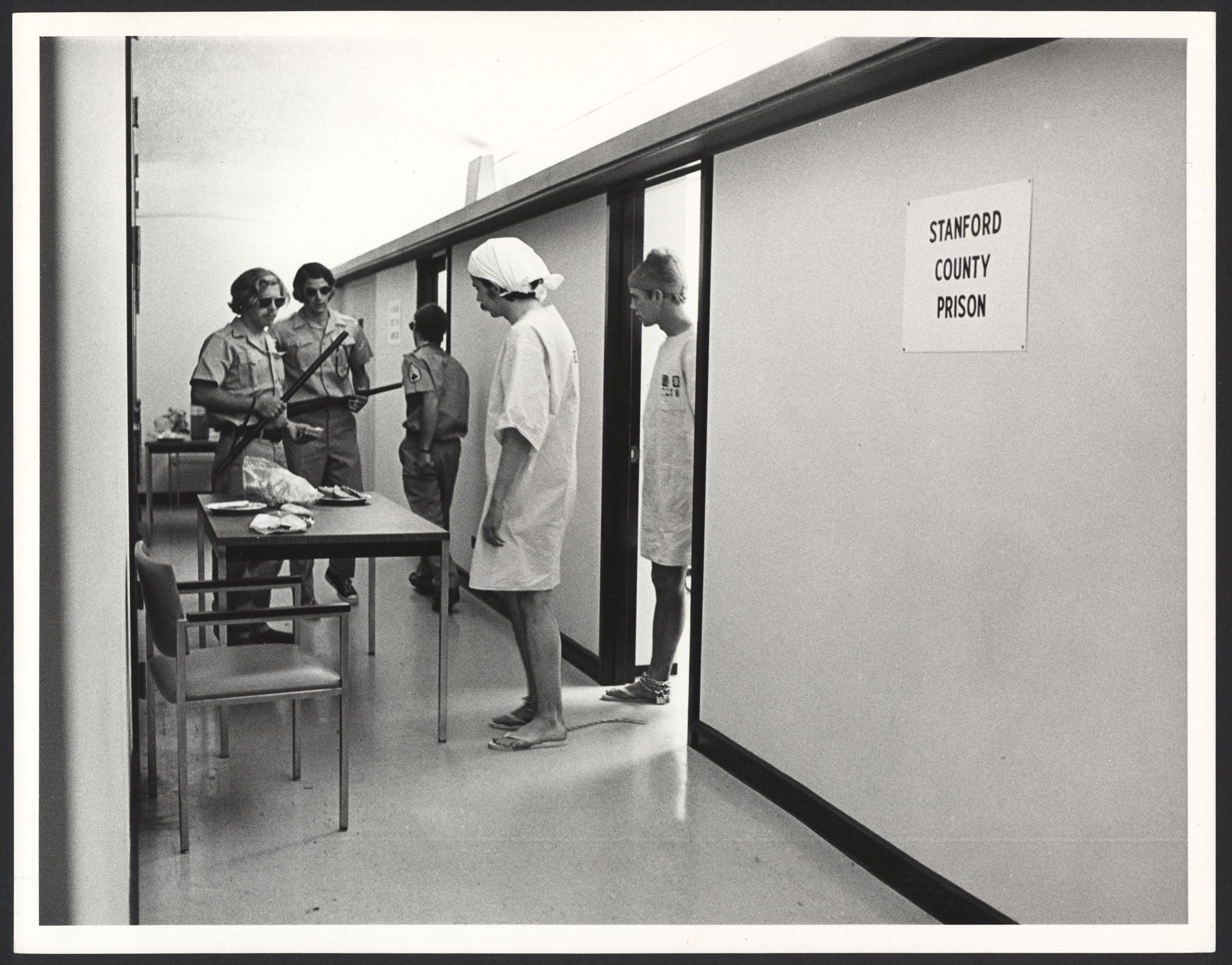

In August 1971, at the tail end of summer break, the Stanford psychology professor Philip Zimbardo recruited two dozen male college students for what was advertised as “a psychological study of prison life.” The basement of a university building was transformed into a makeshift prison. Some of the young men were assigned to be prisoners; the others became guards. The study turned dark almost immediately, as guards drunk on power mocked, humiliated, and cruelly punished their charges. Prisoners had breakdowns. Zimbardo had to shut down the study, which was supposed to run for two weeks, after just six days. While the experiment had been egregiously unethical, it did prove that circumstances have the power to make normal people act like tyrants—or what Zimbardo has called “the power of the situation.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

So goes the legend of the Stanford Prison Experiment, cemented over more than half a century with lots of help from pop culture. Rocketed to fame when the Attica prison uprising dominated headlines just weeks after his study concluded, the media-savvy Zimbardo (who died in October) spent much of his career promoting the theory that putting good people in bad situations makes them do bad things. Abu Ghraib was, for obvious reasons, another big moment for him. When the acclaimed indie film The Stanford Prison Experiment hit theaters in 2015, starring Billy Crudup as Zimbardo and a pre-Succession Nicholas Braun as a subject, it joined a global canon of movies that reinforced his read on what happened in that Stanford hallway. The problem, as director Juliette Eisner demonstrates in her riveting Nat Geo documentary series The Stanford Prison Experiment: Unlocking the Truth, is that Zimbardo’s account of the study was far from definitive. The conclusions he drew about our moral malleability may be more pop psychology than science.

