David Chase is feeling thankful. Twenty-five years after the premiere of the series that cemented his legacy, The Sopranos creator is filled with gratitude that he got to work with actors like James Gandolfini, Edie Falco, and Lorraine Bracco and a writing staff that included future Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner and Terence Winter (Boardwalk Empire). Gratitude for the freedom HBO granted him. And now that the show is a consensus classic, he says, “I have a great deal of gratitude that people still see it. That people seek it out. That people wanna hear about it.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Yet when I ask Chase, during a wide-ranging video chat in December, whether he thinks it would be possible to make The Sopranos today, his reply is firm: “No, I don’t.” For one thing, his friends who’ve produced streaming series keep telling him that TV development is now “really all about money,” he explains. “All these corporations spent billions of dollars chasing after Netflix. And now they’re broke. So everything they produce, they want to do on the cheap.”

Chase is not known for his optimism, particularly with respect to TV. And he’s careful to note that he’s a bit out of the industry loop. But he’s not alone in doubting that the necessary conditions for bringing a project of The Sopranos’ ambition, originality, and cost to fruition exist in streaming-era Hollywood. As John Koblin, who with Felix Gillette co-authored It’s Not TV: The Spectacular Rise, Revolution, and Future of HBO, puts it: a quarter-century after that show kicked off TV’s most recent golden age, “It’s extremely possible that the next few years in television aren’t going to be quite so golden.”

This is the irony that must be acknowledged as we celebrate the 25th anniversary of a series that recast the small screen in its brilliant, violent, psychologically rich image—and whose prescience about the precarious nature of American life in the 21st century has made it even more relevant than it was when it debuted. It’s an indictment of an industry that squandered one of its most fertile creative periods by sacrificing quality for quantity, embracing franchises, genre spectacles, and reality TV. But, as new generations discover The Sopranos, it’s clear that audiences will always hunger for stories that plumb the darkest depths of human nature and societal dysfunction. The question is: Has TV as an art form become too debased to satisfy that hunger again?

The Sopranos arrived on Jan. 10, 1999, with the force of an explosion. And it made TV new again, annihilating the saccharine tropes of the broadcast writers’ rooms where Chase had spent decades on acclaimed shows like The Rockford Files and Northern Exposure. Everything the networks had ever produced (save, perhaps, Twin Peaks) suddenly felt stodgy or artificial by comparison.

