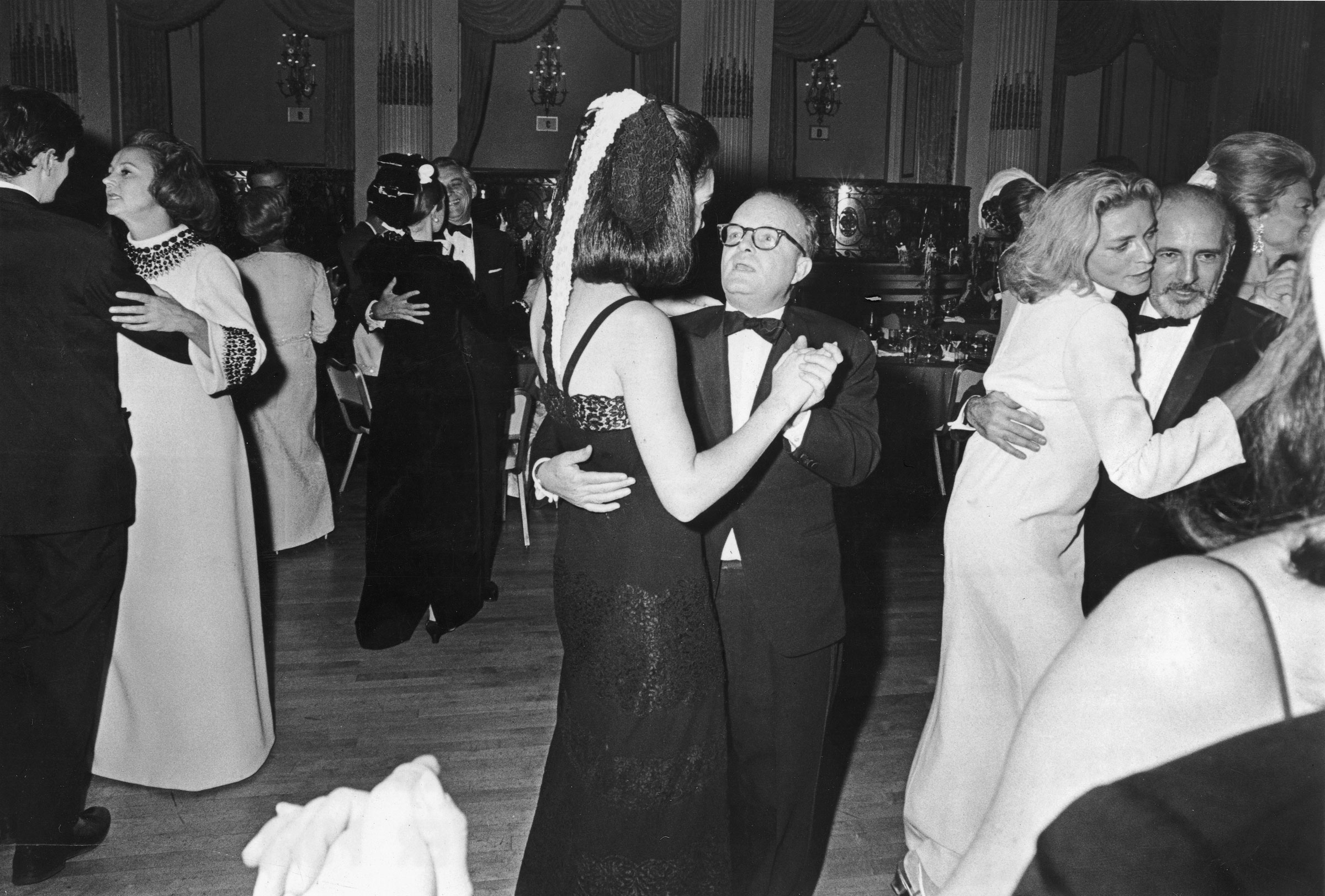

The third episode of Feud: Capote vs. the Swans centers on Truman Capote‘s famed Black and White Ball, a glittering social event that’s still referred to as “the party of the century.” The masked ball, which took place at the Plaza Hotel on Nov. 28, 1966, was not only the most glamorous (and coveted) invite of the year, but an affirmation of Capote’s celebrity and ascension to the highest echelons of New York’s high society, following the publication of his magnum opus, In Cold Blood.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Feud‘s interpretation of the ball is depicted through imaginary black and white footage shot by documentary trailblazers the Maysles brothers, for a possible film about Capote’s life and times. (In real life, the Maysles did shoot a short doc about him in 1966, titled With Love from Truman.) The verité framing gives ample opportunity for director Gus Van Sant to imagine the intimate moments and complicated dynamics of not only the elegant soirée, but the emotionally charged planning sessions and lunches Capote has with his beloved swans leading up to the event.

Read more: A Guide to the Real-Life Scandals and Socialites in Feud: Capote vs. The Swans

In real life, the Black and White Ball was not only extravagant, but culturally significant. The party was emblematic of the rapidly shifting culture of the ’60s, with a 540-person guest list that ran the gamut from European aristocracy, American politicians and New York socialites to artists, actors, writers, and a number of laypeople who tickled Capote’s fancy. According to Gay Talese’s oral history of the ball for Esquire, Capote kept a black and white composition book with a running list of potential guests for months leading up to the event.

