Over more than four decades, Bangladesh’s Grameen Bank has disbursed some $37 billion in collateral-free loans to over 10 million of the world’s poorest people. But founder Muhammad Yunus still remembers the first $5 he ever lent.

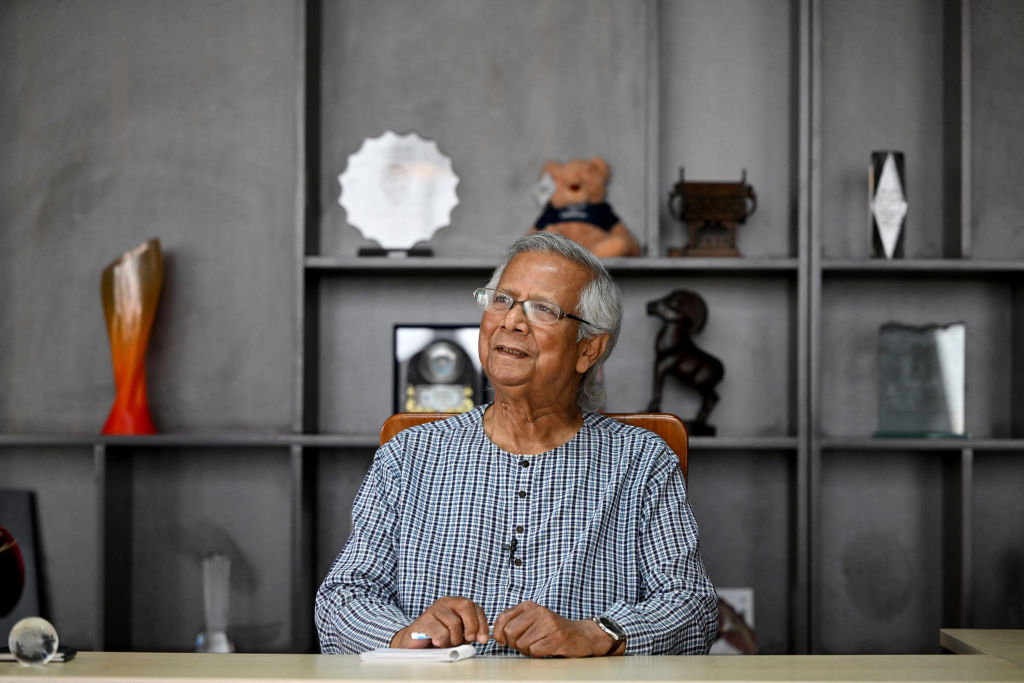

It was 1974 and Yunus had recently returned from a teaching position at Middle Tennessee State University to his native Bangladesh, which three years earlier had won independence from Pakistan in a blood-soaked civil war. Yunus was determined to contribute to the fledgling nation’s development and took a post as head of economics at Chittagong University, though quickly became disillusioned with academia given the rampant poverty he encountered daily amid a brutal famine. “Economics is a meaningless subject,” he thought, Yunus, now 83, recalls in a Zoom interview with TIME. “These are empty ideas, which have not taught me how to help poor people protect themselves from hunger.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Yunus wandered the mud lanes of the villages near his campus looking for practical solutions. At one, he spied a woman making elegant bamboo stools outside a tumbledown shack. “I saw there’s a complete difference between the stools she’s making and the house she lives in,” Yunus recalls. The woman was initially hesitant to speak to Yunus, abiding by traditional Islamic mores, though he eventually coaxed out of her that the materials she needed cost the equivalent of $5, which she secured from a loan shark. But instead of then selling her stools on the open market, the loan’s terms obliged her to sell her entire inventory to the lender at whatever price he dictated.

“I said, ‘this is slavery, this is not a business!’” Yunus recalls. “For the sake of $5 someone with such beautiful skills can be turned into a slave.”

Yunus decided to lend the woman the $5 under the loose understanding that she should repay him whenever she was able. He also encouraged her to tell other villagers in a similar predicament to come to him, eventually lending $27 to a group of 42 women. Out of that simple act was spawned a “microcredit” research project whose success became Grameen (Village) Bank in 1983.

The microcredit phenomenon Yunus started has since mushroomed to over 100 developing countries across the globe and even developed countries like the U.S. Since opening its first office in New York’s Jackson Heights in 2008, Grameen has spread to 35 American cities and lent over $4 billion to predominantly minority women. It managed $1 billion in loan disbursement last year alone with repayment rates consistently above 99%. Overall, more than 94% of Grameen loans worldwide have gone to women, who suffer disproportionately from poverty and are more likely to use earnings to help their families than men.

