At the Paris Olympics this month, World Athletics — the governing body that oversees elite track-and-field sports — will be enforcing strict policies that block many trans and intersex women from competing in the women’s category. These policies date back to the 1930s, when World Athletics first passed a rule forcing athletes about whom there were “questions of a physical nature” to strip down before a doctor and “prove” their womanhood. These were cruel, unscientific procedures, but for decades, officials cited a single name as justification for them: Heinz Ratjen.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

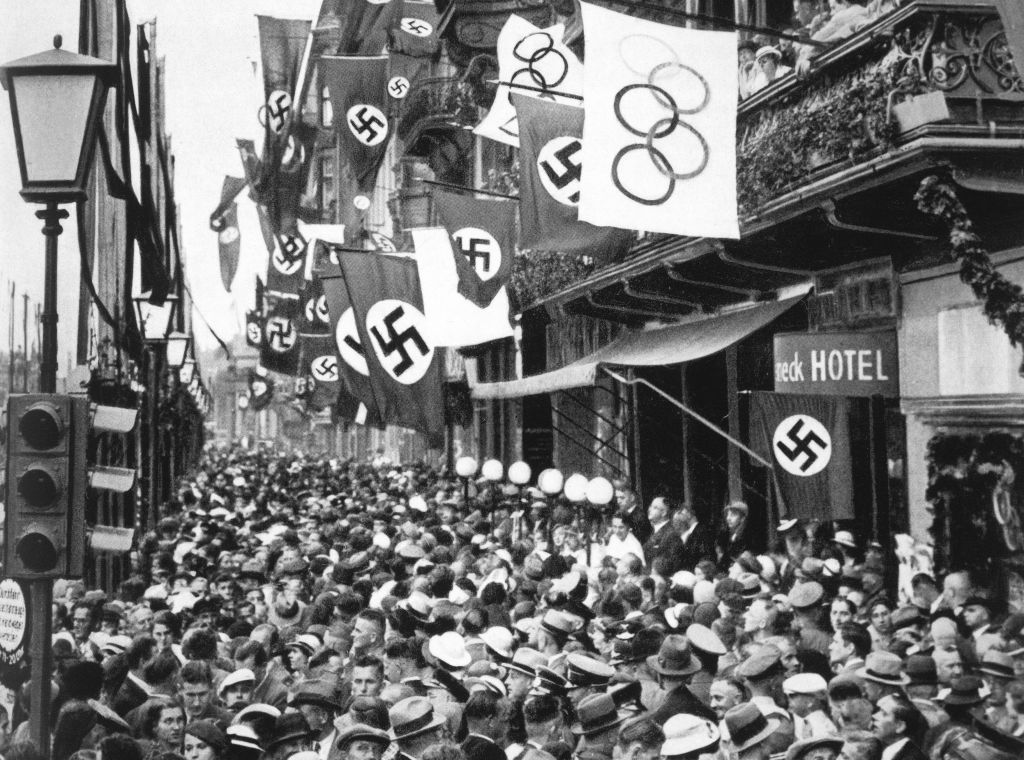

Ratjen, a German high jumper, competed in the Berlin Olympics in 1936, placing a disappointing sixth place in the women’s category. Two years later, he quietly dropped out of sports and began living as a man. Somewhere along the way, though, the story of his life got twisted. After World War II, news outlets began portraying Ratjen as an Olympic cheat — a cisgender man who, under the directive of the Nazis, dressed up and competed as a woman. Ratjen’s story began to serve as proof that gender fraud really had happened at the Olympics — justification for the efforts to strip test, chromosome test, and hormone test women who wanted to compete.

The myth of his life continues today. In 2008, the New York Times called Ratjen the “one known case of gender cheating” at the Olympics, given that the “Nazis had forced him to compete as a woman.” Today, History.com lists him as one of “9 cheaters in Olympic history.” So does Business Insider. Pundits like Andrew Sullivan still circulate the same story about Ratjen being a cis man in disguise. No one wants to see the real story. But by uncovering what really happened to Ratjen, we can see just how much sex testing policies in sports have been bound up in willful misinformation.

Read More: The Intersex Community Is Fighting for Every Body

Heinz Ratjen was born on Nov. 20, 1918, near the city of Bremen, Germany, to a father who owned a local hotel. He was assigned female at birth, and given a feminine name he would later reject. The world understood him as a girl, though Ratjen was secretly beginning to question his own gender. The Germany that Ratjen grew up in was at the forefront of providing healthcare for gender minorities, a status that the Nazis violently dismantled when they took power. But it’s unclear how much of this reached Ratjen, who grew up poor and far from Berlin.

In 1934, when Ratjen began entering high jump competitions in his home city, it was in the women’s competition. German officials quickly scouted him for their Olympic team. After placing a middling sixth in the high jump at the 1936 Olympics, Ratjen continued to compete in sports, and in September 1938, set a new world record, scoring 1.7 meters in the high jump at the European Championships in Vienna.