Many of the short docuseries that proliferate on streaming play like features chopped into episodes for viewers who’d rather binge on TV than commit to a whole movie. But the three-part Unlocking the Truth, which premieres Nov. 13 (and will stream the following day on Hulu and Disney+), functions as a true triptych. Through new interviews with participants and clips of the so-called “Stanford County Prison,” the first episode provides a chronology of the experiment that is largely faithful to Zimbardo’s version. The second, titled “The Unraveling,” introduces Thibault Le Texier, a French researcher who has worked to debunk the experiment, and intersperses his insights with more participant interviews that complicate or outright contradict Zimbardo’s account. Twenty minutes into the episode—at what is roughly the midpoint of the series—onscreen text informs us that the prison clips we’ve been watching aren’t footage from the study but reenactments shot on a soundstage by Eisner’s team, as “only a fraction of the experiment was filmed in 1971.” The finale pairs one of Zimbardo’s last-ever interviews with scenes of the real participants visiting the soundstage, advising the actors who portray them on what really happened and talking amongst themselves about the experience and its legacy.

A long history of Stanford Prison Experiment dissent

Psychologists have been critiquing the Stanford Prison Experiment for as long as it’s been part of the discourse, though their points have mostly failed to penetrate the public consciousness. Erich Fromm picked apart Zimbardo’s methods in his 1973 book The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness, concluding that “the difference between the mock prisoners and real prisoners is so great that it is virtually impossible to draw analogies from observation of the former.”

In 2002, the BBC aired a program called The Experiment, which documented British psychologists Alex Haslam and Steve Reicher’s restaging of the Stanford study. With an onsite ethical committee and the experimenters observing rather than participating (Zimbardo had acted as SCP’s superintendent), the prisoners wound up banding together and using their solidarity to extract better conditions. Haslam and Reicher have also noted that Zimbardo might’ve influenced guards’ behavior by making suggestions like this direct quote from a pre-experiment training session: “You can create in the prisoners feelings of boredom, a sense of fear to some degree, you can create a notion of arbitrariness that their life is totally controlled by us, by the system, you, me… They can do nothing, say nothing, that we don’t permit.” (There is, of course, the possibility that the presence of TV cameras affected the outcome of Haslam and Reicher’s own experiment.)

Even the ad Zimbardo placed to recruit participants could have unwittingly influenced the behavior he observed. As Maria Konnikova described in a New Yorker essay that coincided with the 2015 film, psychologists Thomas Carnahan and Sam McFarland found, in 2007, that the presence of the words “prison life” in the ad likely narrowed the field of potential participants. When they ran their own experiment to see if they would receive different types of respondents by publishing the ad both as written and with the latter phrase omitted, Konnikova writes, they found that “those who thought that they would be participating in a prison study had significantly higher levels of aggressiveness, authoritarianism, Machiavellianism, narcissism, and social dominance, and they scored lower on measures of empathy and altruism.”

How Unlocking the Truth furthers the case against the Stanford Prison Experiment

Le Texier, who published his findings in an American Psychologist article and the book Investigating the Stanford Prison Experiment: History of a Lie, identified additional problems with the study by scrutinizing Zimbardo’s archives. In the series, he explains that not only did the professor hold a “Day 0” orientation for guards in which he encouraged them to make prisoners feel powerless; he also distributed documents to them including a list of rules and suggested daily schedule. Along with making choices for the guards that they were represented as having made on their own, Zimbardo’s extensive instructions made it unclear whether the guards should’ve seen themselves as subjects of the experiment or as confederates in running it.

But Le Texier is far from Eisner’s only source who breaks with Zimbardo. Doug Korpi, a prisoner who was sent home after what has been portrayed as an emotional breakdown, says he was really just acting out of frustration after discovering how tough it would be to get dismissed from what he viewed as a bad job. A guard named John Mark recalls the warden, a grad student of Zimbardo’s, taking him aside for a “pep talk” urging Mark to be tougher on inmates. Dave Eshleman, the notorious guard nicknamed “John Wayne” (not a compliment among college students of the era), has said before that he was an actor and saw the experiment as a role. Here, he also notes that he and other subjects perceived Zimbardo’s goal of indicting the carceral system, supported that aim, and thus behaved in a way that reflected that “we would’ve done anything to prove this prison system was an evil institution.” (Now, as Eisner shows us, the theatrical Eshleman plays in a British Invasion tribute band.)

