Just before my 25th birthday, I hooked my feet into stirrups on an icy exam table, ready for a doctor to retrieve my eggs. I’d been diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma and learned chemotherapy might make me infertile. Cryopreservation, or egg freezing, was a way to help me become pregnant through IVF if I survived.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

At the time, nearly seven years ago, my health insurance wouldn’t cover the procedure, despite about 2% of babies in the U.S. being conceived by IVF. My family and I managed to cover the more than $12,000 in out-of-pocket costs, but it was a stretch.

So I felt hopeful when, on Oct. 16, the President announced his plan to usher in a generation of “Trump Babies” through proposals to make IVF more accessible. Given his campaign promises to make the procedure free and require insurance coverage, I expected a plan I could get behind: IVF access for all through insurance mandates and Medicaid coverage. My hope was quickly quashed.

While it’s true the proposal will lower the cost of key IVF drugs by up to 84 percent—and encourage employers to offer IVF, it’s an overall letdown. The lack of a public insurance option will exclude millions, given that in 2024, 17.6% of Americans were on Medicaid. The plan also doesn’t include the long-promised insurance mandate, which could guarantee IVF access at the federal level for often left-out groups: single people, same-sex couples, and those with chronic diseases that threaten fertility. Without a federal IVF standard, these would-be parents are left to navigate a scattered patchwork of state laws.

Far from igniting a baby boom, the White House plan will only slightly decrease costs and fail people who most need IVF to grow their families.

Read more: The Real Way to Boost Birth Rates

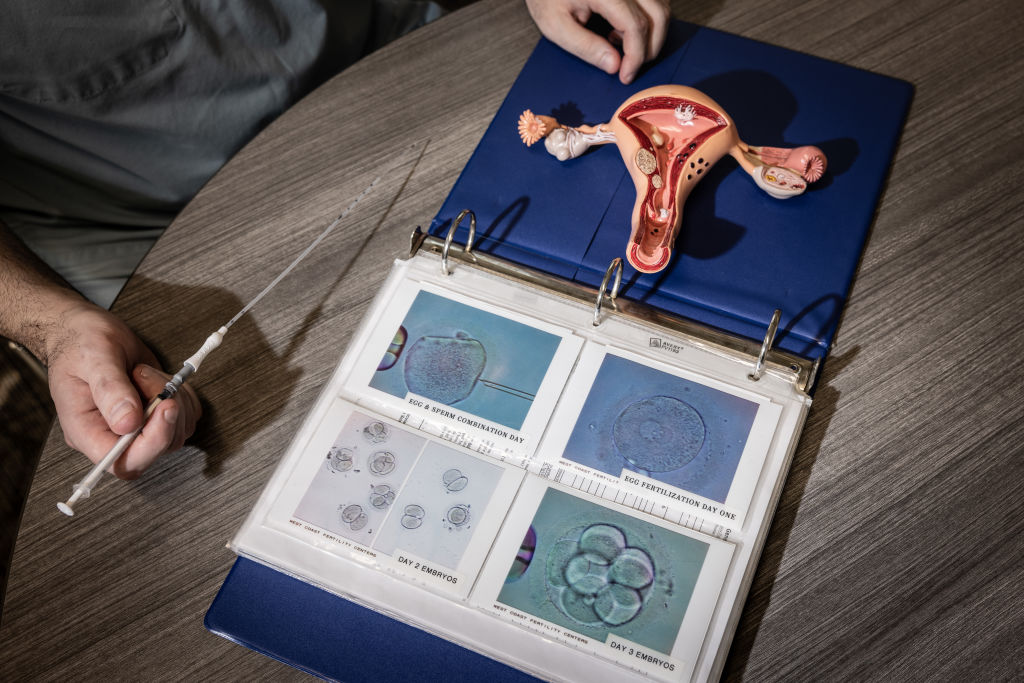

No wonder countries such as Denmark, Greece, and Spain have seen a boost in fertility tourism over the last decade. Cost is a key reason. In the United States, one cycle of cryopreservation can cost more than $20,000, while egg storage can exceed $1,000 a year. Then there are the multiple lab visits, the egg retrieval process, the fertilization of oocytes, and the embryo transfer or implantation fees, none of which will be impacted by reduced drug prices under the White House IVF proposal. Further, many patients require multiple rounds of IVF, hiking up costs. After six cycles, only two-thirds of women become pregnant on average.

Meanwhile, in Barbados, one of the more popular fertility destinations from the U.S., the total cost for a cycle of IVF without an egg donor ranges from $4,600-$6,400, and the cost of cryopreservation—which put me out $12,000—is just $4,000. Costs are even lower for IVF in some European destinations. Even including airfare and accommodations, the total comes in at less than an IVF cycle in the U.S.

Because most U.S. insurers don’t cover fertility care, many Americans pay the steep costs of IVF out of pocket. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine estimates that fewer than a quarter of infertile couples have access to treatment. As of April 2025, only 22 states and Washington, D.C., require insurers to cover fertility care—and just 15 include IVF. Only eight states require Medicaid to cover infertility treatment or cryopreservation. That leaves the unemployed, gig workers, and those on Medicaid or in small businesses largely unprotected.

The new federal IVF proposal merely encourages companies to offer standalone fertility benefits, like dental or vision coverage, without requiring or subsidizing them. Unsurprisingly, only a quarter of large employers currently cover IVF, despite infertility affecting 11 percent of women and 9 percent of men. Encouragement without incentives is unlikely to change that.

Elsewhere, fertility care is far more accessible. About 64 percent of countries offer public insurance or subsidies for IVF. Israel funds it until a woman has two children; all EU nations now provide publicly funded options; and in Denmark where the laws are liberal and inclusive, around 10 percent of babies are conceived via assisted reproduction.

In the U.S., access depends on where you live and who you are. Definitions of infertility vary, and some states exclude same-sex couples, single people, or those seeking egg freezing for genetic or gender-affirming reasons. People at risk of infertility from diseases like cancer or polycystic ovarian syndrome rarely qualify for coverage. Without a federal mandate, these inequities will persist.

Abroad, restrictions on IVF access exist but are generally looser, costs are lower, and public coverage is broader. Even Canada, where IVF isn’t universally covered, helps offset costs through its Medical Expense Tax Credit, expanded in 2022 to include fertility expenses.

The White House deserves credit for backing IVF, despite right-wing opposition equating embryo disposal with abortion. But the plan falls short. Expanding access only makes sense alongside broader supports like paid leave, livable wages, and affordable childcare that make parenthood sustainable. Meanwhile, the administration is cutting research and health subsidies, which will raise costs and further limit IVF access, especially for Medicaid recipients.

If the U.S. truly wants to encourage reproduction, it should follow the lead of countries with more inclusive and affordable fertility policies. Until then, Americans will keep seeking IVF abroad.