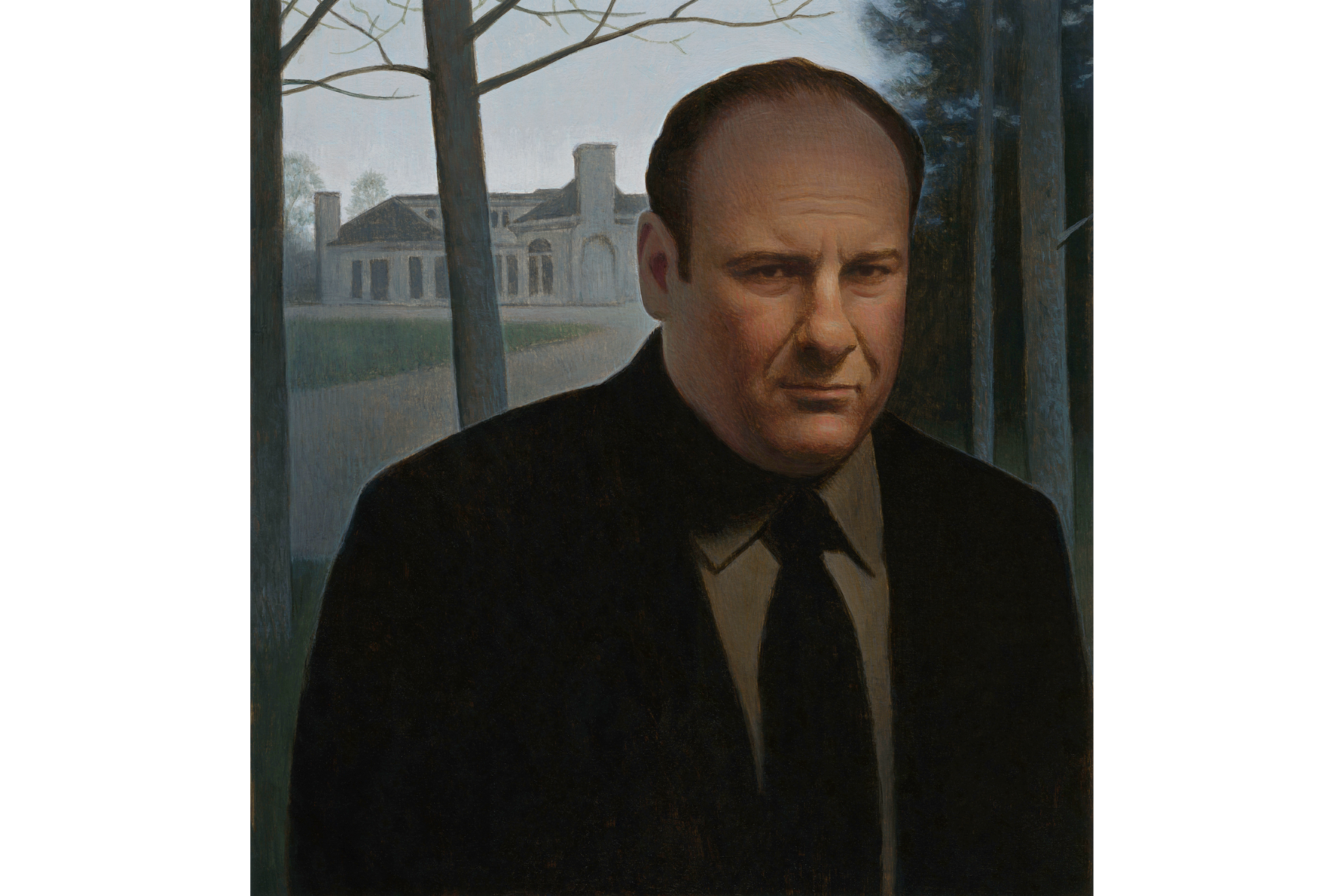

Since then, the series has become such an important chapter in TV history that, especially if you haven’t revisited it in upwards of a decade, it’s easy to take for granted what made it so great. Nominally a gangster show, it certainly featured the guns, goomars, and gory deaths native to the genre. But protagonist Tony Soprano, indelibly embodied by Gandolfini, who died in 2013, wasn’t just a North Jersey mob boss; he was a husband, father, and the son of a cold, manipulative mother (Nancy Marchand). Haunted by sinister dreams that begged for interpretation, his panic attacks landed him in the offices of Dr. Jennifer Melfi (Bracco), a psychiatrist who would become his ambivalent confessor. “It’s good to be in something from the ground floor, but I came too late for that,” he tells her in the pilot. “Lately, I’m getting the feeling that I came in at the end.”

He is talking, obliquely, about America, a place known to Tony’s—and Chase’s—Italian immigrant forebears as the land of opportunity. “I think a lot of people knew, in 1999, that something was wrong,” Chase recalls. “It probably goes way back to the ’60s,” when issues of race, class, and the Vietnam War divided society. “So by the time 1999 came around, the joke was that America had become so greedy and so entitled that even a gangster couldn’t stand it.”

Determined to avoid the didactic tone that was then and is now, again, so common on TV, The Sopranos didn’t evangelize a set of values. It developed layered, conflicted characters and let them disagree. Tony’s wife Carmela, endowed with warmth and grit by Falco, is a Catholic who worries her husband is going to hell—and that by letting his crimes underwrite her lifestyle, she has imperiled her own soul as well. The couple’s relatively sheltered teenage children, high-achieving Meadow (Jamie-Lynn Sigler) and brooding A.J. (Robert Iler), can sound hopelessly naive when contrasted with their father’s lethal pragmatism. Yet their adolescent obsessions with fairness offer a bracing contrast to his brutality.

Along with thoughtful writing and career-making performances by a huge ensemble of mostly unknown actors, The Sopranos characters read as a genuine family (nuclear, extended, crime) because the show made a point of almost exclusively casting Italian Americans from the tri-state area. They “could have been at my house, as a kid, for Christmas,” Chase says. For Falco, this familiarity gave her a unique “comfort level” on set. “There are all these people that could have been family members,” she recalls. “I’ll never have another experience like that.”

