The number of measles cases in the U.S. has reached a 33-year record high, years after it was officially eliminated in the country, prompting public health experts to sound the alarm that other diseases could experience a similar resurgence.

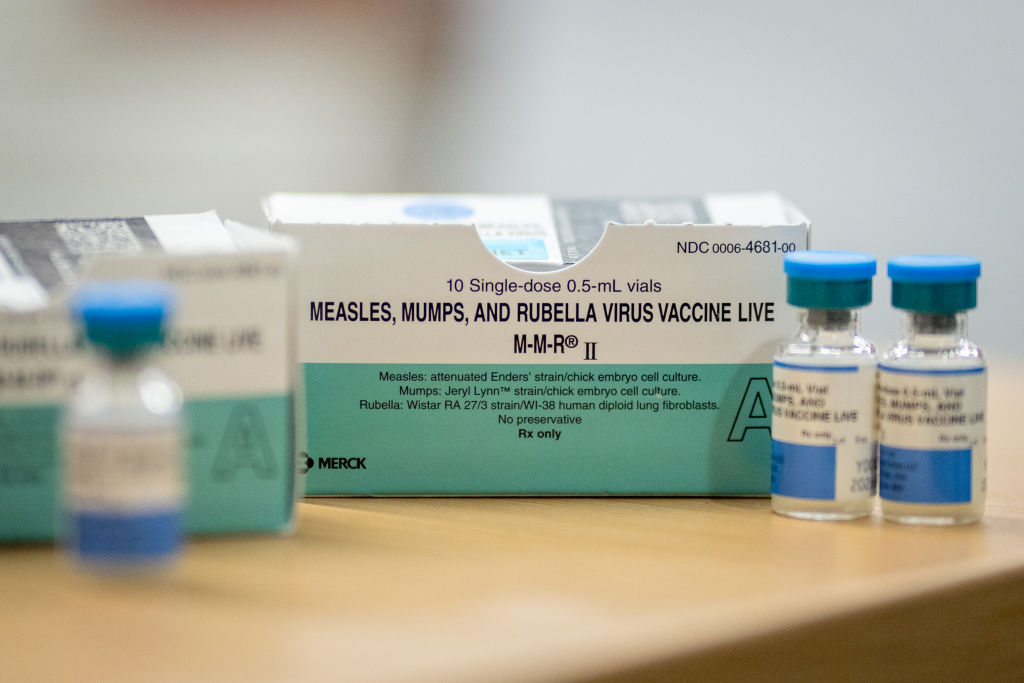

There have been 1,288 confirmed measles cases in the U.S. this year as of Tuesday, according to the latest data released by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). That’s the largest number of cases reported in the country since 1992—eight years before the disease was declared eliminated from the U.S. Measles is a highly contagious disease that can lead to serious health complications, including death, but is vaccine preventable through the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. Public health experts have largely credited its official elimination from the U.S. to a successful vaccination program. Over the past few years, however, vaccination rates have decreased, and the number of measles cases has soared. In 92% of the cases confirmed in the country so far this year, CDC data show, the person who got measles was unvaccinated or their vaccination status was unknown.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Read More: Do You Need a Measles Vaccine Booster?

The alarming new case milestone didn’t come as a surprise to many public health experts.

“I was expecting us to hit this record this year,” says Katelyn Jetelina, an epidemiologist and founder of the newsletter Your Local Epidemiologist. “But it was more of the reality hitting that this has finally happened—that we are really here in this moment in 2025. And I’m very concerned about what it means for the future.”

Experts warn that the rise in measles cases could be a harbinger for an increase in the prevalence of other diseases too.

“Measles is the most contagious virus on Earth, so it’s often the first to resurge when vaccination coverage declines,” Jetelina says. “We’ve managed to keep measles at bay for decades thanks to high vaccination rates, but those rates are slipping.”

Experts have pointed to a variety of reasons for falling vaccination rates, including an increase in vaccine hesitancy amid the COVID-19 pandemic and as vaccine skeptics like Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. have gained prominence.

Kennedy, who has long spread disinformation about vaccines, last month removed all 17 members from a CDC vaccine advisory committee and appointed in their place several members who have previously expressed vaccine skeptic views. The new committee met for the first time weeks later, voting to stop recommending flu shots that contain thimerosal, an additive that the anti-vaccine movement has attacked for years despite numerous scientific studies finding no evidence that the trace amounts contained in some vaccines are harmful. The committee also indicated that it will review some childhood immunizations, leaving the door open for possible changes in the schedule of childhood vaccinations.

The threshold for herd immunity against measles is generally considered to be 95%, meaning that 95% of people need to be vaccinated against the disease to prevent it from spreading. Data indicate that the U.S. has now dipped below that threshold: In the 2023-2024 school year, vaccination coverage among kindergartners was just 92.7%, according to the CDC.

If this trend continues for other immunizations, experts say, it’s possible other diseases could resurge. Which diseases those could be, though, “depends on how bad this is going to get,” Jetelina says. Many diseases have a lower herd immunity threshold than measles—polio’s, for instance, is around 80%—so “it’s going to take a lot more” for vaccination rates to drop that drastically, she adds.

Michael Osterholm, the director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) at the University of Minnesota, says he fears that the U.S. could face increasing cases of mumps and rubella, since the MMR vaccine protects against those diseases, too. The U.S. has already experienced a rise in whooping cough cases, due in part to declining vaccination rates, as well as the introduction of a new type of vaccine for the disease in the 1990s to replace one that was more effective but also had more side effects.

“I think right now, all vaccine preventable diseases are, in one way or another, at risk of experiencing major increases in illness,” Osterholm says. “I think you’re going to begin to see over time more of these vaccine preventable diseases coming back, and we’re going to start seeing kids seriously ill and dying.”

Public health experts describe feeling like America has suffered from a kind of amnesia over how serious many of these diseases are and why officials have encouraged getting vaccinated against them. Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, says he wishes that more people understood how dangerous measles can be.

“Those two little girls—that six-year-old and eight-year-old that died in west Texas—were perfectly healthy children,” Offit says. “The reason they died is because measles can kill anybody, and I think we live in this sort of state of blissful ignorance, and you never think it’s going to happen to you until it happens to you.”

Thirteen percent of the confirmed measles cases in the U.S. this year have resulted in hospitalization, according to the CDC, including 21% of cases in children five or younger. Three people are confirmed to have died.

At the same time, experts stress that this issue goes beyond measles.

“I want people to realize that this is not just about measles,” Jetelina says. “It’s far more than an infectious disease flare-up; it’s a symbol of broken trust, eroded progress, rise of individualism replacing collective good, this system that’s cracking under the weight of disinvestment and distrust.”

“Measles is a canary in the coal mine, and it signals something that has gone seriously wrong,” she continues. “It’s an unraveling of decades of progress, and there’s a lot that needs to be done so we don’t keep going backwards.”