Earth may be home to the most glorious beaches in the solar system today, but 3 billion years ago, Mars might have claimed the crown. That’s the conclusion of a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, based on the work of a Chinese and American team of researchers working from data gathered by China’s Zhurong Mars rover. Where there’s a beach, the researchers suggest, there might well have been life.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

It’s long been all but settled science that Mars was once home to copious amounts of water. Its surface is stamped with ocean and sea basins and etched with ancient riverbeds, deltas, and alluvial fans. The water didn’t last long—just the first 1.5 billion years of the planet’s 4.5 billion year lifetime. Relatively early in its history, Mars lost its magnetic field, which allowed the solar wind to claw away most of its atmosphere; with that, much of the water sublimed into space. It’s in the sites of the vanished water that NASA and the Chinese National Space Administration have landed their rovers, studying not just the ancient geology, but the possibility of signs of ancient biology. One such formation, Utopia Planitia, a large plain in Mars’s northern hemisphere, was selected as the landing site for Zhurong, which touched down on Mars on May 15, 2021. The northern lowlands are believed to have been home to oceans that covered up to one third of the Martian surface.

Read More: What Makes Pluto So Intriguing

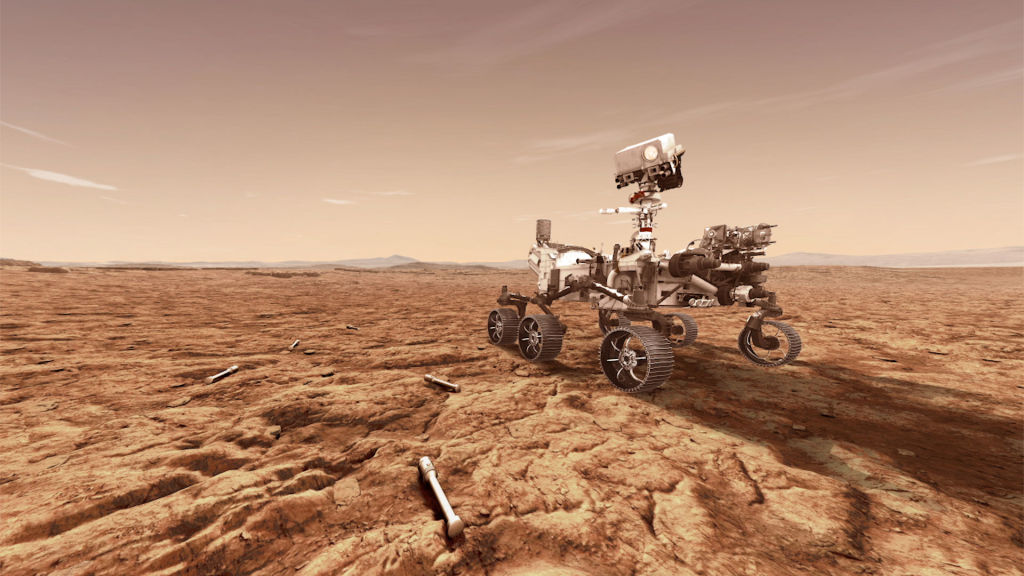

Zhurong has conducted some of its sleuthing into Utopia Planitia’s watery past with high-resolution cameras, which captured images of rocks that have the layered, pebbly look of sedimentary objects. But it is the rover’s ground-penetrating radar that has returned the most newsmaking finds. The instrument is capable of penetrating up to 330 feet below the surface, but Zhurong did not have to go nearly that deep to hit paydirt. Along a 0.8-mile stretch in Utopia Planitia, it discovered 76 geological reflectors—or discrete regions of rock that bounce seismic or radar waves back to the surface. Reflectors are hardly uncommon below ground; they’re what the shallow innards of worlds are basically made of. But these reflectors were special.

For one thing, they were all sloping in the same direction, at an angle of six to 20 degrees. They also extended to depths ranging from 30 to 115 feet. That made them strikingly similar to the depth and inclination of underground beachfront formations on Earth. The researchers cited the Bay of Bengal as a close Earthly analog to the Martian reflectors, but they also matched them up against 21 other beaches on Earth, which incline at angles of four to 26 degrees.

Read More: NASA’s New, $4 Billion Space Telescope Will Unravel a Great Cosmic Mystery

“We’re finding places on Mars that used to look like ancient beaches and ancient river deltas,” said Benjamin Cardenas, assistant professor of geology at Penn State University and a co-author of the paper, in a statement that accompanied its release. “We found evidence for wind, waves, no shortage of sand—a proper, vacation-style beach.”

It wasn’t a given that the angled reflectors were indeed formed by a vanished ocean. They could have been sculpted by wind, but the investigators ruled that out because there would have been more chaotic variation in the angles along the 0.8-mile stretch, rather than the gradual sloping that Zhurong documented. Rivers could have been responsible too, but the area Zhurong studied lacked the telltale river valleys that would have been left behind after the water evaporated.

Read More: NASA’s Mars Rover Mission to Bring Samples Back Home From the Red Planet Is at Risk

“Therefore,” the authors wrote, “we conclude that the dip reflectors under the Zhurong landing site are most consistent with those formed in a coastal environment.”

Could that coastal environment have given rise to life? The authors do not rule it out. “This stood out to us immediately because it suggests there were waves, which means there was a dynamic interface of air and water,” Cardenas said. “When we look back at where the earliest life on Earth developed, it was in the interaction between oceans and land, so this is painting a picture of ancient habitable environments, capable of harboring conditions friendly toward microbial life.”