Chase insisted on shooting on location. It was HBO’s support for this expensive and unorthodox plan that convinced him, after a frustrating round of pitching to broadcast networks and an unsuccessful attempt to develop the series at Fox, that it was the right home for the show. The late ’90s were a good time for HBO, which Koblin says was “sitting on a pile of cash,” to take a big risk. Executives who never absorbed broadcast’s conservative norms gave Chase free reign. Even as budgets ballooned, HBO signed checks without saddling him with endless network notes. “Nobody told us to do anything,” Chase marvels. “We had complete creative freedom. It’s unheard of.”

Liberated from the imperative to supply the feel-good storylines advertisers demanded from broadcast programs, The Sopranos got to be dark, enigmatic, pessimistic. It wasn’t just a stylistic choice. Chase’s approach had profound political resonance. The show inhabited a world where, as Peter Biskind, the author of Pandora’s Box: How Guts, Guile, and Greed Upended TV, notes, morally complex antiheroes supplanted blandly heroic good guys and “the system was stacked in favor of the powerful against the powerless.”

This sense of peril has only gained currency—between 9/11 and the Iraq War, the rise of Donald Trump, a pandemic, and the growing existential threat posed by climate change. The Sopranos’ finale, which closes with the family gathering at Holsten’s diner when a man who may intend to assassinate Tony walks in, was notoriously divisive. In retrospect, though, it was a bridge to a contemporary reality permeated by foreboding. We couldn’t know what would happen once the screen went black for an excruciating eight seconds before the end credits finally rolled, the way we can never be certain what the future will hold. But all signs pointed to doom.

In a better world than The Sopranos depicted—maybe the world of Aaron Sorkin’s idealistic White House fantasy The West Wing, which also premiered in 1999 but now feels ancient—Americans might have banded together to beat back the encroaching darkness. Instead, society fragmented along lines drawn in the cataclysmic ’60s. TV responded, in large part, by cranking out safe, apolitical programming designed to soothe, rather than challenge.

Hence the rise of what has come to be known as comfort TV—the Ted Lassos, Great British Baking Shows, Schitt’s Creeks, and Emily in Parises that have become some of the most popular shows on TV. Chase is keenly aware of this shift: “I’ve been told, or it has been implied, that there’s a lack of interest,” among those who hold the purse strings in Hollywood, “in psychology, ambiguity, spirituality.” In other words: all the qualities that made The Sopranos what it was.

Because television has always been a business first and an art form second, there is, of course, a financial impetus behind this trend. The streaming wars escalated in the late 2010s, as studios like Disney and HBO’s parent company WarnerMedia (now Warner Bros. Discovery) launched proprietary platforms and scrambled to compete with Netflix, which had already spent years and billions to build an enormous library of originals. “The result of the competition among

the streamers is a stampede to get the biggest audience,” says Biskind. “And the way you get the biggest audience is to be the most bland because you don’t want to offend anybody.”

Now, with most streamers deep in the red and after months of production shutdowns amid a striking Hollywood, this competition for eyeballs has become more desperate than ever. According to Koblin, “There is certainly a threat that TV is about to look like the old days of television, before The Sopranos.” Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos recently predicted, he notes, that after subscribers flocked to the generic USA procedural Suits when it appeared on the platform last summer, “next year you’ll probably see a bunch of lawyer shows.”

An industry-wide return to network-TV norms wouldn’t just mean fewer, blander, and cheaper series. It could also endanger an auteurist movement in the medium, led by Chase, that has made creators as different as Vince Gilligan, Taylor Sheridan, and Michaela Coel household names. Chase’s “singular vision” guided the making of The Sopranos, Falco recalls. “I’ve worked on network stuff since then, and it really is incredible. Everybody wants [to put in] their two cents. And then I thought: ‘Why don’t you guys go in there and make it, then? Or if you’re going to let this person make it, get out of the way.’”

Falco is also skeptical that The Sopranos could be made in an atmosphere as concerned with what she calls “appropriateness” as Hollywood is today. She doubts that, for example, the show’s many layered, sometimes purposely disturbing sexual encounters would have felt as authentic had they been overseen by an intimacy coordinator. Choreograph a scene too tightly, and “you’re leaving out the possibility of last-minuteness.”

