Tensions are once again rising in Somalia. The East African country has been mired in civil strife ever since the central government collapsed in 1991 following a series of uprisings against the then-military dictatorship. Successive Somali national governments have tried ever since to build up the state’s capacity, strengthen democracy, and extend its territorial control. But none of them have managed to temper bruising, deadly fights over power and resources.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Now, the current administration led by President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud is gearing up for national elections in 2026 by pushing through controversial plans to change the electoral model that it says are necessary to improve the system. But opposition politicians as well as the statelets of Puntland and Jubaland counter that these plans are designed to bolster Mohamud’s re-election and extend his time in office. The dispute is causing paralysis and threatening to spill over into violence.

At the same time, notorious Islamist groups are on the offensive. Al-Shabaab, an Islamist insurgent group that has battled the central government for two decades in southern and central Somalia, is gaining ground. As is the Islamic State. (Though the latter has suffered major losses in recent months following a campaign by Putland forces backed by drone strikes from the UAE and U.S.)

Against this backdrop, the foreign donors who have sustained one of the world’s oldest state building projects, are growing impatient.

The vote impasse

The dispute over elections that are due by May hangs over Somalia. Mohamud wants to scrap the current system, which in 2021 saw a mere 28,000 voters in a country of 15 million choose the country’s politicians. He is aiming to ditch the indirect voting system led by clan leaders in favor of universal suffrage.

