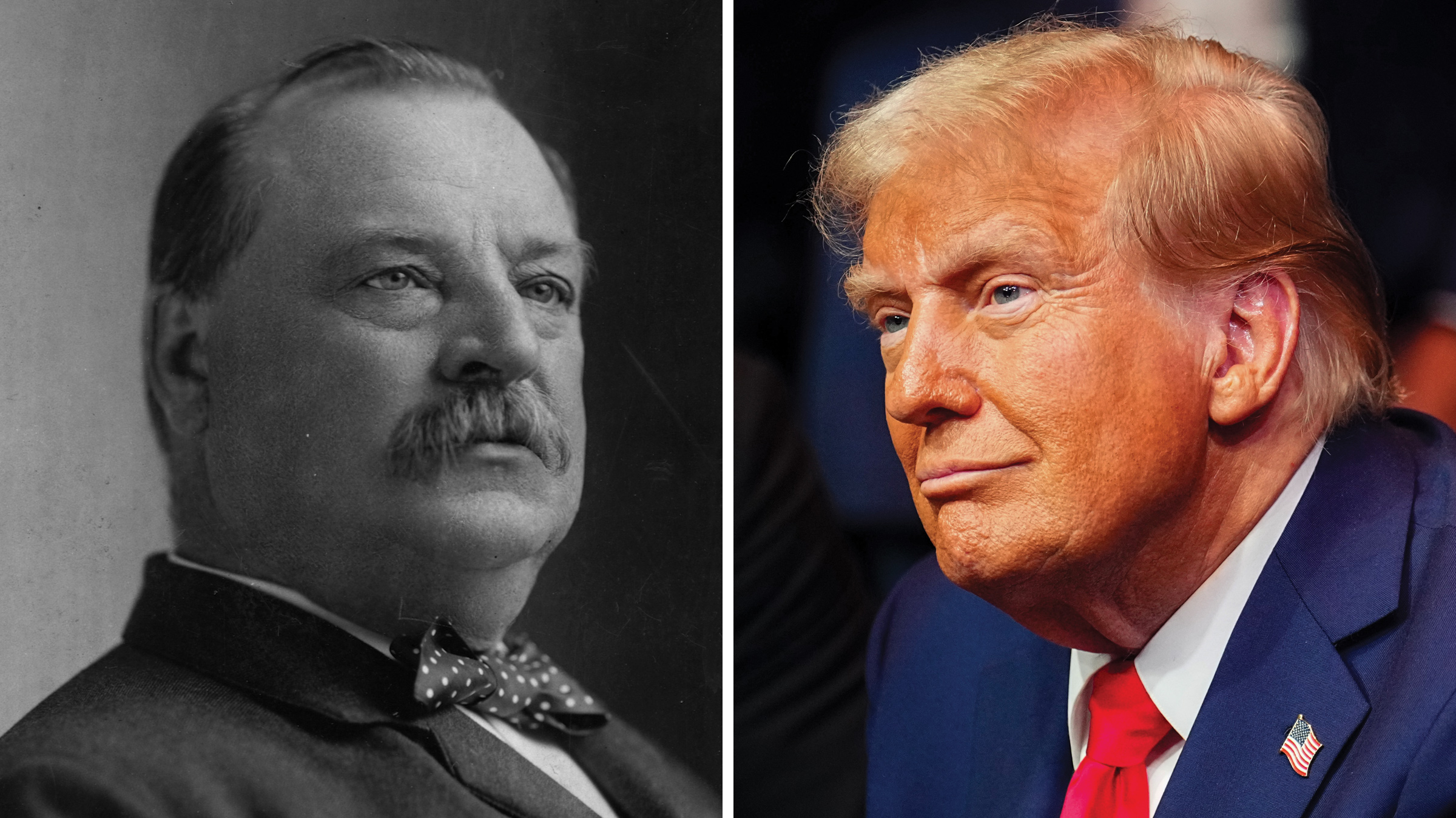

On Nov. 5, 2024, Donald Trump won a second non-consecutive term in the White House. Trump’s triumph drew comparisons to the 1892 reelection of Democrat Grover Cleveland — the only President other than Trump to regain the White House after he previously lost re-election. Cleveland won in 1884, lost in 1888, and recaptured the presidency in 1892. Like Trump, he maintained popularity within his party despite losing. This support enabled Cleveland to cruise to the 1892 nomination, and he capitalized on Republican struggles to recapture the White House. Yet, while his second election was a triumph for the Democratic Party, it ended up demolishing the party for a generation. Cleveland’s example offers a cautionary tale for Republicans in 2024: a second Trump Administration involves as many risks as possible benefits.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Grover Cleveland would have been an unlikely candidate for President in any period of American history other than the one in which he served. Born in 1837 in New York, he worked as a lawyer in Buffalo for much of the 1860s and the 1870s, a period during which the state’s Democratic Party became nationally renowned for corruption because of the rule of the Tammany Hall machine.

Cleveland entered politics by winning election as sheriff of Erie County in 1870. His political career quickly soared because he avoided the taint of corruption that plagued many New York Democrats. By the beginning of the 1880s, he had cultivated an appreciative group of supporters who helped propel him to the governorship in 1882 on a platform of reforming the state’s civil service and combating corruption.

