors, a woman seeking to report sexual violence by Hamas militants was met with indifference by the international community. Israel’s Foreign Ministry paid for more than $2 million in online ads, containing footage of the Oct. 7 attack. “Israel is fighting battles on many fronts, but the social media front is particularly aggressive,” says Fleur Hassan Nahoum, Jerusalem’s deputy mayor. “And we are painfully outnumbered.”

In early December, senior developers from Tel Aviv’s top tech companies met with Israeli government officials and international communications consultants for a “Hasbara Hackathon” to develop digital tools including a sentiment meter to test whether IDF messaging is resonating with online audiences abroad. “It shows us if the response is positive or negative,” says Jonathan Sagir, one of its organizers. “If the IDF spokesman makes a mistake or the message backfires, it gives us the ability to change it before it spreads too much too fast.”

But it’s an effort that can sometimes run up against the Israelis’ own covert messaging operations. Since the start of the war, Israel has deployed its psyops operation known as the “Influence Unit”—a small but secretive office run out of the IDF that plants stories in the press to shape the perception of the war and send signals to the enemy, senior Israeli officials tell TIME. In some cases, the unit’s tactics can undermine the Israeli government’s hasbara effort. On Dec. 10, it released photographs of Palestinian men, whom the IDF claimed were Hamas terrorists, stripped in their underwear and surrendering to Israeli military forces. It was designed, the Israeli official says, to show Israel winning on the battlefield and to demoralize Hamas members with images of their own men giving up, even though they knew it would come with scathing critiques from the international community and bruising headlines. Says the senior IDF official: “It’s a condemnation that we can suffer.”

Part of the challenge of the organized Israeli military effort is that it is competing with spontaneous global reaction to the horrors of war suffered by innocent civilians. Before Oct. 7, Bisan Owda’s Instagram looked like most 25-year-olds: selfies, pictures of her cats, photos out with friends. Since then, her feed has morphed into a harrowing video diary from Gaza. In a shaky video posted Nov. 3, hundreds of panicked people flood into a courtyard, some carrying bloodied people in their arms. “It’s a massacre, there are thousands of people around,” Owda cries out as she pans the camera to show the aftermath of an Israeli strike. “I was there two minutes ago. It could be me.”

Owda, whose account has gained 3.6 million followers since the war’s outbreak, is one of many young Gazans whose social media has provided vast international audiences with a visceral daily look at life on the ground. They have chronicled the deaths of friends and family, the obliteration of homes and schools, their desperate scramble for medical supplies and food, and their journey to flee south with hundreds of thousands of other displaced Palestinians. Their posts receive tens of thousands of comments a day, with many anxiously checking to make sure they are still alive. “Why do we Palestinians have to film our own country getting bombed and our own people getting killed,” asked Plestia Alaqad, a 22-year-old freelance journalist whose Instagram account has 4.6 million followers, on Nov. 4, “just for the world to watch silently?”

The proliferation of smartphones inside Gaza’s dense urban environment means that Israel’s military operation has generated more real-time data than any contemporary war, including the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, analysts say. They are, for the Israel-Hamas conflict, what television cameras were in the Vietnam era: a new medium through which the world is confronted with the horrors of war.

In that sense, Hamas’ willingness to sacrifice civilian Palestinians for the larger cause of building anti-Israel sentiment worldwide has succeeded beyond measure. Between 61% and 68% of Palestinians killed in Gaza were non-combatants, according to a recent analysis by the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, a far higher proportion of civilian casualties than in previous combat operations in the Gaza Strip. The deluge of graphic content reporting on those casualties has subsequently been exploited by other opponents of Israel and the U.S. in a variety of ways. Hamas propagandists, and state actors like Russia, China and Iran have unleashed a systematic effort to amplify the images and posts through bots and state-affiliated accounts. Some 40,000 fake accounts on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and X pumped out hundreds of posts per day with pro-Hamas narratives after Oct. 7, according to the Tel Aviv-based social media intelligence company, Cyabra. Many of the accounts seem to have been created more than a year before the attack but were activated after Oct. 7, Cyabra claims. In online conversations about Israel and Hamas after the attack, more than 25% of the accounts engaging in the debate were fake, according to the firm’s analysis. “In terms of scale,” says Rafi Mendelson, vice president of Cyabra, “what we’re seeing is definitely unprecedented.”

Accounts tied to China, Iran, and Russia have sought to capitalize on the conflict to spread anti-Western propaganda. Iranian state-linked accounts have glorified Hamas’s attack as an act of resistance against a “neo-colonial” power, and amplified narratives accusing the U.S. of being responsible for Palestinian suffering, according to the Institute for Strategic Dialogue. Russian and Chinese government accounts have promoted similar content, accusing Western countries of turning a blind eye to alleged Israeli war crimes, the think tank says. Compounding the problem for Israel has been the speed with which Hamas and its supporters put out misinformation, leaving the Israelis often playing catch up in the hours it can sometimes take to respond to claims on the internet. “Our main challenge is, we have to verify facts,” Falk says. “Speed matters today, because there’s so many out there on social media.”

