The 1988 Las Vegas Consumer Electronics Show (CES) was the main showcase for new electronics and video games. It featured everything from new computer systems to cutting-edge technologies and car stereos. It even had a separate section for the porn industry. Every major U.S. publisher of computer games had a booth displaying the games they hoped would sell that year. As a professional show, it attracted corporate buyers, members of the press, and people like me who were looking for the next great video game.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

I flew there from Japan, where I was running my publishing company Bullet-Proof Software, hoping to find something new to release. Unbeknownst to me, that weekend I would find a diamond in the rough—and make gaming history.

As I walked into the computer games section of CES, I found myself standing in one of several huge halls with high ceilings. I began to explore the aisles, finding the space a bit daunting in its vastness, with its bright lights and cacophony of sounds ranging from blaring rock music to symphonic mood music and a competing clamor of video game sound effects. The aisles were lined with station after station of new computer games on display. Each station had a line of people waiting for their turn at the controls of some new game to get a taste of the style, the look, and the all-important gameplay.

I saw Super Mario 3, Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest III, Arkanoid, King’s Quest IV, the Legend of Zelda, and the Fool’s Errand, and I tried a few of them out. I was amazed by the impressive audiovisual experiences on display. The industry had taken a big leap forward.

Read More: The 50 Best Video Games of All Time

As I wandered among the booths, I found my way to the Spectrum Holobyte booth. There, on one of their dozens of monitors, was a very crude-looking, simple, real-time puzzle game called Tetris.

I hopped in line and waited.

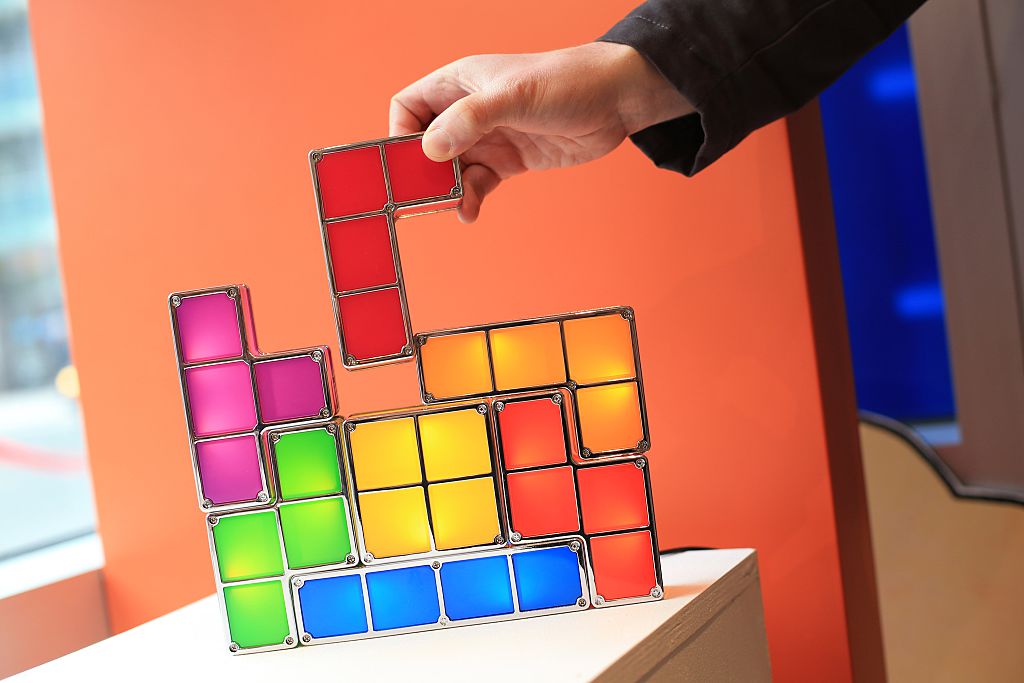

Finally my turn came. I found myself playing one of the simplest games I’d ever seen. It consisted of colored blocks of different shapes falling from the top of the screen. That’s all. At first, I didn’t take it seriously, but I played on. Maybe there was more to this game than met the eye.

The competing games around me all had better animation, big explosions, deep stories, better musical scores. Tetris lost to all the others in every respect—except for game play. I was standing there moving little colored squares around the screen. It looked like one of those slow geometry puzzles, only this was in real time. It was a pure game. No frills of any kind, just game play.

When my turn was done, I stood there watching other people explore it and did a mental review. No animated characters. No story. No fancy graphics, only simple manipulation of clumps of falling blocks to fill gaps in the leftover spaces at the bottom of a well. Seriously? How could this be a computer game in 1988?

Computer games are generally built to fit a certain audience. More often than not, this audience is young men. This means that they tend to be rite-of-passage games where young men can prove their prowess somehow.

Tetris was nothing like the other games surrounding it at CES. It was way too simple to be a normal computer game. And yet, it pulled me right in.

Read More: An Interview With the Creator of Tetris

What was it that made me come back? Why was this game so compelling? Was it because it was about creating order out of chaos? Was it so satisfying to build and clear lines? Why did this game leave such an impression on me? I think it was because of its simplicity. Whoever came up with this game was a mathematical genius.

Other publishers were undoubtedly overlooking Tetris because it appeared to be a throwback to a time when computers didn’t have graphics cards—and as I would find out later, that was its creator’s intent. This was pure geometry, no extra nonsense.

This could well be a perfect game.

My mind was racing. Did I only like this game because I like puzzles? I didn’t know many other people who were into mathematical puzzles. Would Japanese people feel the same way I did? I would have to go back and find out.

I stood in the Tetris line four times, playing again and again until I put the high score on the machine, replacing the name at the top of the leaderboard. This game was working its magic on me. I was already addicted.

At the end of each game, this text scrolled across the screen:

TETRIS WAS INVENTED BY A 30-YEAR-OLD SOVIET RESEARCHER NAMED ALEXI PAZHITNOV WHO CURRENTLY WORKS AT THE COMPUTER CENTER [ACADEMY SOFT] OF THE USSR ACADEMY OF SCIENTISTS IN MOSCOW . . .

I looked at the copyright notice on the box:

©Mirrorsoft and Andromeda Software Licensed to Sphere

I realized that I already knew the major players, some better than others. The very fact that these fascinating people—as well as a Russian developer!—all had a stake in Tetris intrigued me all the more. In some ways, the game became less important to me at that point than the story behind it and the people involved.

Something told me to delve deeper into this Tetris game.

This is where the real adventure began.

Excerpted from The Perfect Game: Tetris: From Russia With Love by Henk Rogers, published by Di Angelo Publications.