Last month, the White House alerted the Smithsonian Institution that the exhibits of eight of its museums were now subject to a White House committee’s review and oversight. This action followed an April executive order from President Donald Trump titled “Restoring Truth and Sanity to Our American History,” that emphasized a positive view of history in the form of “uplifting public monuments that remind Americans of our extraordinary heritage.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

While it’s unclear how the White House team would replace or edit content, they have expressed their distaste for “divisive” and “partisan” history in favor of an American history that is “exceptional” and “uplifting,” one that “unifies” its citizens and emphasizes “progress.”

In a much more modest house—a tenement on New York City’s Lower East Side—we see every day how American history can be both ordinary and exceptional, complex and communal, diverse and unifying.

We saw this beautiful complexity in action this summer, when 45 elementary, middle and high school teachers from 29 states across the country gathered at the Tenement Museum for a week-long intensive on teaching immigration history and Black history. Historians guided the teachers through an immersive journey into the 19th and 20th centuries, tracing how Irish, German, Black, Jewish, Italian, Puerto Rican, and Chinese New Yorkers navigated the Civil War, Reconstruction Amendments, the Chinese Exclusion Act, industrialization and the conditions and politics of their days.

We did not discuss the Washington politics of our own days, as the teachers—regardless of where they came from—came together to study history. But by the end of the week, their reflections on the role of history in the classroom and community constituted a powerful demonstration of how we can protect and honor American history.

Lesson 1: The ordinary is extraordinary

Whereas most textbooks highlight the famous, we must also focus on those who never imagined being remembered, much less featured in a museum. Most Americans descend from those with humble beginnings; standing in our kitchens, hallways, and stoops, visitors often imagine their ancestors in these spaces. As one teacher noted, powerful history doesn’t have to come from figures in whose memory monuments have been built, but from the everyday people and family members who represent Americans as a whole.

