In 2020, OpenAI introduced GPT-3, a large language model used to produce a variety of computer codes and other language tasks. Two years later, the company produced its Artificial Intelligence (AI) chatbot, ChatGPT. By 2023, ChatGPT had over 100 million users, making it the fastest growing consumer application to date. Contributing to swift growth, AI companies have targeted corporations for investment and framed their tools as necessary for businesses to remain competitive. Their message is clear: companies, and workers, that fail to use AI will be “left behind.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Today’s tech companies are encouraging other companies to require employees to use their products. This business-to-business messaging is a sharp departure from the last major revolutionary technological change—personal computers (PCs) and the internet.

In the 1990s, tech moguls, interested in individual consumers rather than corporate buyers, used utopian language to describe the internet as a marker of human progress that could improve productivity, provide easier access to consumer goods, and increase leisure time. Why? They wanted to sway the public to purchase the internet for home use.

Today, tech companies often downplay the criticisms of workers who are now being pressed to use technology that could transform, reduce, or eliminate their own jobs. Some employers may see replacing workers with AI as a positive, but the end users (workers who could lose their livelihoods to this technology) might likely take issue with the projected trend.

To be sure, 75% of OpenAI’s revenue currently comes from consumer subscriptions. And the AI-powered Studio Ghibli meme trend illustrated AI’s viral popularity among individual social media users. But the general consumer cannot provide the necessary profit to keep up with the billions of dollars shareholders are investing. Open AI has told investors it won’t generate profit until 2029 and until then, it expects to lose $44 billion. The company, therefore, has shifted much of its focus from individual to business consumers with products such as ChatGPT Enterprise, ChatGPT Team, and ChatGPT Edu. Thus, the burgeoning AI industry is being marketed significantly differently to how the internet was first marketed.

A look back at the 1990s shows how tech companies rely on predictions about the future to make decisions about how they sell a new product. In both cases tech firms are making predictions about who will hold power in the future and are making specific choices about how to encourage consumers to embrace this future.

The internet has roots in Cold War-era government projects, but by 1995, the shift to “dot coms” and development of web browsers such as Microsoft Explorer made the internet accessible on PCs. America Online (AOL) offered internet services and new personal email addresses for consumers to enjoy electronic communication for the first time. In 1995 and 1996, Yahoo and Google respectively, debuted user-friendly search engines to make navigating the internet easier. And in 1999, router transmission sped everything up, making it more practical for use inside the home. By the new millennium, some 50 million Americans had access to electronic communication, commerce, and information.

Read More: ChatGPT May Be Eroding Critical Thinking Skills, According to a New MIT Study

This meteoric rise of personal internet use required a marketing strategy that assured customers about the safety of bringing the World Wide Web into their homes.

At first, the internet had a negative image as a wild new frontier. Mainstream media fixated on cyberporn and fraud. Film industries captured this “internet frenzy” by portraying the Web as a lawless space where vigilante “cyber-cowboys” fought nefarious hackers. Meanwhile, films such as The Net (1995) and Hackers (1995) portrayed a world in which an over-reliance on computer technology made individuals susceptible to identity theft. To broaden the internet’s consumer base, online spaces needed a new image.

American media companies helped provide it. In 1995, for example, NBC announced plans to partner with Microsoft in its launch of MSNBC Cable. Combining excitement for the internet with enthusiasm for cable TV, MSNBC distinguished itself from other 24/7 news channels with its “interactive” website. There, viewers could access more information and respond to news stories in real time.

