For decades, I was fascinated with Vice President Dick Cheney. The day I finally got to meet him in his St. Michael’s, Maryland weekend home in 2010 was a dream come true for me.

His house at the end of the gray gravel road was off-white. It was at once a page ripped from a William and Sonoma catalogue and still mismatched.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

The owners, Dick and Lynne Cheney, although present, seemed to have no mark on the home. The decor was colorless and tasteless (not that they had a bad taste, but that it reflected no taste at all). A white round table at the entrance had a few perfectly arranged stacks of coffee table books on interior decoration: “At Home With Books,” “At Home With Arts,” etc.

The surroundings were bland, but the conversation with Cheney was spellbinding. To a question about whether his invasion of Iraq may have been a mistake in hindsight, the host’s response was resolute: Iraqis were better off to be bombed by American “weapons of mass love” vs. “everyone else’s weapons of mass destruction.”

Cheney was as skeptical of me as I was of his policies. He grumbled something about how “communists do not reform.”

Both a teacher at the liberal New School—and the great granddaughter of Nikita Khrushchev, Prime Minister of the Soviet Union—Cheney saw me as a Cold War foe. And he, in his unapologetic authority, reminded me of my authoritarian homeland.

Having grown up in the 1970s Soviet Union, I knew my dictators by heart. Generations of them standing on top of the Lenin Mausoleum greeting the Red Square propaganda parades. I recognized Cheney as my own long before anyone else.

I saw this in the way he quieted dissent.

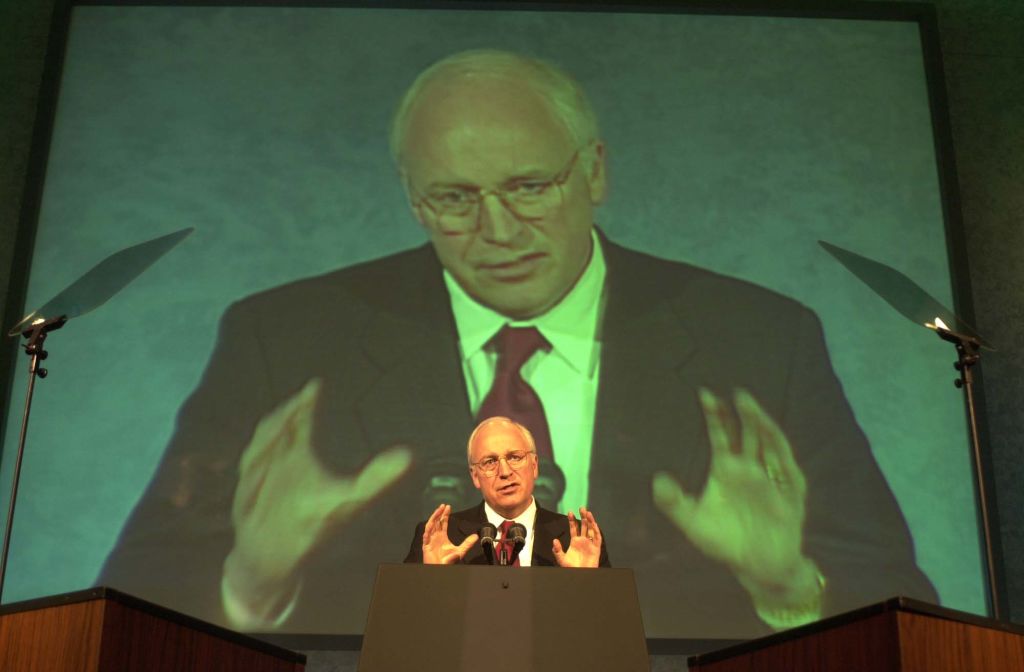

In a 2000 press conference, just after he was nominated as vice president to George W. Bush, Cheney announced that there should be no more questions about the conflict of interests between his future job at the White House and his former job as CEO of Halliburton, an energy company.

The free press was mesmerized by his unapologetic authority. No one dared ask if Cheney had severed contacts with his former business colleagues. (He hadn’t.) No one dared ask if he would receive future payments from the company. (He would.)

As a descendant of Kremlin bosses, Cheney reminded me of the strongmen who manipulated and fear-mongered citizens in the Soviet Union. After the tragic events of 9/11, Bush and Cheney’s global war on terror allowed for several constitutionally questionable U.S. policies: The Patriot Act, The Military Commissions Act, The National Defense Authorization Act. And Americans’ fear of 9/11 permitted the Bush-Cheney White House to approve of torture at secret overseas sites as well as to authorize warrantless surveillance by military agencies—sweeping through the emails and phone calls of millions of Americans.

Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the Soviet Union, once told me that “Cheney was a dangerous man, not what you’d expect in American democracy.”

I was fascinated with Cheney because he could behave in ways that, to critics of the Bush Administration like myself, were reminiscent of authoritarian governments abroad.

So when I finally was able to speak with Cheney that day, I expected him to be powerful and gruff. What I didn’t expect was for him to seemingly still compare himself to Bush’s defense secretary, Donald Rumsfeld.

We traveled to the Rumsfeld estate nearby. It was starkly different—full of life, color and well-worn furniture. Their driveway was covered with cheerful yellow small-pebbled gravel—a sign of true wealth as I later learned—unlike Cheney’s gravel, which was large, grey, and for the Nouveau riche.

It was Rumsfeld, who as a congressman in the 1960s brought the young Cheney to DC, first as his aide, then as his deputy when Rumsfeld became President Gerald Ford’s Chief of Staff. A Princeton graduate, a seasoned Washingtonian, Don was a worthy role model for Dick, the provincial University of Wyoming student. In his later career Cheney, a failed Yalie, inherited Rumsfeld’s leftover positions. He took on the role as Ford’s Chief of Staff when Rumsfeld secured the Secretary of Defense job in 1975. Cheney followed in his footsteps—becoming a congressman in 1978, and a Secretary of Defense in 1989. In 2000, he finally surpassed Rumsfeld by securing the vice presidency. But the Afghanistan and Iraq wars they envisioned together.

Despite the lives lost and billions spent on these wars, the vice-president never reconsidered his views. He never looked back at his Middle East wars and thought, “I wish I’d done something differently.”

As one of Cheney associates explained, “Rather, there was a sense that they hadn’t gone far enough.”