Students at the Tahoe Truckee Unified School District in California dine on locally sourced fruits and vegetables, homemade pozole (a Mexican stew), and fresh tuna poke bowls. Food in the school district is free of high fructose corn syrup, artificial dyes, and additives. Most of it is cooked from scratch by a full-time kitchen staff, and, like about 29% of other districts in the country, everyone eats for free.

The district’s meals, in other words, are about as good as it gets in the U.S.—and a prime example of how to improve public-school lunch programs. They’re also exactly the type of healthy, nourishing food that U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and his Make America Healthy Again movement say they want to be served across the country. In May, Kennedy promised “dramatic” changes to school lunch programs, which he called “poison” because he said they contained high levels of ultra-processed foods.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

But this success won’t be easy to replicate. Tahoe Truckee has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars annually since switching to so-called “scratch cooking” more than a decade ago—making food in district kitchens rather than just buying premade food and heating it up. Last year it spent about $400,000 on its school meals program with help from the district’s general fund, an unrealistic amount for most other districts.

“Our food service program is generally not in the black,” says Todd Rivera, the district’s assistant superintendent and chief business officer. “Before scratch cooking, the cost was pretty nominal, but as we added up staff and built up the program, we started to see the cost increase.”

Read More: Why So Many Women Are Quitting the Workforce

School meals have been changing since at least 2010—mostly for the better—when the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act passed in the Obama Administration aiming to improve the nutritional quality of school meals and increase access to healthy food for kids. When the nutrition standards from the law went into effect in 2012, they limited calories, reduced sodium and saturated fats, and increased the amount of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains required in school meals.

Many of those standards were weakened during the first Trump Administration—even as Agriculture Secretary Sonny Purdue vowed to “make school lunches great again.” While many schools have added more vegetables and whole grains since 2012, nutritionists and advocates have their sights set on a much higher bar. They want more districts to transition to scratch cooking, as the Tahoe Truckee district did, and make school breakfasts and lunches in their own kitchens with their own staff.

The challenges of making food from scratch

The transition to scratch cooking is difficult, expensive, and likely impossible for some districts without making radical changes. Some schools, especially those with older buildings, don’t even have kitchens, so cooking meals from scratch is not doable. Cooking from scratch also requires trained staff who know how to work in a large-scale kitchen.

Making the upgrades to build a suitable kitchen—or even having enough electricity or power to add appliances—is an extremely costly proposition.

“I’ve been to districts where I’ve asked, ‘Why don’t you get a walk-in freezer?’ and they say, ‘I don’t even have the electrical infrastructure to support a walk-in freezer,’” says Donna Martin, a registered dietitian nutritionist who has worked in school nutrition for over 30 years, most recently at Burke County Public Schools in rural Georgia.

Tahoe Truckee switched to scratch cooking in 2006, when the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) required districts who participated in the National School Lunch Program to create a wellness policy that included incorporating community input. At the time, heat-and-serve was the industry standard, says Kat Soltanmorad, the district’s current director of food and nutrition services.

A group of concerned parents started pushing the district to serve fewer processed foods, and by the time Soltanmorad joined in 2012, she had a mandate to try to transition to scratch cooking. She started scratch cooking test recipes three days a week with input from parents. One parent, for instance, suggested a recipe for a chocolate beet muffin that the school still serves today.

Read More: What We’ve Learned from the Texas Measles Outbreak

One of the most difficult steps, Soltanmorad says, was to build up staff and find people with culinary experience. Because the school district wasn’t hiring full-time workers at the time, it had a hard time competing with restaurants, which typically offer higher pay. “We’re competing with all the other jobs that aren’t three hours a day,” she says. The district slowly transitioned to full-time jobs that come with benefits and wages that are competitive with the private sector.

More schools are transitioning to scratch cooking now, but the staffing costs and facility requirements are difficult for some to overcome. Costs of equipment like food warmers and refrigerators have gone up dramatically since the pandemic; Soltanmorad says she was recently quoted $11,000 for a piece of equipment that cost just $2,500 in 2019.

