Zen Honeycutt and droves of other supporters of the “Make America Healthy Again” movement cast their votes for President Donald Trump last year after hearing the promises that he and Robert F. Kennedy Jr., now the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, made about cracking down on pesticides and chemicals in food.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

“Many people voted for Trump because he talked about pesticides and chronic diseases in the same sentence on the campaign trail,” says Honeycutt, the founder and executive director of Moms Across America, a group linked to the MAHA movement. “It was historic. Millions of mothers and fathers heard that and we cheered and cried. We thought, ‘They’re actually going to do something about pesticides in the food supply.’”

But as the Administration has floundered in making real progress on these issues—and some Republicans in Congress push back against their agenda—MAHA supporters are voicing their frustration, and with it, a threat to take their votes elsewhere.

“We will not ‘Make America Healthy Again’ if we don’t get toxins out of the food supply,” says Honeycutt, a close ally of Kennedy’s. “I am adamant, and I am speaking up. At this point, I do not care if it ruffles feathers.”

Honeycutt and other “MAHA moms” were disappointed by the MAHA commission report released in September that they say lacked meaningful regulatory action on pesticides and ultra-processed foods and watered down earlier proposals to overhaul the food system.

They say they are also dismayed by the Trump Administration’s moves to speed up pesticide approvals and Republicans’ support for a new proposal that they say would protect pesticide

companies from consumer lawsuits.

Kelly Ryerson, a MAHA supporter and advocate for pesticide regulation, says she has been surprised that more Republican lawmakers haven’t embraced MAHA’s food-related priorities. “They haven’t woken up to the fact that this is a really important issue to a lot of Republican voters. It’s going to be a big problem for them in the midterms,” she says.

A fight over pesticide legislation

A majority of American voters said in an August poll that they were aware of MAHA. Among Republican respondents aware of MAHA, most viewed the movement favorably, and some 90% said the movement reflected their values about food and agriculture.

But issues related to food-system reform have exposed potential incompatibilities between MAHA and leaders of the Republican Party, which has long been aligned with the food and agricultural industries, food-policy experts say. Some Democrats say they see this as an opportunity for their party to engage with the MAHA movement on issues that have historically been the domain of the left.

“It’s a convergence of ideas,” says Rep. Chellie Pingree, a Democrat from Maine. “I’ve been talking to many of my colleagues about this. Don’t miss this opportunity. Let’s find areas where we can find a win, like healthy food or [pesticides].”

Pingree, an organic farmer, led a recent push in the House to strike a provision from a government spending bill that critics say would shield pesticide manufacturers from liability.

The pesticide rider, which Republicans tucked inside the House version of a spending bill that would fund the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Interior Department for the next fiscal year, would bar the EPA from approving language on pesticide warning labels that are inconsistent with the agency’s own human health assessments.

Critics say this is potentially dangerous because the EPA’s assessments are outdated and the provision would effectively block state and local governments—many of whom have included more stringent standards and warnings on pesticide labels than what the EPA requires—from being able to adequately regulate pesticides in their own jurisdictions.

The provision would also make it harder for people to sue pesticide manufacturers over alleged health harms, critics say, as such lawsuits often rely on evidence that the companies didn’t sufficiently warn consumers about the potential risks of their products. If limits are placed on what can be included on pesticide warning labels, courts could conclude that pesticide manufacturers aren’t to blame for failing to warn consumers, critics say.

Read More: Is Beef Tallow Actually Good for You?

The EPA, for instance, doesn’t classify glyphosate, a widely-used herbicide sold under the brand name Roundup, as a carcinogen. The World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded in 2015 that the herbicide was “probably carcinogenic”. A study published in June found that rats exposed to low doses of glyphosate and glyphosate-based herbicides were more likely to develop different kinds of cancer than rats that weren’t.