If it were to premiere amid our current, increasingly inflammatory discourse around identity and representation, The Sopranos might well see even more pushback than it faced upon release, when some mouthpieces for the Italian American community protested that it promoted harmful stereotypes and some feminists called its violence against women misogynistic. These arguments were always somewhat flimsy. The show didn’t relish women’s suffering any more than men’s. Despite Difficult Men author Brett Martin’s insistence that The Sopranos and its descendants were “largely about manhood,” female characters—resilient Carmela, idealistic Meadow, perceptive Melfi—had as much depth as their male counterparts. “If [these critics] watched and thought that women were incidental or second place?” Chase says now. “That’s pathetic.”

As for the Italian stereotypes, Chase recalls a meeting at the Beverly Hills Hotel, before The Sopranos premiered, with “four leading lights of the Italian American anti-defamation movement.” They had been sent advance tapes and complained that viewers would infer “that all Italians are criminals.” But when Chase tried to talk through individual scenes, they confessed that they’d yet to actually watch the tapes. “At that point I went, to myself: ‘F-ck. You.’ And that’s what I stuck with for the next six or seven years.” In this era of Notes app apologies and hair-trigger cancellations, it’s hard to imagine controversy-averse TV execs supporting such a combative stance.

Tony Soprano was a terminal nostalgist, always decrying the entitlement of a younger generation of wiseguys. “Whatever happened to Gary Cooper?” became his refrain. Now, The Sopranos is itself an object of nostalgia. Yet the show has recently found a new audience, particularly during COVID-19 lockdown—a cohort of viewers who weren’t necessarily alive, and definitely weren’t watching, when it premiered has been experiencing the show in the present tense. The designer Rachel Antonoff sells a trendy $295 jumpsuit depicting vignettes from the show. A clip of costumed 20-somethings at a “Sopranos Party” has more than 50,000 likes on TikTok.

Chase is heartened to see this generation—one known, perhaps unfairly, for over-policing the “appropriateness” of entertainment—embrace the show, though it also surprises him. “I always did wonder, what are they seeing in it?” Could the Y2K-retro costumes and red-sauce family dinners now constitute comfort viewing—like Friends, except sometimes the Central Perk crew starts killing each other? But ultimately, Chase suspects that young people, coming of age amid ever-intensifying fears for their future, “get the joke” about how America has become too corrupt even for a Mafia boss. He can imagine that “Gen Z people are looking at [The Sopranos] and saying… ‘I feel a connection to what’s being said here.’” Like Nirvana at the dawn of the ’90s shouting down the debauched fantasies of ’80s hair metal with wounded punk, the show inspires youthful passion because it dares to be blunt about the ugliest aspects of humanity.

Maybe the fight to make TV premised on discomfort has become an uphill battle, but our appetite for pessimistic realism persists. Two of HBO’s best and buzziest dramas of the past five years, Succession and The White Lotus, have taken dim views of America’s pampered capitalist class during a period of extreme economic polarization. And the more acerbic they got, the more audiences obsessed. But unlike The Sopranos, The White Lotus—an auteur project from writer-director Mike White—came out of HBO’s need to make a cheap, single-location series during lockdown. And, as Koblin and Gillette recount, Succession was, in part, the product of HBO head Casey Bloys’ search for a “vicious HBO spin” on NBC’s histrionic This Is Us. To the extent that viewers can still opt for challenge over comfort, much credit is due to long-serving creative executives like Bloys and FX’s John Landgraf, who Koblin says remain “incredibly important because their track records speak for themselves”—even if Bloys is now also overseeing a fluffier slate for Max, which last year unveiled What Am I Eating? With Zooey Deschanel.

Another small sign of hope for television as an art form in the post-Peak TV era? Chase and co-creator Hannah Fidell currently have a series in the works at FX, which aired Fidell’s provocative statutory rape drama A Teacher. “We’ve already been told that the audience isn’t going to sit still as long as they used to, waiting for something to develop,” Chase says. “They’ve got to see it right away in the pilot.” He senses industry angst about “elitism”—a charge you could only level against The Sopranos if what you meant was that it required independent thought on the part of its audience.

But so far, the network has been supportive. “No one has dropped an economic hammer on us yet,” says Chase. And then, before the conversation can get too upbeat, he adds: “But I fully expect it.