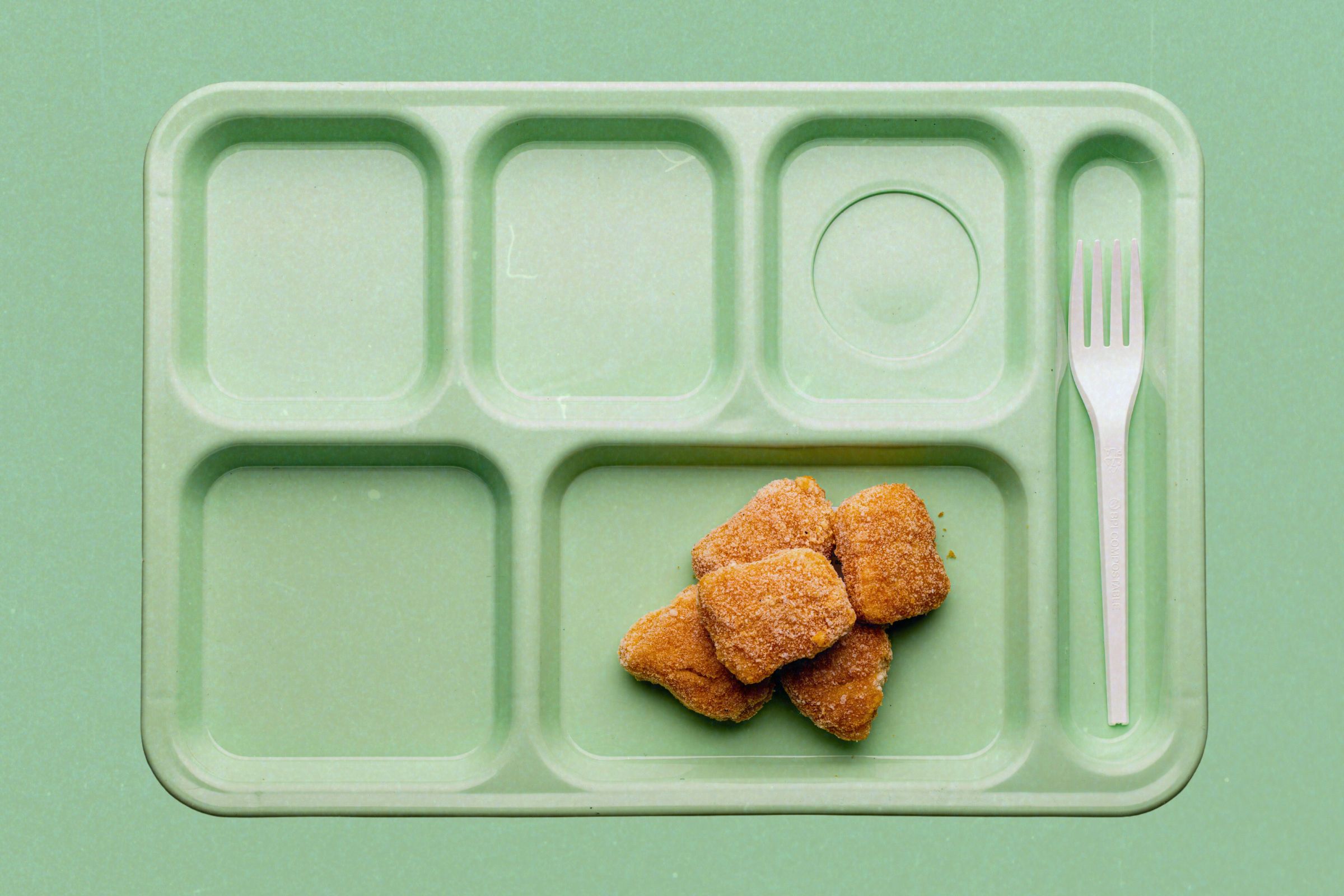

Rather than deal with all these hassles, it’s much easier for schools to just get pre-made food like chicken nuggets and warm them up. “Making that change to scratch cooking is extremely challenging for districts, because you’re going up against an industry that’s not set up for that,” Soltanmorad says.