It’s a life’s work fighting poverty that has won Yunus the sobriquet “banker to the poor” and no shortage of plaudits, including the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize, the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009, and the Congressional Gold Medal a year later.

Yet today Yunus is a common criminal, more likely to be seen literally caged inside a Dhaka courtroom than strolling the White House Rose Garden as in his pomp. In January, Yunus and three other officials at his telecommunications company, Grameen Telecom, were sentenced to six months in prison for violating Bangladesh’s labor laws. They were immediately bailed pending appeal, though it’s just one of over 200 cases—including forgery, money laundering, and embezzlement—Yunus faces as the increasingly autocratic government of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina pursues despite widespread condemnation a bitter and bizarre vendetta against him.

Last August, more than 170 global luminaries—including former U.S. President Barack Obama, former U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, and more than 100 Nobel laureates—penned an open letter urging Hasina to end the “continuous judicial harassment” against Yunus. In June, U.S. State Department spokesman Matthew Miller expressed “concern that these cases may represent a misuse of Bangladesh’s labor laws to harass and intimidate Dr. Yunus.” Amnesty International deems his treatment “emblematic of the beleaguered state of human rights in Bangladesh, where the authorities have eroded freedoms and bulldozed critics into submission.”

Yet nothing quells the fury of Hasina, who since 2011 has derided Yunus as a “bloodsucker” of the poor, forcing him out of Grameen Bank that same year. What lies behind her crusade against Bangladesh’s most famous son is “the trillion-dollar question,” says Yunus. “Nobody can really answer; it doesn’t make sense to anyone. But it goes on.”

The truth is complex, melding personal jealousy, a precipitous decline of democracy and human-rights inside Bangladesh, as well as waning American influence across a region suffering a distinct authoritarian revival. First, it’s an open secret that Hasina is consumed with jealousy that Yunus won the Nobel Peace Prize given her repeated snubs. She deeply covets the award, which she first believed she was owed for negotiating the 1997 Chittagong Hill Tracts Peace Accord, and then also for taking in over a million Rohingya Muslim refugees who fled pogroms in neighboring Myanmar in 2017. In Bangladesh, editorials and government bigwigs regularly bemoan her lack of recognition by Norway’s Nobel Committee.

Another key factor is that Hasina sees Yunus as a political rival. In January 2007, Bangladesh’s military seized power and offered to make Yunus caretaker Prime Minister. He declined but that February launched a political party ostensibly to tackle the corruption and vicious polarization that had paralyzed governance. The gambit only lasted 10 weeks as whatever political backing Yunus believed he had evaporated, and he has since repeatedly disavowed any political ambitions. Hasina “continues to accuse me of getting into politics,” says Yunus, “as if getting into politics is a crime.” Hasina—who was in military detention when Yunus launched his brief political dalliance—has never forgiven what she perceives as a gross betrayal. “Sheikh Hasina took it very badly that he was seen as a political alternative,” says Meenakshi Ganguly, Asia deputy director for Human Rights Watch. “That really is still what seems to be driving this campaign to discredit him, jail him, humiliate him.”

Ever since, whenever something goes awry, particularly involving Western dignitaries or institutions, Hasina points the finger at Yunus. In 2012, the World Bank reneged on funding construction of the Padma Bridge—Bangladesh’s longest bridge, connecting the less developed southwest of the country to the capital Dhaka and the north—citing “credible evidence corroborated by a variety of sources which points to a high-level corruption conspiracy.” (The project was eventually completed in June 2022 with state funds.) Hasina has repeatedly accused Yunus of using his elite connections to torpedo the World Bank loan in revenge for being forced out of Grameen—an accusation he denies—telling a meeting of her Awami League party in May 2022 that Yunus “should be plunged into the Padma River twice. He should be just plunged in a bit and pulled out so he doesn’t die, and then pulled up onto the bridge. That perhaps will teach him a lesson.”

No opportunity to attack Yunus is missed. In April 2012, he signed a joint statement alongside three other Nobel laureates criticizing the prosecution of gay people in Uganda. Over a year later, the statement was picked up by Bangladesh’s state-run Islamic Foundation, which organized mass rallies denouncing Yunus as an “apostate for supporting homosexuality,” amplifying the condemnation via the tens of thousands of Imams on its books. “They accuse me of being a ‘usurer,’” says Yunus with a weary sigh. “That’s one of the worst things a Muslim can do, taking interest from poor people.”

It hasn’t helped that the concept of microcredit has become tainted in recent years. As with any runaway success story, unscrupulous operators quickly emerged that leveraged the branding “microcredit” as a figleaf for traditional for-profit lending services, leading to a raft of botched schemes and negative coverage. Yunus has long railed against for-profit schemes, writing criticisms of so-called “microcredit” banks that have floated on the stock market. “To IPO is all about telling people you can make lots of money by helping poor people,” says Yunus. “That’s loan-sharking microcredit.”

