The U.S. has long used the promotion of democracy overseas as a crucial form of “soft power,” not only to gain ideological influence in global geopolitics, but also to foster the emergence of political systems overseas that are compatible with American security and economic interests. President Trump’s proposed 2026 budget, however, contains more than $10 billion in cuts to funds and organizations that promote democracy abroad by, for example, monitoring elections, strengthening democratic political parties, and supporting civil society groups.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

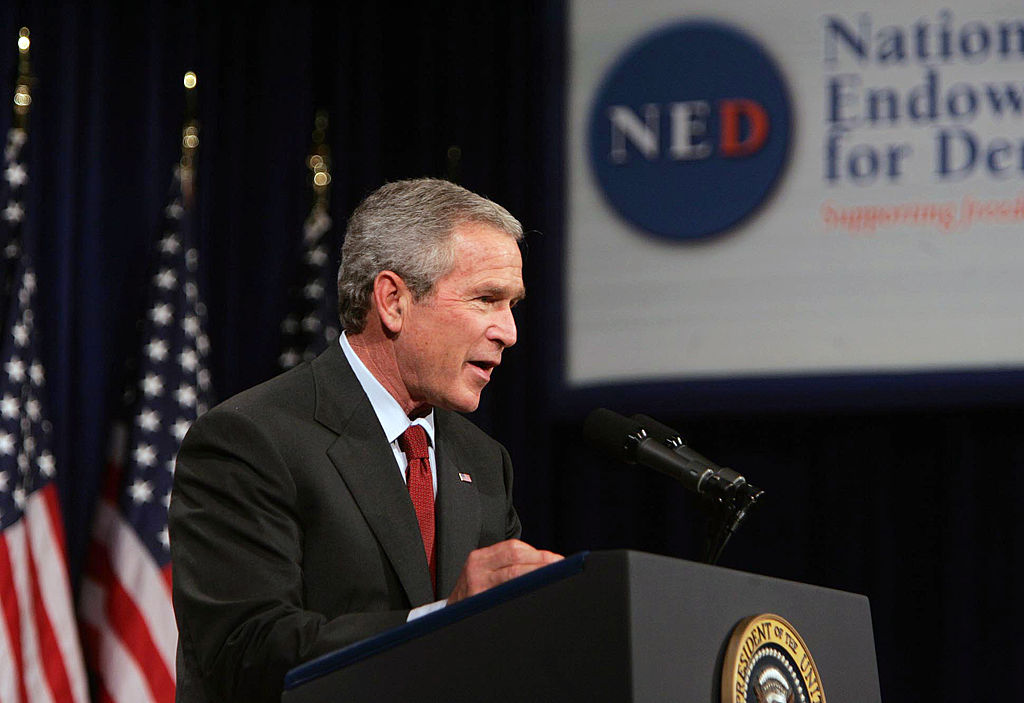

The most widely-publicized casualty is the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the largest single U.S. organization promoting democracy overseas, which the administration wants to merge into the State Department with 83% of its programs cancelled. Other democracy promotion engines—including the Democracy Fund and the Economic Support Fund—face severe cuts as well. One proposed budget cut that has received far less attention is the defunding of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED)—a non-governmental organization created during the Reagan Administration that has long enjoyed bipartisan support and receives almost all of its funding from an annual congressional appropriation.

These attacks signal the breakdown of bipartisan support for democracy promotion, which has existed for more than 75 years. It was first forged during the early Cold War when agencies like USAID were created—and subsequently ramped up in the final stages of the Cold War, when Democrats and Republicans alike hoped to undermine communism by creating the NED. Bipartisan support for promoting democracy abroad continued for decades after the Cold War ended. But now, Trump’s Republican Party has defected from this consensus. Now, the administration’s 2026 budget may mark the end of democracy promotion as a crucial component of U.S. foreign policy.

The history of the NED illustrates how far the Trump Administration has strayed from the long legacy of bipartisan support for promoting democracy abroad. In the early 1980s, a group of academics and officials from both parties argued that creating a U.S. organization to aid nonviolent democratic groups overseas could serve American interests. It would help prepare democratic movements to replace anti-communist (but also anti-democratic) dictatorships. If these regimes collapsed, democratic forces friendly to the U.S. could then step into power, containing more radical or Marxist opposition alternatives. Reagan Administration officials such as the President’s first secretary of state, Alexander Haig, championed the idea, arguing that it promised an additional benefit: support for democratic groups in communist states would disrupt Soviet expansionism.

More broadly, the creation of the NED was compatible with the Reagan Administration’s governance approach of prioritizing markets, deregulation, and privatization. Like President Reagan, those pushing for democracy promotion equated political freedom with strengthening free markets and thereby lessening the attraction abroad to movements—including but not limited to communism—that aimed to redistribute resources to reduce economic inequality. The fact that supporters of democracy promotion aimed to foster the emergence of democracy through strengthening non-state actors, rather than through aid to foreign governments, fitted with Reagan’s own small-government preferences.