How schools get the food they cook

Another reason schools struggle to make healthy lunches is how they acquire some of the food they cook. Districts get a certain amount of money allocated to them from the USDA. They then can buy either whole foods like ground beef and canned vegetables from the USDA with those dollars and cook those in their kitchens, or divert those whole foods from the USDA to industry, which processes them into meals. Even Tahoe Truckee still diverts some of its chicken to a processor to make mandarin orange chicken.

The USDA procurement rules sometimes make it difficult for schools to access fresh, locally sourced foods, says Katie Wilson, executive director of the Urban School Food Alliance, which represents 19 of the largest school districts in the country. “It’s the procurement rules that are constraining us,” she says.

Her organization is working to change the procurement process so schools can get access to more local food. It recently ran a pilot program that pressured providers to offer antibiotic-free chicken on the USDA procurement list.

Read More: Why So Many Childcare Centers Are Closing

Processors must meet the requirements from the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act to qualify to serve food, she says, but that doesn’t mean the food is necessarily healthy. “We’re more concentrated on meeting the requirements than we are on the quality of food, and that’s where things have to change,” says Wilson. For example, every child has to take a fruit or a vegetable with a meal, which creates waste.

Cleaning up the foods that come from USDA allocation is one way to help districts that can’t afford to do scratch cooking, Wilson says. Some districts are moving instead to “speed scratch,” which means they’re cooking some things in the district and combining it with healthier USDA processed food. Many find it much easier to use the procurement process because the specific nutritional value of the foods from industry is calculated in advance to meet USDA requirements. Otherwise, there’s a lot of labor required to make sure that meals are meeting the requirements.

Major federal obstacles to change

The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act helped a lot of districts improve, says Wilson, who was the USDA Deputy Under Secretary of Food, Nutrition, and Consumer Services in the Obama Administration. That’s because it forced districts, parents, and educators to be laser-focused on the nutritional value of what they were serving.

“School meals have been really good for a long time,” says Wilson. “A lot of school districts are even way ahead of the MAHA movement, and eliminated ingredients out of our products a long time ago.”

Still, federal changes since 2012 have weakened some of the standards of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act. The first Trump Administration delayed implementation of science-based nutrition standards that would have reduced sodium and sugar in school meals, says Meghan Maroney campaign manager for Federal Child Nutrition Programs at the Center for Science in the Public Interest. The Biden Administration then restored some of those standards, but they were not as stringent as they had been in the initial law. “There was a lot of conversation about the nanny state and too many regulations and giving power back to the local communities,” Maroney says. Districts are going to be required to restrict added sugars in breakfast and lunch by the 2027-2028 school year.

Read More: Why One Dietitian is Speaking Up for ‘Ultra-Processed’ Foods

The food industry will have to reformulate some of its products to meet those standards, but for districts to satisfy them without relying on industry, they’ll have to focus more on scratch cooking—an increasingly costly proposition.

That’s in part because of inflation; the cost of food, equipment, and labor keeps rising. But it’s also because federal reimbursement rates for school lunches have not kept pace with inflation. Right now, schools get reimbursed a little more than $4 per student by the federal government. Restaurants would struggle if diners paid that little for food.

“Because of reimbursement levels, most schools can’t compete with culinary restaurants or retail stores that start at $20 an hour,” says Bettina Applewhite, a registered dietitian who consults school districts to help them make the transition to scratch cooking.

The MAHA movement and Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. have not made much progress in changing school lunches so far—in part because school meals are run by the USDA, rather than HHS. But if the government really wants to change school lunches, it should probably start with the reimbursement rate, says Maroney.

“Removing ultra-processed foods is going to cost a lot of money,” she says. “In order to do that, there have to be significant investments in the reimbursement rates, training, culinary technical assistance, and funding.”

Soltanmorad, of Tahoe Truckee, says that the investment is worth it. The district could, she says, just serve a lot of pizza and make its kids happy, but that wouldn’t be good for their health or their nutritional education. Now, they’re learning how to nourish their bodies and eat well—skills they’ll take with them once they’ve graduated to be healthy adults.