Cleveland’s governorship got off to such a successful start that only two years later, Democrats made the New Yorker their presidential nominee. Once again, he ran as a reformer against the scandal-ridden Republican candidate James Blaine, and he became the first Democrat to win the presidency since 1856.

Read More: Donald Trump, Grover Cleveland, and the History of Winning Back the White House

President Cleveland’s first term was remarkably uneventful, and few major pieces of legislation passed Congress. He dithered over whether he would support a high or a low tariff on imported goods, which was the major economic issue of the day. Only in 1887 did Cleveland come out in support of a low tariff on imported goods. This policy outraged American manufacturers, as they believed that the proposed bill did not provide them with enough protection from foreign competition. The opposition of influential manufacturers and high-tariff supporters in both major parties doomed the bill in Congress. The bill’s defeat deprived Cleveland of an achievement to tout during his reelection campaign in 1888.

Cleveland’s penchant for harsh rhetoric also alienated many constituencies. He owed his first election to Republican defectors often referred to as “Mugwumps.” However, Cleveland angered these supporters because he proved willing to replace Republicans with Democrats in positions throughout the federal civil service.

Yet, this wasn’t enough for many members of his own party, who complained that Cleveland did not appoint enough Democrats. The President didn’t take their concerns seriously, often dismissing them with mockery and sarcasm. He responded to one patronage request by stating “Ah, I suppose that you mean that I should appoint two horse thieves a day instead of one!” This posture soured his relationship with many Democrats.

Cleveland also had a fraught relationship with the military. He became infamous by repeatedly vetoing pension requests by Union veterans as they suffered from numerous physical and psychological ailments tied to their service. He mocked the morphine addiction of one applicant, and he dismissed the idea that “sore eyes” were a side effect of the chronic diarrhea of another pension applicant. Cleveland also tried to return Confederate flags held in the North to white Southerners in an attempt to further the post-Civil War reconciliation between the North and South. Additionally, he appointed numerous Confederate veterans to his cabinet, and even one to the Supreme Court during his first term. These actions alienated many Union veterans.

Cleveland’s divisiveness cost him reelection in 1888. While he won the popular vote, he fell to Republican Benjamin Harrison in the Electoral College. His popular vote victory enabled Cleveland to remain a front-runner for the 1892 Democratic nomination.

And by 1890, his fortunes were looking up. Harrison’s presidency had run aground after he and congressional Republicans passed a high tariff that led to defections from their ranks. Republican legislators also failed to pass a major civil rights act that could have provided federal marshals to guard polling places and protect African-American voters. This failure rendered Black voters unable to vote in a many places, depriving the GOP of support from the party’s most loyal constituency.

These mistakes helped put Cleveland back into the White House. Yet, the glow of 1892 was temporary for the new President and for his party. The Panic of 1893 began shortly after his reelection, and it would prove to be the worst economic crisis to plague the nation until the Great Depression. The panic led to widespread unemployment and even to starvation.

Cleveland refused to provide federal aid to those in need during the crisis, despite marches designed to draw attention to the plight of unemployed workers. He also refrained from making adjustments to his economic platform to try to fix the struggling economy. Instead, he clung to support for a low tariff, and crucially, to a strong gold standard.

This latter decision fatally fractured Cleveland’s party. Western Democrats in particular longed to have the price of silver be valued at 16-to-1 against gold rather than the standard 32-to-1 ratio — which would have improved their local economies dramatically. The President, however, refused to compromise.

The low tariff that Democratic congressmen passed in 1894 did nothing to stop the damage caused by the Panic of 1893. The result was a wipeout of the Democratic Party in the 1894 midterms. The losses destroyed the party outside of the South for a generation. Democrats would not regain the House of Representatives until 1910 or the Senate until 1912.

The miserliness of Cleveland’s first term had helped him to win a second term, but in his second term it destroyed his popularity. Even after his party’s midterm wipeout, the president ignored continued pleas for either a high tariff or a high valuation of silver in relation to gold, which increasingly alienated him from his own party.

By 1896, the relationship was so bad that Cleveland refused to back the Democratic nominee for president, William Jennings Bryan, because of his stance on silver. At his behest, even Confederate veterans in Cleveland’s cabinet — who had supported Democratic candidates since the 1860s — backed the third-party candidate John Palmer over Bryan. Cleveland simply didn’t see intraparty harmony as a major goal for presidents.

Even after he left the White House, Cleveland continued to actively oppose Bryan’s pro-silver views within the Democratic Party, which made him a pariah until his death in 1908.

Trump shares many similarities with Cleveland — and the parallels between the two men are not encouraging for Republicans. Both showed little interest in party unity or the broader success of their parties. They also both detested the media throughout their careers, dismissed the beliefs of the majority of economists on tariffs, and railed against “establishment” politicians within and outside of their parties.

In the weeks since Election Day, Trump has given little indication that he has changed since his first term. This raises the specter of Cleveland: he, too, remained the same man as he returned to the White House. And as he demonstrated, comebacks can be temporary for someone who doesn’t learn from the mistakes of his first term. Such a President can quickly remind voters of why they rejected him in the first place, with his party paying the price. No one knows how Trump’s story ends, but the history of Cleveland suggests that it might not be good for Republicans.

Luke Voyles is a Ph.D. student at the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa. He studies Confederate veterans and their role in U.S. politics.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.