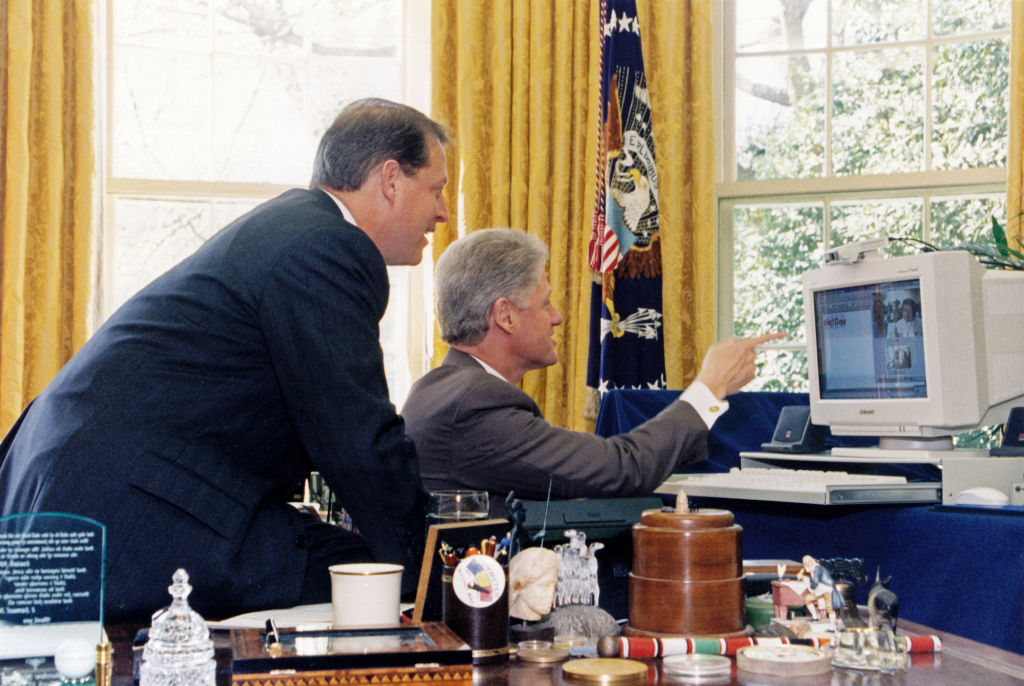

The federal government also played a role in rebranding the Web. During the Cold War, the U.S. invested in internet technology for the military and helped develop a pioneering communications system primarily used by academics. But by the 1990s, as demand grew for internet access and more commercial providers offered online services to the broader public, political leaders saw opportunities to generate economic growth. President Bill Clinton advocated for privatization of the internet to promote competition and create jobs. By growing the tech industry, Clinton claimed, the powerful tool could be used to improve education and expand access to healthcare.

Tech companies capitalized on this political momentum and partnered with the popular press. In his book, The Road Ahead (1995), Bill Gates, cofounder of Microsoft, predicted that this new technology would “enhance leisure time and enrich culture by expanding the distribution of information.”

In newspapers, discussions about the accessibility of PCs and the internet also emphasized such benefits. In a 1996 op-ed, Gates argued that failure to invest in such tech presented the potential for poor, rural, minority, and aging communities to be “left behind.” Without broad access to the internet, he claimed, the “information gap” would widen and lead to generational tensions and class inequality, where “one portion of our society perceives the world quite differently than the other.”

To bridge this divide, Gates proposed tech companies work with governments and non-profit organizations to bring PCs and free internet service to libraries, schools, and community centers. Accessibility was key; Gates explained that the PC industry was taking a “Henry Ford-type of approach” by making a less expensive yet powerful product “if an ever-broader market is to embrace it.” Like Ford who increased sales by making automobiles broadly affordable, Gates emphasized the benefits PCs offered lower-class Americans to justify the growth of computer companies like Microsoft.

Read More: What to Know About the Real Y2K Problem Before You Watch <i>Y2K</i>

In 1997, roughly 40% of American homes had a PC, compared to 98% of all homes with televisions. To make PCs and the internet a household staple, companies converged computers with television sets through “Web TV”: a television set with internet access. A start-up company developed Web TV in 1995 and licensed the product with Sony and Philips to sell its television attachment that associated PCs with entertainment and the home. Pitched as a family-friendly technology, newspapers described how users could browse recipes while watching cooking shows or to learn about regional salmon while watching a fishing program.

Indeed, computer and TV manufactures drew upon romantic ideas of television and the family to advertise Web TV. Over the previous decade, teenagers had been lured away from shared domestic spaces by personal TVs, video games, and PCs. One Wall Street Journal article asked readers to picture “a family turning on a big-screen TV to browse the World Wide Web.” In the same article, a representative from Harman Interactive claimed “Web TV” would restore the hearth and bring “the family together again.” Vice President of design at Thomson Consumer Electronics called it a “home-entertainment product that we think the entire family will share.”

The hype around “Web TV” unifying the family, however, was mostly that. Eventually, as tech companies introduced new, more portable personal computing devices, including tablets and smart phones, and new forms of entertainment media, such as streaming services and social media, technology spurred what some commentators deemed the “privatization of American leisure.” Other early promises about the potential of digital technologies have gone unfulfilled; recent studies also suggest that the increase in digital technologies have not had a noticeable impact on achievement in schools.

Whether the proliferation of AI technologies improves American life remains to be seen. Since the development of AI chatbots in 2022, tech moguls like Gates have touted generative AI as the most revolutionary technology since computers, the internet, and mobile phones—and such a game changer that, as Gates has predicted, it will replace many teachers and doctors over the next decade. Like in the 1990s, these types of predictions should not be taken at face value.

It is not a foregone conclusion that AI will render certain jobs obsolete nor humans inconsequential to society. While such dystopian rhetoric has generated fear and concern among workers, companies are being sold a vision of the future that promises reduced wage costs and increased profits. The past shows us that advancements in technology do generate economic and social changes, however those changes are not always in line with the promises made by the producers of technology.

Kate L. Flach is an Assistant Professor at California State University, Long Beach where she teaches and studies the history of media and technology.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.