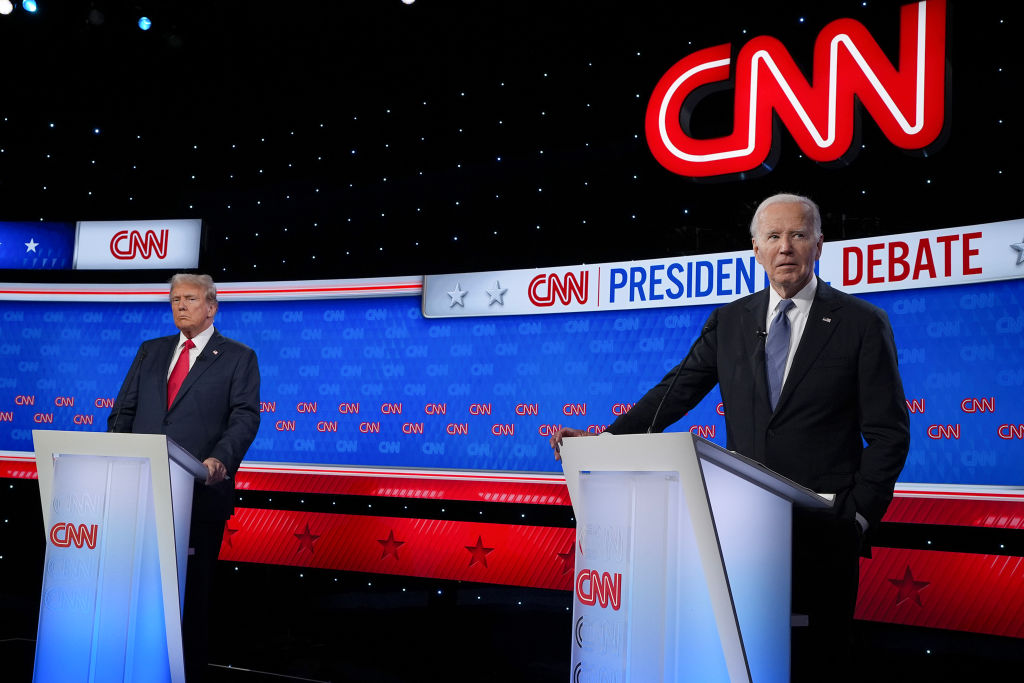

America’s political gerontocracy is hard to avoid noticing. Our presidency continues to be dominated by septuagenarians and octogenarians, and Mitch McConnell will finally retire from running the Senate at age 82. The Dianne Feinstein revelations of advanced dementia mere months before her death at 90 years of age vividly demonstrated the potential ramifications that come with a consolidated elderly leadership. WWFD: What would the Founders Do?

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

The Founders did care about the implications of an increasingly gerontocratic government and sought to avoid it. In their own lifetimes, they moved from a monarchical political system that prized the wisdom of age—and therefore often allowed political figures who were far past their prime—to a democratic system where voters intentionally placed political offices of trust in vigorous middle-aged men. To them, political leadership demanded cognitive and emotional quickness and flexibility.

Read More: The Weaponization of Biden’s Age

In the colonial period, governors had often drawn from the older set. In part, that was because it was considered a more ceremonial role. The European system of governance was based on the extreme hierarchal assumptions of monarchy. In practice, Europeans had long experience with deficient, and even doddering, senile monarchs. They had also come to rely on the de facto separation of ceremonial power awarded by birth and position from the real power wielded in part by courtiers and advisors. The American colonial system re-created many of the more aristocratic features of government, such as governorships that were advised by an appointed council. Elderly leaders were acceptable in these roles so long as their power was circumscribed. For example, Jonathan Trumbull of Connecticut served as governor until he was 74 years old.

After the Revolution, voters saw governors as democratic leaders of thriving representative governments. Leaders were no longer ceremonial, but executives charged with military leadership, political planning, and financial acumen. Governors started getting younger. Stevens T. Mason, the first governor of Michigan, was the youngest of all at 24 years old. Lots of governors were elected in their early 40s, such as Isaac Tichenor and Richard Skinner of Vermont and James Monroe of Virginia. There were positively youthful governors such as 33-year-old Edmund Randolph of Virginia; 37-year-old John Rutledge, wartime governor of South Carolina; and 34-year-old John Drayton of South Carolina. Even Connecticut, long the preserve of septuagenarian governors, finally started electing men in their 40s by the 1810s.