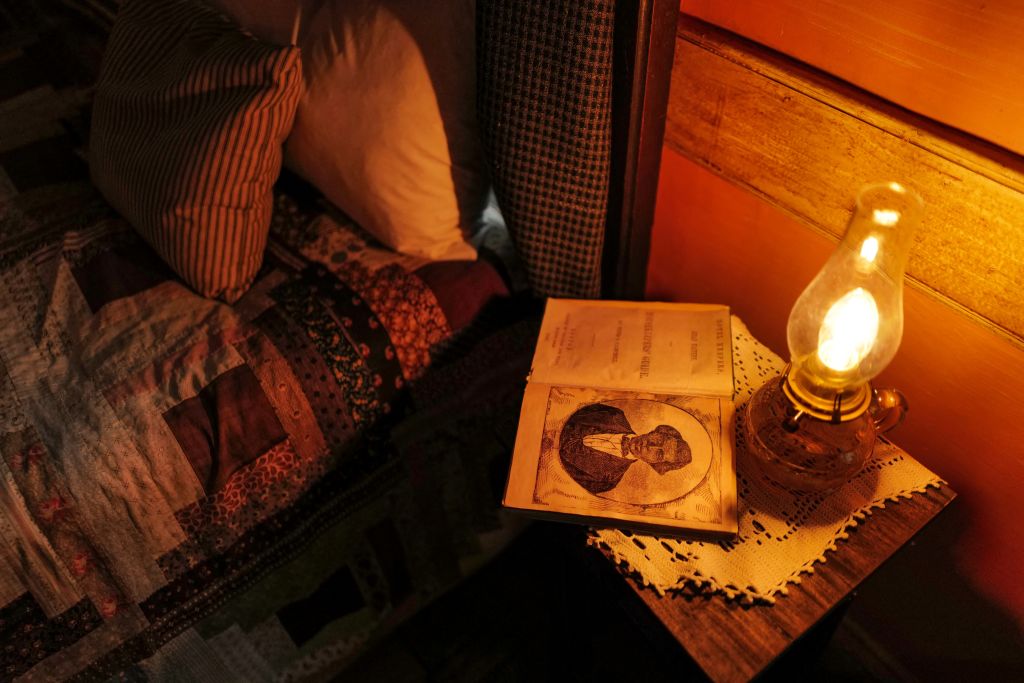

Teachers gravitated to a book in one of our exhibits, Sermons and Addresses by Abraham Lincoln, that originally belonged to Parthenia Lawrence, a Black teenager who lived in the tenements during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Considering this book in the hands of a 14-year-old who attended a segregated school in 1860s New York, the teachers explained, students could respond to the political history within the text, and could also imagine and consider how those speeches were absorbed, debated and reflected upon by ordinary people. Approaching history from multiple perspectives makes it come alive, enabling students to more directly engage with the dynamic and evolving meanings of freedom, literacy and citizenship.

Lesson #2: Americans progress through struggle and the formation of community

The past is not always pretty, especially when viewed from the tenements and the daily life of ordinary people. There is no question that the study of history and its conflicts, injustices and exclusions can be dispiriting. The Civil War unfolded in battlefields, but also wrought the Draft Riots in New York City, during which dozens of Black residents were murdered, property was destroyed, and the city terrified. Economic downturns such as the Panic of 1873 and the Great Depression disproportionately affected the working class, immigrant neighborhoods, sparking unemployment and the dissolution of families. The lack of regulation of factories led to horrific workplace accidents, and the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire claimed 146 victims, mostly Italian and Jewish young women.

Even as tragedy and struggle beset the tenement districts, the very qualities that defined the tenement’s unfavorable physical conditions—over-crowdedness and density—became building blocks for community. Tenement dwellers established mutual aid societies, churches, synagogues, fraternal clubs, labor unions, literary societies, political clubs, many of which adopted American “constitutions” and rules of order.

More broadly, tenement dwellers exercised their freedom of assembly, press and speech by publishing and reading newspapers, and delivering and listening to speeches. They gathered in Cooper Union’s Great Hall to celebrate the passage of the 15th Amendment, protest corruption in City Hall, call for an end to the Chinese Exclusion Law, and demand workers’ rights. They united to protest, to celebrate, and to create change.

In the wake of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, politicians, reformers, and downtown activists formed the Factory Investigation Commission, which led to state and ultimately national improvements in workers’ safety and health. In many of these examples, a shared recognition of injustice—or as one teacher put it, “the gap between American ideals and reality”—brought together people of diverse backgrounds to mobilize for change. It wasn’t about where they had come from, or which neighborhood they lived in, but rather how they wanted the country to advance that united people. As another teacher put it, “we aren’t perfect but we want to be better. That is what it means to be an American.”

Lesson #3: Difficult family histories can teach us resilience

The Emory University psychologists, Dr. Marshall Duke and Dr. Robyn Feivush, coined the term the “intergenerational self” to refer to the sense of expanded and protective identity that develops in students who know their own family histories. They found that students who knew a history of ups and downs proved more resilient. If we know that our ancestors encountered difficult times, the very fact that there’s a story to inherit and transmit means that the family moved forward. In turn, the knowledge that our own families encountered setbacks and persevered provides strength and resolve when we encounter challenges in the present.

Teachers intuited the connection between struggles and progress in families, and within history, and felt that the teaching of a complex history, one that did not sugarcoat the struggles, would build a more resilient classroom, community, and country. One teacher reflected on how her time in a tenement, and its tiles, banister, and odors, sparked memories of her own family home and how that offered her strength that she wished to confer to her students.

In a charged political climate, one in which “history” has made headlines and even certain basic vocabulary has been called into question, people of various backgrounds and identifications can still form a community.Republicans and Democrats alike comprehend that history can be complicated, and it is OK at times to recognize that new insights on history can challenge elements of previous understandings.

History cannot be truly unifying unless we learn of past divisions, conflicts and struggles; we cannot understand uplift without noting despair, and we cannot make progress without identifying the gaps between American ideals and reality.