Read More: How Trump’s USAID Freeze Threatens Global Democracy

However, initially, conservatives weren’t all on board. Some Reagan national security aides feared that a democracy-promotion organization could undermine anti-communist geopolitical relationships crucial to containing Soviet influence in the Third World if it supported foreign democratic forces critical of dictators allied with the U.S. Meanwhile, liberal Democrats in Congress pushed for an even-handed campaign for democracy that would target dictatorships of the left, including those in Communist Poland and Sandinista-controlled Nicaragua, and the right, such as military regimes in Chile and Pakistan, as well as apartheid South Africa.

In 1983, Congress attempted to forge a compromise when it created the National Endowment for Democracy. The NED’s non-governmental status meant that the administration could disclaim responsibility for its actions, thus avoiding damage to diplomatic relations with its undemocratic anti-communist allies. Meanwhile, the NED’s distance from day-to-day administration policy empowered it to take a global approach focused on dictatorships of the right and left.

The NED went on to support anti-communist forces in leftist authoritarian states aligned with the USSR, including in Poland and Nicaragua. Yet, it also supported pro-U.S. democratic forces in countries with right-wing authoritarian rulers who were American allies and who faced Marxist opposition movements, such as the Philippines and Chile. All of these efforts stemmed from the belief that democratic societies based on free markets would create politically stable and prosperous societies.

The end of the Cold War helped usher in crucial shifts that entrenched democracy promotion as a long-running, bipartisan element of U.S. foreign policy. American policymakers and elites widely interpreted the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union between 1989 and 1991 as an “end of history.” Under this thinking, liberal democratic capitalism was the last political and economic model standing after the global struggles of the 20th century—and, consequently, the inevitable final political form for every other society on Earth. Strategically, the demise of America’s Soviet rival led to the creation of a unipolar world in which the U.S. faced fewer geopolitical constraints in promoting its favored political model.

This ideological and strategic convergence was strengthened by the emergence of a consensus around Reagan’s deregulatory economic philosophy and faith in free markets in both major American parties in the 1990s. When Bill Clinton’s “new Democrats” came to power in 1993, they adopted core elements of Reaganism, such as its emphasis on small government, equation of freedom and free markets, and desire for deregulating business. These convergences resulted in a Clinton-era foreign policy that aimed to promote the spread of “market democracies,” which combined a focus on liberal political institutions with Reaganite economic policies—all predicated on the notion of American hegemony in an increasingly globally-connected world. This led the administration to expand democracy promotion and bring it in-house by integrating it into USAID and the State Department, while the NED continued to operate independently.

The entrenched bipartisan support for democracy promotion was predicated upon a calculation that linked neoliberal governance, liberal democracy, and U.S. foreign policy interests.

Read More: Inside the Chaos, Confusion, and Heartbreak of Trump’s Foreign-Aid Freeze

The bipartisan emphasis on democracy promotion does not mean that it has been the basis of all U.S. foreign policy since the Cold War. Rather, the U.S. has supported autocracies—including in Saudi Arabia and in authoritarian Central Asian states, such as Uzbekistan—when policymakers believed that doing so was useful to achieve short-term U.S. national security interests.

Nevertheless, democracy promotion has persisted alongside these tactical policies as a long-term project to create a world full of states similar to the U.S. and open to its hegemonic economic influence. The George W. Bush, Obama, and Biden administrations continued to strongly support–and fund–these priorities through the War on Terror and the more recent framing of foreign policy as a contest between U.S.-led democracies versus autocratic states, particularly Russia and China.

President Trump’s MAGA movement, however, has defected from this post-Cold War consensus, opening the door to dismantling organizations like USAID and NED. This new direction appears to be driven by a focus on non-interventionism overseas, unless deemed necessary to protect immediate and tangible American interests, and a skepticism of efforts to promote political change in other states. During a commencement address at the Naval Academy, Vice President J.D. Vance lamented how the U.S. had “traded national defense and the maintenance of our alliances for nation building and meddling in foreign countries’ affairs.”

Instead of democracy promotion, the Administration is pursuing diplomacy with states irrespective of their form of government—rather than on trying to alter or reform foreign political regimes to bring them in line with the U.S. model.

It is unclear whether Trump’s dismantling of the democracy-promotion organizations will be successful. Much depends on the dynamics of Congress and the Republican Party.

However, two key shifts are clear. First, Trump’s approach to democracy promotion signals a broader transition in American foreign policy away from deploying soft power and toward increasingly relying on military and economic coercion. This impulse includes narrowing the definition of human rights and shrinking or eliminating foreign aid. Second, the decades-long, domestic bipartisan support for promoting U.S. democracy abroad—which created and sustained organizations like the NED—has now seemingly been replaced with calls for “America First.”

Robert Pee is the author of Democracy Promotion, National Security and Strategy: Foreign Policy under the Reagan Administration, co-editor of The Reagan Administration, the Cold War, and the Transition to Democracy Promotion, and has had his work published in journals such as Cold War Studies and Diplomacy & Statecraft.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.