Most remarkable, to my mind, is Eisner’s interview with a man, identified in Le Texier’s research, named Kent Cotter. “I’m the guy that you never heard about, that you should be hearing about,” he says. (Indeed, googling “Kent Cotter” with “Stanford Prison Experiment” before Unlocking the Truth’s premiere yielded zero English-language results.) “Because I am the guy that quit.” Assigned to be a guard, Cotter showed up to the training session but was alienated by Zimbardo’s agenda, as well as by his fellow guards’ gleeful plans for tormenting prisoners. “I felt more and more isolated from that group,” he recalls. So he quit before the experiment even started. “This was set up for the guards to abuse, so how could it go any other way?”

Why Zimbardo’s interpretation has persisted for so long

In his American Psychologist paper, Le Texier identifies four reasons why the Stanford Prison Experiment has remained so influential, despite conspicuous flaws. Two explanations have to do with ongoing debates around situationism—the idea that circumstances, more than personality, drive human behavior—within the field of psychology. Le Texier also concludes that:

“The SPE survived for almost 50 years because no researcher has been through its archives. This was, I must say, one of the most puzzling facts that I discovered during my investigation. The experiment had been criticized by major figures … yet no psychologist seems to have wanted to know what exactly the archives contained. Is it a lack of curiosity? Is it an excessive respect for the tenured professor of a prestigious university? Is it due to possible access restrictions imposed by Zimbardo? Is it because archival analyses are a time-consuming and work-intensive activity? Is it due to the belief that no archives had been kept?”

Finally, Le Texier acknowledges the tireless promotional efforts of the experiment’s mastermind; “in his desire to popularize his experiment,” he writes, “Zimbardo has very often made the SPE look more spectacular than it was in reality.” That’s putting it mildly. Unlocking the Truth shows clip after clip of Zimbardo flogging his findings, decades after the experiment was conducted: MSNBC, The Daily Show, a panel with the Dalai Lama, a TED Talk, etc. He shored up his legacy as the media’s favorite social psychology expert with books like 2007’s The Lucifer Effect, a best seller and APA William James Book Award winner that highlights connections between the Stanford Prison Experiment and Abu Ghraib, and by hosting the 1990 PBS series Discovering Psychology. What’s the appeal of the message he’s pushing? From police brutality to genocide, “he has a very simple explanation to these very complex world events,” Le Texier says in the series.

It shouldn’t escape our notice, either, that Zimbardo was intimately involved with several previous onscreen representations of the experiment. He co-wrote and served as an executive producer of the 1992 documentary Quiet Rage: The Stanford Prison Experiment. And the 2015 movie everyone liked so much? It’s based on The Lucifer Effect, and Zimbardo consulted on it.

What, if anything, did the Stanford Prison Experiment really prove?

Critics of Zimbardo’s work have put forth various theories as to what his experiment actually means. When you’re aware of the influence he and his aides exerted over the guards, the Stanford Prison Experiment can start to look like an exercise in confirmation bias. The BBC study, whose participants knew their conduct would be observed by a huge TV audience, might suggest that we should demand more transparency from the carceral system and similar institutions. In Unlocking the Truth, Stephen Scott-Bottoms, Professor of Contemporary Theatre and Performance at Manchester University, speaks to the effect SPE has had on the public imagination when he calls it “the most influential piece of performance art of the 20th century.”

Particularly persuasive is an argument one of the BBC researchers makes in the series. “We began to realize that actually leadership was absolutely critical,” Reicher recalls. “Because the more you look at Zimbardo’s study, you realize that the guards didn’t become guards willy-nilly. He acted as leader to tell them what to do. But without leadership, you don’t get the types of toxic behavior we saw in Zimbardo’s SPE.” In other words: The situation to which Zimbardo attributed so much power is, in truth, only as powerful as the influence exerted by its leaders.

For me, the most crucial conclusion to draw from Unlocking the Truth and other research that has challenged the SPE is that people—some of them, at least—are capable of acting as individuals regardless of the situation. Even with Zimbardo’s encouragement, not every guard turned into a monster. Cotter didn’t even stick around long enough to don his uniform. And the ones who did abuse their power often had reasons for doing so besides the reservoir of evil Zimbardo felt sure was waiting within each impressionable human soul to be tapped. Contrary to the arguments he has made over the years (Zimbardo testified for the defense in the Abu Ghraib trial), maybe people should be held accountable for their behavior within institutional or otherwise hierarchical settings. As authoritarianism trends, it’s a takeaway worth remembering.