It all collapsed on the train ride home from Vienna. At a stop in Magdeburg, Germany, a pair of Nazi soldiers pulled him aside. They believed him to be a cis man who was dressing up as a woman in order to cross the border — potentially a British or French spy. They arrested him and brought him to the police station, where they took his mug shot and put him through an invasive medical exam. A police doctor wrote after examining Ratjen that “this person is indisputably to be regarded as a man,” according to historian Victor Kluge.

Under the directive of the Nazis, Ratjen took the name Heinz — short for his father’s name, Heinrich — and received new government documents identifying him as a man. Ratjen, who would probably fit a contemporary definition of intersex, did seem to want to live as a man, telling police that he was “happy” now that “everything is out in the open.”

But the pressure the Nazis put on him must have been immense. He didn’t have much room to say no to the brownshirts even if he had wanted to. The Nazis regularly persecuted and killed people who challenged their gender and sexual norms. That, in this case, they had validated Ratjen’s own desire to live as a man probably did not occur to these officials; certifying him as a man seemed like the easiest way to sweep the entire controversy under the rug.

Rather than the masterminds of a conspiracy to gain an advantage in sport, the Nazis were mortified to discover that Ratjen was intersex. They allowed only one article about Ratjen to appear in print, in the sports magazine Der Leichtathlet in 1938. “As a result of a medical examination,” Der Leichtathlet wrote cryptically, “it has been established that [Heinz] Ratjen cannot be admitted to female competitions.” Days later, on Oct. 12, the Reich Propaganda Ministry demanded that “nothing further” be published about Ratjen in Germany. A high-ranking Nazi SS officer, Reinhard Heydrich, expressed his gratitude that “the Ratjen case has not led to undesirable discussions in the public sphere or even to conflicts in international sport.”

The Nazis didn’t let the story end there. Karl Ritter von Halt, a member of the International Olympic Committee and a registered member of the Nazi Party, decided it was time for sports to get more explicit about keeping intersex people out of sports. On Nov. 21, 1938, just a month after Ratjen’s arrest, von Halt suggested that World Athletics introduce a new policy requiring all women competitors to prove their sex. Von Halt thought that all “ladies taking part in the Games 1940 shall produce doctors’ certificates stating that they are women.”

A decade later, when the Olympics returned following the end of World War II, von Halt’s policies were in full force. In 1948, suddenly, women could only compete at the Olympics if they provided a note from their doctor “verifying” their sex. In other words, these policies—and the rigid notions of biological sex that animate them—come directly from Nazi officials.

Read More: Why Even Democrats Are Going Wobbly on Trans Rights in Sports

The Ratjen narrative began to change in July 1957, when the British tabloid The People published a bombshell report of gender fraud. Under the headline “He Was A Man All The Time,” the paper claimed to have the exclusive on Ratjen coming clean. “I never was a woman,” he reportedly said. “I was forced by the Nazis to pose as one.” According to the paper, Ratjen had been assigned male at birth and lived as a boy until a “high official” told Ratjen to “start living as a girl and try to win a jumping title for the sake of the honor and glory of Nazi Germany.” Ratjen committed to his new role as a girl in disguise. In anticipation of the Berlin Olympics in 1936, he let his hair grow, and he took feminizing “injections.”

It was a fantastical story of fraud, the perfect kind of Cold War tabloid story — a scandal involving gender, queerness, and a Nazi conspiracy. But there is “a probability bordering on certainty” that Ratjen did not actually give this interview, according to historian Victor Kluge. Few of the details in The People’s story square with archival evidence, and The People itself, while generally a reliable source, had a reputation for sensationalizing queerness, according to scholar Justin Bengry. One of its editors recalled that some reporters “regarded the truth as dispensable if he could improve a quote or a story and get away with it.”

But the fabricated story of Ratjen spread across the world anyway. Nine years later, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram referred to Ratjen as one of the first “gay deceivers” in sports, a myth that only gained steam over the decades. TIME itself, in the 1960s, repurposed quotes from The People, reporting that Ratjen had said, “For three years I lived the life of a girl. It was most dull.” In 1994, The Vancouver Sun repeated the claim that Ratjen “was forced by the Hitler Youth to pose as a woman for three years.”

Today, we are still getting Ratjen’s story twisted. By all accounts, Ratjen genuinely understood himself to be a woman — until he didn’t.

After 1938, Ratjen had little option but to live out a quiet life. In 1963, he inherited a pub from his father, and ran it for ten years. He died in April 2008, just a few months before the Beijing Olympics, when the New York Times again repeated the lie that he had cheated at the Olympics. Despite many requests, Ratjen never gave an interview about his life.

The false story that spread around the world continues to have power. Using Ratjen’s story, sports officials have framed the need for sex testing policies as a way to prevent bad actors like the Nazis from cheating.

Yet the truth is that Nazi officials were one of the driving forces behind these policies. These policies weren’t designed to stop the fascists. They were designed by the fascists.

Michael Waters is the author of the new history book The Other Olympians: Fascism, Queerness, and the Making of Modern Sports.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.