There were similar expectations for the presidency. All but one of the first eight presidents of the United States were elected in their 50s, with only John Adams stretching the boundaries of middle age at 60. Voters knew that life expectancy for people who made it to adulthood would take them into their 70s, well past their term in office.

Read More: Congress Needs to Rethink Its Obsession With Longevity. The Reaction to Dianne Feinstein Won’t Help

Younger men looked forward to holding office as well as rising in business at ever younger ages. Gouverneur Morris, a signer of the Constitution, put his finger on the changes in the air when he wrote that “although some of the present generation may feel colonial Oppositions of opinion, that generation will die away, and give place to a race of Americans.” A new generation saw themselves as the people ready to embrace the freeing possibilities of democracy and freedom. They moved out of their parents’ homes younger, started their own families younger, set out in new occupations, and forged a vibrant new, pervasive media environment predicated on the liberatory possibilities of partisan politics in bringing ordinary people into the conversation.

The Founding generation also worried that older men were more inflexible, obstinate, uninterested in change, and stuck in their ways—all leadership qualities at odds with the experimentation needed for representative government. They wanted leaders who embraced flexibility and change in shaping what a thriving democracy could look like. When Benjamin Franklin Bache, the tempestuous grandson of Benjamin Franklin, wanted to attack President John Adams, he inveighed against his old age as a shorthand for an old generational aping of monarchal arrangements. Abigail Adams complained that Bache “in his paper calls the President old, querulous, Bald, blind, cripled, Toothless Adams.”

Most of all, the Founders shared a new-found fear that all older people might suffer from cognitive decline and outright dementia. In a democracy, elected leaders hold real power. It was essential to make sure they were mentally competent to wield that power on behalf of the people.

Thomas Jefferson repeatedly invoked his wariness of his own mental decline late in life: “Eighty two years old, my memory gone, my mind close following it.” In fact, he was still sharp as a tack, but he and his aging friends looked out for signs of cognitive decline in each other. It was a frequent topic of gossip when older men wrote to each other. Samuel Adams ruefully admitted he “cannot help feeling that the powers of his mind as well as his body are weakened, but he relies upon his memory, and fondly wishing his young Friends to think he can instruct them by his Experience, when in all probability, he has forgot every trace of it, that was worth his memory.” They understood that people suffering mental decline were poor judges of their own changing abilities.

Indeed, assertions of mental decline became political ammunition. When Jefferson went on the attack against President Washington, he funneled allegations that Washington was increasingly senile to his favorite newspaper, which published these attacks repeatedly. Washington found the rise in such partisan attacks infuriating—especially since the charges stuck. He had admitted to his own concerns about his slowing mental quickness to both Jefferson and James Madison when he explained why he wanted to retire after one term.

So if the Founders worried about the likelihood of political leaders of advanced age losing their marbles while in office, why did they not enact guardrails in the Constitution? At the constitutional convention, the Founders wrote in minimum age requirements for federal office, but rejected constitutional maximum age requirements because they believed in the discernment of the electorate. They were overly optimistic about our system’s ability to screen, counsel out, and if need be, defeat dementia-affected political leaders at the ballot box.

Read More: Believing Myths About Aging Makes Growing Old Worse

Initially, their belief in moral suasion worked. Washington and others monitored themselves and fellow leaders. The Electoral College system depended on the back-room conversations of men who were from the same communities and had manifold opportunities to engage in conversation and probe the mental fitness of men seeking high office. Local whisper networks could be amplified by the national press and a national networking circuit.

That’s why we are left without a clear constitutional solution. But that lack is not because the Founders did not see the problem, and it is not because they did not seek to rectify it.

As we mark another Fourth of July, perhaps it is time to return to the problem of aging leadership with more than the strategy the Founders left us with. Potential answers include ending the seniority system in the Senate, instituting required mental fitness and memory tests for political leadership, and amending the constitution to put maximum age requirements for federal office into place.

Rebecca Brannon is the author of From Revolution to Reunion: The Reintegration of the South Carolina Loyalists (University of South Carolina Press, 2016). The Road to 250 series is a collaboration between Made by History and Historians for 2026, a group of early Americanists devoted to shaping an accurate, inclusive, and just public memory of the American Founding for the upcoming 250th anniversary.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.