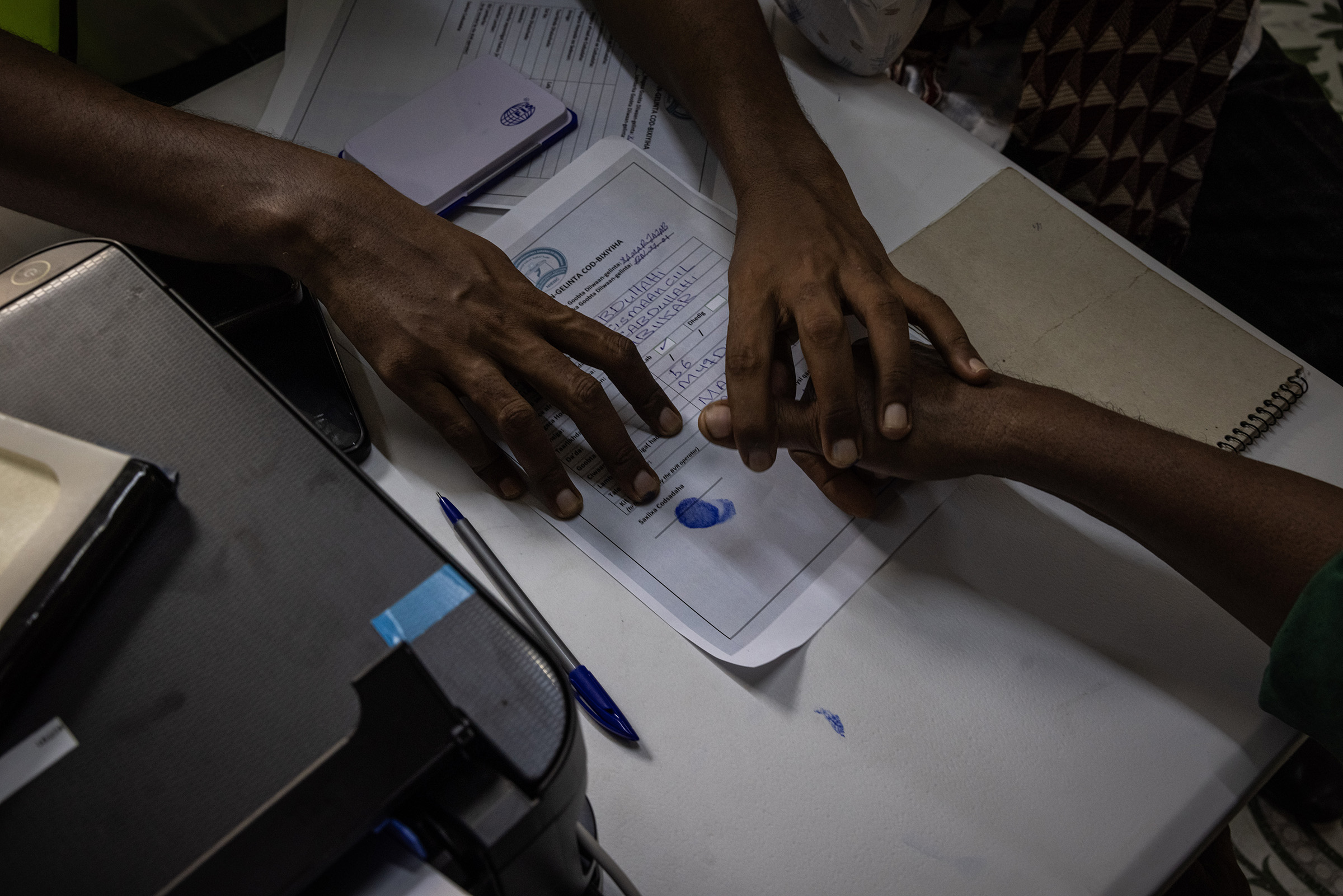

Strengthening democratic participation, which the central government argues it is pursuing, is a laudable ambition. It has already established an electoral commission and has begun to register voters. But time is running out and many observers argue that the only practical way to hold timely elections is to keep the indirect election system. Indeed, the previous president, Mohamed Abdullahi Farmaajo, stayed in office for an extra 15 months when the last election in 2021 was not held on time.

The dispute has largely remained peaceful so far. But both sides are increasingly jumpy in the capital Mogadishu—two were killed in late September after rival security units clashed following a visit by opposition politicians to a local police station.

Political obstacles

The electoral dispute highlights Somalia’s ongoing political dilemmas. The central government has struggled to function effectively since it was created in 2012, with U.S. backing, to replace a series of shaky transitional governments. Yet over a decade later, the constitution remains provisional and there is no clear agreement on how the central government in Mogadishu shares power with Somalia’s seven member states—some of which operate fairly autonomously.

Some of the more assertive states, including Puntland in the north and Jubaland in the south, have effectively withdrawn from Somalia’s federal system. Tensions between Mogadishu and the latter even flared into a violent clash near the Kenyan border in December, following a dispute over the re-election of Sheikh Ahmed Madobe, the statelet’s leader and a current nemesis of Mohamud. Both sides are now jostling for control of Jubaland’s northern Gedo region.

These chronic internal divisions have hindered Somalia’s ability to tackle some of its most intractable problems, whether these are the fight against Al-Shabaab, adapting to the protracted droughts brought on by climate change, spurring economic development, or finalizing the constitution.

Meanwhile, Somalia is grappling with a fundamentally different aid landscape. The central government relies on foreign assistance for two-thirds of its budget, and the African Union’s peacekeeping mission props up its security. The Trump Administration has slashed aid from $750 million in 2024 to $150 million this year.

Somalia has diversified its external support in recent years, deepening ties with Türkiye and some Gulf states, but it is struggling to make up for a substantial decline in Western aid.

The search for solutions

Not all is doom and gloom. The central government has largely driven Al-Shabaab out of urban centers, enabling an economic resurgence, particularly in Mogadishu, where new high-rise buildings are sprouting across the capital. That has allowed it to establish the building blocks of the federal state, including national and local ministries. Violence still occurs in Mogadishu—Al-Shabaab raided a prison complex earlier this month, for example, and has made multiple attempts on Mohamud’s life—but the frequency of large-scale incidents has declined significantly.

No one wants to see these gains reversed. Somalia’s various political leaders urgently need to demonstrate to the international community that their state-building project remains worthy of investment. In the short-term, this means coming to a compromise on the electoral system, and holding polls in a timely fashion next year.

In the longer term, politicians need to make the federal system work better. This would require clearly setting out which powers should be at the national level, which are reserved for the states, and how the two levels of government should interact. Reinstating regular meetings between Mogadishu and member states would be a useful first step, but this will still need to be followed by a great deal of pragmatism and compromise on both sides.

Resolving these sources of tension will help the federal system to function more effectively, reverse the tide of political fragmentation, and enable a more unified response to the many shared challenges. Somalia’s political leadership, both the government and opposition, needs to move the country forward.

Failing to do so will mean more division, donor disillusionment, and opportunities for Al-Shabaab. And it is ordinary Somalians, after all, who would pay the price.