Today, Hasina is one of microcredit’s most outspoken critics. Yet it was not always the case. In early 1997, less than a year after she became Prime Minister for the first time, Yunus organized a Microcredit Summit in Washington D.C., with Hasina as co-chair. During her welcome speech, Hasina lauded the work of Yunus and called for expanding microcredit as “a critical next step in the effort to reduce and eradicate overall poverty from the face of the Earth.”

An entente seemed completely natural. Yunus was a staunch supporter of Hasina’s father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Bangladesh’s liberation hero and first President. While teaching in Tennessee, Yunus founded a citizen’s committee, ran the Bangladesh Information Center and published a newsletter to raise awareness of Bangladesh’s liberation struggle. Asked what Sheikh Mujibur would make of his daughter’s vendetta, “I’m sure he would be upset,” Yunus says, “he would not know what this is all about.”

Certainly, Hasina’s political travails over recent decades—including military interventions, over a dozen assassination attempts, and regular bouts of political bloodletting—have hardened her, imparting a tremendous sense of personal grievance. Over the last 15 years of her rule, she has co-opted nearly all instruments of the state, most noticeably the judiciary. Last September, Bangladesh Deputy Attorney General Imran Ahmed Bhuiyan publically declared that cases against Yunus amounted to “judicial harassment.” He was dismissed from his position within days and briefly went into hiding with his family at Dhaka’s U.S. Embassy following threats to his life.

Bangladesh’s deteriorating relationship with Washington also likely contributes to Yunus’s predicament. As by far the most famous Bangladeshi internationally, who says he counts former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton as a “friend,” Yunus has become a lightning rod for an increasingly tense bilateral relationship. Amid a deteriorating human rights picture in Bangladesh, including millions of opposition activists facing politically motivated charges and almost 2,500 reported extrajudicial killings between 2009-2022, Hasina was not invited to the Biden Administration’s latest two Summit for Democracy gatherings. In May last year, Washington unveiled visa restrictions on any Bangladeshi undermining January’s general election. In response, Hasina told parliament the U.S. was “trying to eliminate democracy” by engineering her ouster.

Hasina did not flinch under American pressure and was returned to power in a ballot boycotted by the opposition and denounced by the U.S. as neither free nor fair. Yet the fresh mandate has emboldened Hasina. The perception amongst Dhaka’s governing elite of Yunus as an American stooge wasn’t helped by Wikileaks cables detailing his frequent and candid meetings with top American diplomats to bemoan the sorry state of Bangladeshi politics. There’s a sense that whenever the U.S. imposes a cost on Hasina, Yunus serves as a convenient whipping boy.

Others feel that, to some degree, Yunus has made his own bed. Despite mounting human-rights abuses and leeching democratic freedoms, Yunus has stayed silent, refusing to publicly condemn Hasina or speak out. If his apparent acquiescence was designed to mollify Hasina, he misjudged the depths of her grievance. And while Hasina’s fury remains unsated, Yunus’s silence did not endear him to the beleaguered opposition. Today, Yunus has few champions inside Bangladesh and his friends overseas have waning influence. When, in 2018, outspoken Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam was thrown in jail following criticism of the government, the public opprobrium was so ferocious that authorities felt pressured to release him on bail after 107 days. By comparison, the reaction to Yunus’s plight is “maybe 5-10%,” says Mubashar Hasan, a Bangladeshi scholar at the University of Oslo, Norway. “It’s not even noticeable. Nobody except a few journalists and civil society actors are actually behind him. He lost touch with the people of Bangladesh.”

Hasan, who himself suffered 44 days extrajudicial detention in a secret military jail in 2017, says that Yunus could have used his unparalleled global profile to shed light on Bangladesh’s deteriorating rights situation. However, it was only after January’s court verdict against him that he chose to speak out. “He thought that his influential connections would serve as protection,” says Hasan. “He miscalculated. The regime has gotten so much confidence with the support of India, China, and Russia. Yunus’s perception of himself as untouchable backfired.”

For Yunus, he was merely keeping his word that he would stay out of politics, though today he sees his fate inexorably entwined with compatriots he spent a lifetime helping. Despite a deluge of offers of comfortable positions overseas, he’s determined to stay in Bangladesh to clear his name—even if that means jail. “If that’s the fate that is waiting for me,” he shrugs, “I cannot run away from the country just because I want to avoid a prison sentence. Because it’s not just me as a person, it is my lifetime’s work. The moment I decide to leave, all these things will be torn apart.”