Balancing high and low

The star-studded ball, which drew its theme from Capote’s affinity for the black and white “Ascot Gavotte” scene in the 1956 film My Fair Lady, was a study in the art of balancing high and low. Case in point: The ball was held in the the Grand Ballroom of the Plaza, an opulent venue secured by the commercial success of In Cold Blood (the affair cost him $16,000 total in 1966, about $150,000 in 2024). But Capote opted to serve a simple supper of chicken hash and spaghetti for the midnight meal—alongside hundreds of bottles of Taittinger Champagne.

His guests also embodied both this high-low ethos. In addition to swans like Babe Paley and C.Z. Guest, Kennedys, Vanderbilts and Rockefellers mingled with Hollywood stars like Lauren Bacall and Henry Fonda, Frank Sinatra and Mia Farrow. Among the invitees who were special to Capote but not a part of high society were his building’s doorman, one of his former schoolteachers, and the widow of the judge who presided over the trial in In Cold Blood.

In many ways, the ball was both a swan song for high society’s way of life and the figures that presided over it and a harbinger of how influence and power might be measured in the future.

“It was a marvelous party because there was such a mixture of people, all kinds, all ages,” said the jeweler Kenneth Jay Lane in a 2016 interview with the New York Times. “In the old days, it wasn’t a publicist society, and now it’s all publicists. People then had publicists to keep their names out of the papers, and nobody’d ever been to Kardashia.”

“There will never be another first time that somebody like Andy Warhol could step into a room with somebody like Babe Paley,” said Deborah Davis, the author of the 2006 book Party of the Century: The Fabulous Story of Truman Capote and the Black and White Ball, in an interview with the Times.

Attendees and a guest of honor

In the Feud episode, Capote’s party planning and canny deliberation of who should be his “guest of honor” both titillate and exasperate his swans, who all vie for his attention as he dangles this prize—though unbeknownst to them, he had already bestowed the honor on Katherine “Kay” Graham, the publisher of the Washington Post.

In reality, Capote had planned the party for Graham, even though many believe it was an excuse for him to throw a fantastic party for himself. Graham’s husband, Phil Graham, the former owner of the Washington Post, had died by suicide three years earlier, leaving Kay as his successor.

“Truman called me up that summer and said, ‘I think you need cheering up,’ Graham said in the Esquire oral history. “‘And I’m going to give you a ball’…I felt a little bit that Truman was going to give the ball anyway and that I was part of the props. Perhaps ‘prop’ is unfair, but I felt that he needed a guest of honor and with a lot of imagination he figured out me.”

Capote’s keen understanding of celebrity outside of just the discreet ranks of high society foreshadowed the tenets of modern celebrity. His party may have had an exclusive guest list that led to high-profile figures clamoring for an invite, but its lore was readily accessible, largely thanks to his own proselytizing. Outside of the event, nearly 200 photographers assembled to take photos of the guests as they arrived at the Plaza, with fans and onlookers watching from behind police barricades. The media inside, however, was limited to just four journalists, making actual coverage fairly exclusive (and insulating the event and its attendees from overexposure or critique).

The selectiveness of the journalists inside did little to dampen buzz about the event. Following the ball, the Times published the full guest list (an honor normally reserved for White House state dinners), while Women’s Wear Daily ranked the attendees’ looks (Gloria Guinness and Marella Agnelli were named best dressed, while Norman Mailer was named worst.)

Guests were required to wear black and white attire, as well as masks, which were removed at midnight. While some commissioned lavish masks from Halston, then a milliner at Bergdorf Goodman, and the Cuban designer Adolfo, Capote secured his own mask for 39 cents at the toy store FAO Schwarz.

Zac Posen’s reimagined gowns

For the episode, Van Sant and Ryan Murphy tapped fashion designer Zac Posen to design the magnificent gowns of Capote’s swans, as well as the gown worn by Kay Graham. The assignment was fitting; Posen, who was recently named the creative director of Gap, built his legacy as a designer on reinterpreting ball gowns for the modern woman and the red carpet, a sensibility that was indelibly influenced by the style icons that Capote counted among his swans.

“They were really the pinnacle of a period of real glamour,” he told TIME, noting that part of the swans’ allure was their true originality. “This is before the internet. This is before kind of red carpets. They were in a moment when they dressed for themselves—these were the ladies that set style and changed fashion, where a larger world looked to them as as the height of fashion at the moment, each in their own individual way.”

To prepare for the task of outfitting the characters of Babe Paley (Naomi Watts), C.Z. Guest (Chloe Sevigny), Slim Keith (Diane Lane), Lee Radziwell (Calista Flockhart) and more for the Feud ball, Posen spent hours researching, from poring over photos and film recordings of the entrances at the actual ball to sourcing the fabrics for the original dresses, and, later, diving into the biographies of each woman. When it came to creating the actual costumes, he drew on their backstories to generate similar looks to their real-life gowns, but reinterpreted for a modern audience.

For Posen, while the episode is a glimpse into a fantastic party, it’s also a testament to just how influential women like Paley, Guest, Keith, and Radziwell were to the development of the American fashion industry.

“These ladies are part of the foundation of style,” he says. “They changed how people dressed because they were the people that supported the designers, the early foundation of American style. They really paved the way for American taste and style to form and have definitely influenced history.”

For Posen, the episode also embodies why Capote’s Black and White Ball has remained such a cultural touchpoint, nearly 60 years after it took place.

“The Black and White Ball is so significant because it was a real cultural changing moment, when the old world at its height met the contemporary world that we know today,” he says. “This was our moment of American royalty—so much changed after.”