As an environmental lawyer, Kennedy in 2018 helped a former school groundskeeper who had developed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma to successfully sue Monsanto, the maker of Roundup, for failing to warn consumers about the possible health risks from glyphosate exposure. Chemical giant Bayer merged with Monsanto that same year. Bayer has since agreed to pay out more than $12 billion to resolve tens of thousands of lawsuits alleging health harms from Roundup exposure.

The spending bill rider would protect the company from these types of lawsuits, says David Murphy, a former fundraiser for Kennedy’s presidential campaign and an advocate for pesticide regulation. Bayer has lobbied hard for similar provisions both at the federal and state levels, the New York Times reported. “Bayer is desperate,” Murphy says.

Bayer said in a statement to TIME that it stands behind the safety of its glyphosate-based products. “We agree that no company should have blanket immunity and, to be clear, the language in [the spending bill] would not prevent anyone from suing pesticide manufacturers,” a Bayer spokesperson said. “Legislation at a federal level is needed to ensure that states and courts do not take a position or action regarding product labels at odds with congressional intent, federal law and established scientific research and federal authority.”

Pingree’s effort to remove the provision from the spending bill met with support from most Democrats in the House Committee on Appropriations, but no Republican in the committee backed the amendment. The provision remains in the bill.

Speaking in support of the rider, Rep. Mike Simpson, a Republican from Idaho, told the committee that members of the MAHA movement had been vocal in their opposition to the provision but said they were confused about what it actually does.

“I know the MAHA moms have been calling,” Simpson said during a committee meeting in July. “I think we ought to make America healthy again, I’m glad they’re taking an active role in this but they’re getting so much misinformation about what this does.”

Simpson says the provision would have very limited impact. His office said in a statement that the purpose of the rider is to “prevent a patchwork of state labeling standards by requiring the standard be a federal standard, so it’s to prevent a single state from setting labeling standards for the rest of the country.”

Vani Hari, a prominent MAHA influencer known by her online moniker “Food Babe,” says Simpson should be concerned about the future of his House seat.

“The entire MAHA movement is very aligned in making sure that this pesticide liability [rider] doesn’t happen. Republicans or Democrats who vote for it are going to have a rude awakening in 2026,” she says.

Republicans are expected to include similar language as the spending bill rider to the new Farm Bill. The language would also limit pesticide injury lawsuits, the New Lede reported.

Read More: Seed Oils Don’t Deserve Their Bad Reputation

Honeycutt of Moms Across America says she and other MAHA supporters were in D.C. in mid-September to urge members of Congress to reject the pesticide rider and any similar legislation that would protect pesticide makers from liability. Democratic lawmakers were more receptive across the board to their message, Honeycutt says, while the offices of many Republican lawmakers echoed talking points pushed by the pesticide manufacturers.

Honeycutt says she and other MAHA supporters are actively looking for a Republican cosponsor for the Pesticide Injury Accountability Act, a bill introduced in July by Sen. Cory Booker, a Democrat from New Jersey, that would protect consumers’ ability to sue companies in federal court for harms caused by agricultural chemicals.

“Nobody has stepped up yet. We are looking for leadership,” Honeycutt says. “We want to be able to continue to have the MAHA movement be bipartisan.”

In the press release announcing the pesticide bill, Booker’s office quoted several people and organizations affiliated with Kennedy and MAHA who support the legislation. They included Honeycutt, Ryerson, and Children’s Health Defense, an antivaccine group founded by Kennedy.

“This is a big opportunity for Democrats to bring MAHA groups into existing coalitions,” says a longtime Democratic aide who asked to speak anonymously to discuss a politically sensitive issue.

As for Republicans, “it’s a losing issue for them to lock onto the pesticide industry’s talking points,” says Murphy, the former Kennedy fundraiser.

Unhappiness with MAHA’s action plan

Murphy, who founded the food-system reform organization United We Eat, says he was disappointed by the recent MAHA commission strategy report, which he says pulled punches on core MAHA issues including pesticides and ultra-processed foods. Unlike the commission’s first report released in May, which linked exposure to agricultural chemicals like glyphosate to health harms including cancer and developmental disorders such as autism, the new report didn’t mention glyphosate by name, nor did it suggest any action to restrict pesticide and herbicide use.

