Amid the measles outbreak that started in Texas and is now believed to have spread to four other states, many people might be wondering: do I need to get a measles vaccine booster?

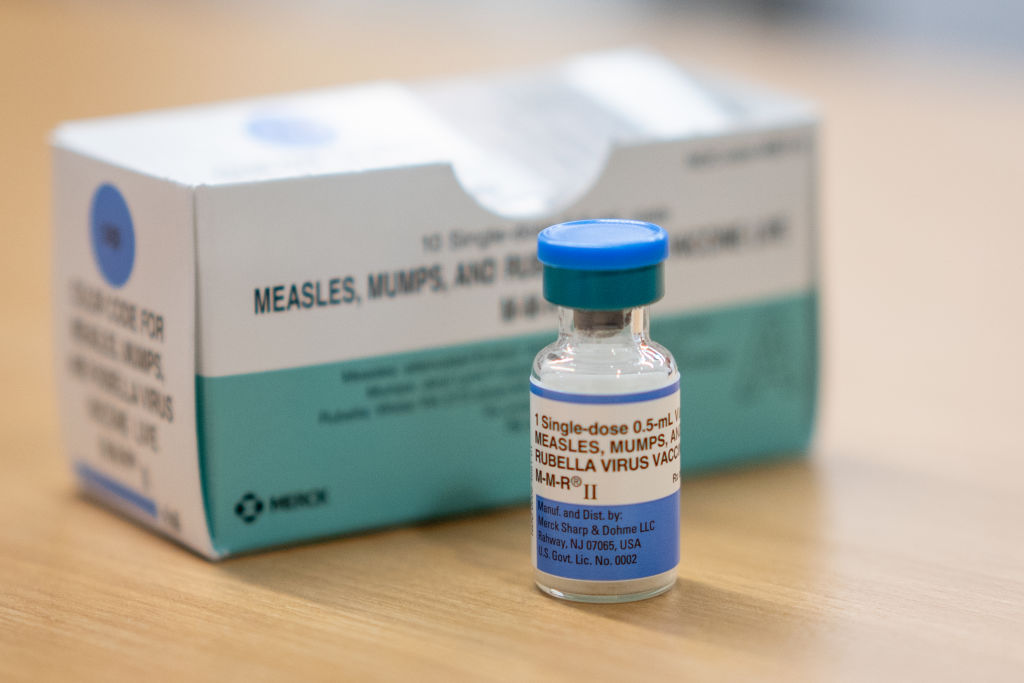

Measles is a highly contagious airborne disease that can lead to severe complications, including death. It’s also vaccine preventable through the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, which is typically administered in childhood in two doses. More than two decades ago, measles was declared eliminated from the U.S., thanks in large part to a successful vaccination program. But in recent years, vaccination rates have declined and measles cases have soared. In 2024, there were 285 reported measles cases in the country, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Four months into 2025, the agency has received reports of 800 confirmed measles cases. Of those, 96% were in people who were either unvaccinated or had unknown vaccination status.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

So far in 2025, two children in Texas have died of measles-related complications; both of them were unvaccinated. A third person, an unvaccinated adult in New Mexico, tested positive for measles after death, though the official cause of death is still under investigation, according to the CDC. Before this year, the last confirmed measles death in the U.S. was in 2015, according to the CDC.

Read More: Why Measles Cases Are Rising Right Now

Public health experts say that the best way to protect yourself against measles is to get vaccinated. The MMR vaccine is safe and effective; according to the CDC, two doses are 97% effective against measles. People who don’t get the MMR vaccine in childhood can still get it later in life, says Dr. Ravi Jhaveri, a professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and the division head of pediatric infectious diseases at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

The CDC has said that most people who get the MMR vaccine will be protected for life, and there are no official recommendations to get a third dose of the vaccine during a measles outbreak.

“The vast majority of people with two doses are protected [and] do not come down with measles,” Jhaveri says. “We have decades upon decades of experience that two doses has been safe and effective, and when we maintained two doses at a very high level across our population, we were seeing very few, if any, outbreaks.”

Still, that doesn’t mean a booster is never needed for other types of diseases. According to Jhaveri, there are two important factors that help make that determination: the genetic variability of the virus and the nature of your immunity. The viruses causing the flu and COVID-19, for instance, have a lot of genetic variability, which is why public health experts recommend getting a new vaccine against those viruses every year. People also get booster shots for tetanus because antibody levels against the bacteria wane over time and if someone has a high-risk exposure—such as stepping on a rusty nail—doctors err on the side of vaccinating them afterward, Jhaveri says. But measles, he says, is more genetically stable and both doses of the MMR vaccine “allow for you to have antibody levels that are high enough to protect you and also allow your cells to respond in case you are exposed, to prevent you from getting infected.”

Jhaveri says that, as people get older, their immune system typically doesn’t work as well, so “theoretically, there may be some drop in measles immunity.” Only about three out of 100 people who are fully vaccinated against measles will get the disease if they are exposed to the virus, according to the CDC. But a vaccinated person who does get the measles typically has much milder symptoms and is less likely to spread the disease to others, compared to someone who is unvaccinated. According to the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, about 90% of unvaccinated people who are exposed to the virus will get measles.

There is a group of people who may need to consider getting vaccinated again: according to the CDC, people vaccinated before 1968 with an older version of the vaccine, an inactivated one, should be revaccinated with at least one dose of the vaccine we use now, a live attenuated measles vaccine. That’s because the inactivated vaccine, which was available from 1963 to 1967, was not as effective as the version we use now.

Jhaveri points out that the ongoing outbreak is mostly among unvaccinated people, not those who have been vaccinated, and so getting a third dose would be unnecessary.

“The reason we’re seeing outbreaks now is because we have big pockets across our population that aren’t getting those two doses,” Jhaveri says. “So convincing the people who are doing the right thing to do it more is not where the effort really needs to go; it’s to convince those people who don’t see the benefit of the two doses … that they should get vaccinated.”