Among social media channels, TikTok in particular has been dominated by pro-Palestinian content. For every pro-Israel post on TikTok, there have been 36 pro-Palestinian posts, according to an analysis of hashtags shared with TIME by statistician Anthony Goldbloom, a former chief executive of Kaggle, a data science company now part of Google. Videos posted by young Israeli soldiers seeming to mock Palestinians, smashing childrens’ certificates in Gazan schools or filming themselves throwing a stun grenade into a mosque have been widely amplified to depict the IDF as callous. (The soldier involved in the latter incident was suspended after the video went viral).

The war in Gaza has fueled a wave of antisemitism that was already on the rise. Across the world, people have been filmed tearing down posters of Jewish hostages held in Gaza; student groups and professors have written letters supporting the Oct. 7 massacre; and synagogues have been vandalized with Nazi insignia. In November, hundreds of people stormed an airport in Dagestan chanting antisemitic slogans and waving Palestinian flags while looking for passengers coming off a flight from Tel Aviv. To scholars, the war has become a masquerade to advance expressions of Jew hatred. “When Molotov cocktails are thrown in synagogues, when Holocaust memorials are defaced, when marchers chant against the Jews, when Jewish children are harassed, that’s not fighting for Palestinian rights,” says Deborah Lipstadt, the Biden Administration’s Special Envoy to Combat Anti-Semitism. “That’s antisemitism, pure and simple.”

Israel has also had to contend with its own self-inflicted mistakes. On Oct. 17, major news organizations took Hamas’s word that an explosion outside a hospital was from an Israeli air strike, but U.S. and Israeli intelligence found it was from a misfired Palestinian Islamic Jihad missile. The incident vindicated Israel, but then the country stepped on its own foot. Official Israeli media accounts shared a video of a rocket blazing out of Gaza toward Israel then plummeting midair back into Gaza City. It seemed exculpatory for Israel. But the video was from August 2022. In a WhatsApp group used by more than 50 Israeli communications officials since the war’s outbreak, one member shared an unverified video they saw on the internet, according to sources familiar with the incident. Others were soon posting it on official channels, only to be forced to remove it once it became clear the clip was from a previous conflict. “We do make mistakes,” says Lior Haiat, a spokesman for Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “When we do, we take it off. We understand that our integrity is our main weapon.”

Analysts say Israel’s posting of false or disputed content has eroded trust in the information it has disseminated. A video posted by Israel’s Arabic account, which purported to show a Palestinian nurse condemning Hamas for taking over the Al-Shifa hospital compound, was widely ridiculed for its odd accent, theatrical props, and scripted IDF talking points. (It was deleted soon after). Official Israel accounts have also posted photos and videos of what they falsely claimed were Palestinian “crisis actors” faking injuries, which turned out to be footage from an old Lebanese film. “We really risk regional escalation,” says Alessandro Accorsi, an analyst at International Crisis Group, a think tank in Brussels, “if there is growing doubt over whether Israel’s military is putting out credible information.”

One tragedy of Israel’s war in Gaza is that its central goal—to secure a safe place for Jews—is likely be undermined by the horrors inflicted on innocent Palestinians. That is especially true in America, Israel’s closest ally. While most Americans still sympathize with Israel, the number who disapprove of its military actions in Gaza has increased, according to recent polls. Protests in solidarity with Palestinians are not slowing down, and more and more Democratic lawmakers have voiced their concerns about the large amounts of funding Congress has approved for Israel with few strings attached. (The current memorandum of understanding that guarantees Israel $3.8 billion annually in military aid expires in 2026.) That shift isn’t coming out of nowhere. Last March, Gallup found for the first time in its annual polling that self-identified Democrats sympathized more with the Palestinians than with Israel, 49% versus 38%.

There has also been an unprecedented level of internal rebellion in the Biden administration, with dissent cables, internal petitions, and open letters from employees at the State Department, White House and Capitol Hill showing widening concerns that America’s reputation could be permanently damaged by its support for Israel’s war. “We’re having an almost Vietnam-level movement, a young generation versus the old generation,” says Shibley Telhami, a Palestinian-American scholar and professor at the University of Maryland. In a recent NBC poll, 70% of voters between the ages of 18 to 34 said they disapproved of Biden’s handling of the war. Israeli officials say they fear long-term consequences among younger U.S. audiences who will become the next generation of lawmakers. “I’m talking about the people who are not yet in the circle of decision-makers,” Haiat says. “People who are on the verge of getting to Congress.”

For now, though, Israel’s leaders seem determined to focus on the threat immediately in front of them—Hamas—and less on what may lie ahead. No one is more aware of the risks of that approach than Israeli public affairs officers. With Israel facing growing pressure to define a viable endgame for the war, its efforts to reach audiences around the world have become more urgent. “It’s important that the war ends with Israel enjoying the same support from the free world” as it did before, says Levy, the Israeli government spokesperson. But while the military war between Israel and Hamas may end within weeks or months, the information war is likely to continue long after the last tank rolls out of Gaza. “We’re used to a reality where history is written by the victor,” says Michelson, the 22-year-old IDF press aide. “It’s not the case anymore.”