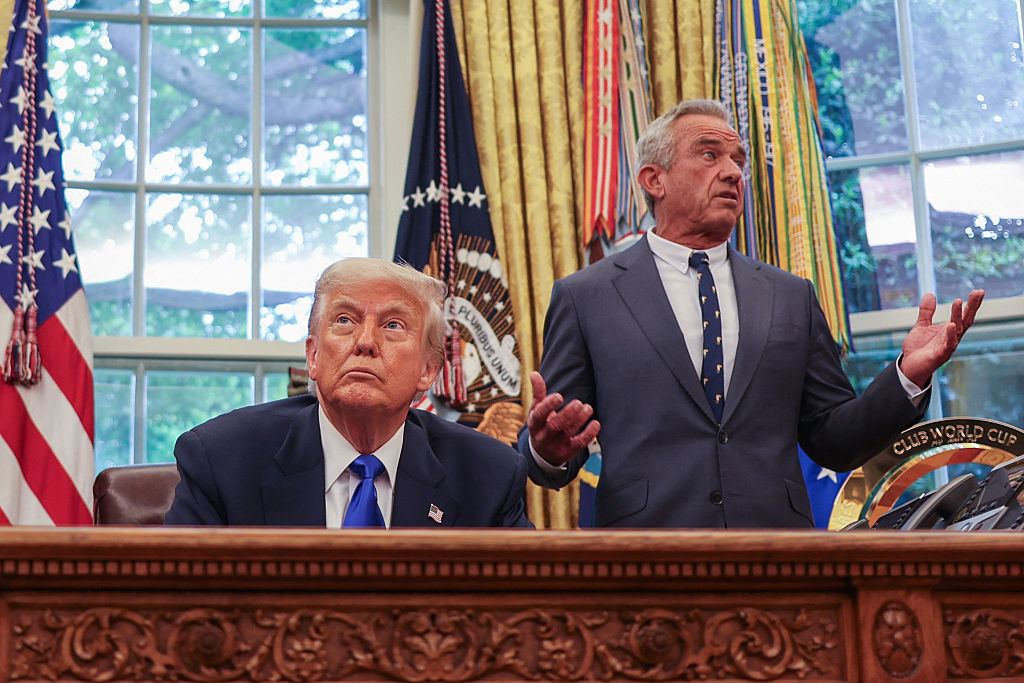

On Sep. 22, Trump, flanked by Kennedy and other federal health officials, announced at a White House briefing that his Administration was launching an effort to address the “horrible, horrible crisis” of autism. Kennedy and other officials laid out their plan to probe possible causes, including vaccines. (Decades of research does not support a link.) Pesticides, some of which have in preliminary studies been associated with autism, weren’t mentioned during the briefing.

Honeycutt says MAHA supporters were thrilled that the Administration addressed “some of the causes of autism” and says they “expect pesticides to be addressed in the future.”

Read More: A Battle Is Brewing Over Whole Milk

“There are mountains of evidence already showing a connection to autism with glyphosate exposure. Whether this Administration acknowledges this factor, and takes action, could mean a difference between millions of children being harmed, or not,” Honeycutt says.

The MAHA strategy report didn’t recommend stricter regulation of pesticides. Instead, it endorsed the government’s existing pesticide review process, calling it “robust”—echoing language that the pesticide industry had itself recommended to the commission. The report also said that the EPA would “work to reform the approval process” for pesticides, though it didn’t specify what that would entail. Lee Zeldin, the head of the EPA, has said the agency—which has come under scrutiny for hiring three chemical industry lobbyists to critical roles in its chemicals office—is expediting the review process for pesticides. In recent months, the EPA has approved four pesticide ingredients that the Center for Biological Diversity says are PFAS, or perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances—“forever chemicals” that could threaten peoples’ health. “It’s just a sign of how powerful the pesticide industry is,” Murphy says.

Food and agriculture sectors relieved

Lobbyists for the food and agricultural industries say they pushed hard for changes in the second MAHA report.

Senior White House officials were taken aback by the anger expressed by farmers and others in the agricultural sector after the first report was released, according to lobbyists who worked with companies and groups involved in some of these discussions and who spoke on the condition of anonymity. The officials encouraged the report’s lead authors including Calley Means, a top aide of Kennedy’s, to take a different approach for the second report and to engage with farmers and others in the food industry, the lobbyists say. Means did not respond to requests for comment.

Over the summer, the White House invited dozens of groups and companies from the food industry to discuss the first MAHA report.

“Farm groups were very, very mad after the first report. They felt betrayed. I give the Administration a ton of credit. They realized they made a mistake and opened the door,” says the head of a leading agricultural trade association. “During the second process, they flipped.”

A narrow shot at real food-system reform

Given the apparent influence of industry on the second MAHA report, Marion Nestle, a professor emerita of nutrition, food studies, and public health at New York University, says she isn’t hopeful that Kennedy and his supporters will accomplish meaningful food-system reform.

“MAHA cannot achieve what it says it wants to achieve because it will go against industry interest. We’ve already seen RFK Jr. back off on agricultural chemicals and ultra-processed foods. There’s nothing new there,” Nestle says. “Think about Michelle Obama’s ‘Get Moving’ campaign. It doesn’t look at all different from this. It made the same kinds of recommendations, and it was greeted with total opposition.”

Many of Kennedy’s supporters remain optimistic, however. They say Kennedy’s efforts to make real change to the food industry have been hamstrung by others in the Administration, but that he should be congratulated for kickstarting a national conversation about these issues.

“I have never seen this type of awakening within our country ever before,” says Hari, the MAHA influencer. “These issues used to be seen as Democratic issues or hippie issues, but the other side of the country has awakened to this idea that our food is being poisoned with chemicals.”

Both MAHA reports were revolutionary in their attempts to tackle food-system reform on a national scale, supporters say. Ryerson, the pesticide-regulation activist, says that even though pesticides weren’t as explicitly called out in the second report as she would have liked, it was alluded to “between the lines” in sections about soil health, for example. She sees Kennedy’s fingerprints all over the report.

Ryerson, who has a large social-media following as the Glyphosate Girl, says she has been heartened by steps taken by HHS to encourage the food industry to voluntarily stop using synthetic food dyes. She is also hopeful that Kennedy will be successful in reforming the “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) loophole, which has allowed food manufacturers to introduce new additives without U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval.

Kennedy’s moves related to vaccines have also kept many MAHA supporters happy. “The MAHA movement is mostly fueled by parents who are motivated to create medical freedom and also access to nontoxic, nutrient-dense food,” Honeycutt says, adding that she hopes Kennedy and the Trump Administration will not just focus on food-system reform but will also make vaccine mandates illegal.

Read More: Why It’s So Hard to Make School Lunches Healthier

As the head of HHS—which oversees the FDA, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the U.S. National Institutes of Health—Kennedy has more authority over vaccine research and policymaking than over food and agriculture, which also fall under the purview of other agencies, food-policy experts say.

But Kennedy still could have an impact on food. The FDA could set a standard for how much of a certain additive or chemical, including pesticides, are contained in foods, says Nestle, the former NYU professor. “They could declare foods that have any of these things as adulterated, and they would be removed from the market immediately. That could happen today.”

The FDA could also require complete transparency on food labels or warning labels on food like those required in Mexico and Chile, which flag products that contain high levels of sugar, sodium, and saturated fat, Nestle says. The NIH could earmark funding for studies on nutrition and the risks of exposure to pesticides, additives, and other chemicals.

Regardless of what Kennedy himself achieves, the MAHA movement has laid bare a fundamental bipartisan shift in how people now think about health and food, supporters of the movement say.

“It is definitely an issue that has reached a tipping point,” says Ryerson. “Democrats have arrogantly assumed this was their issue. Now Republicans are going to be called to step up.”