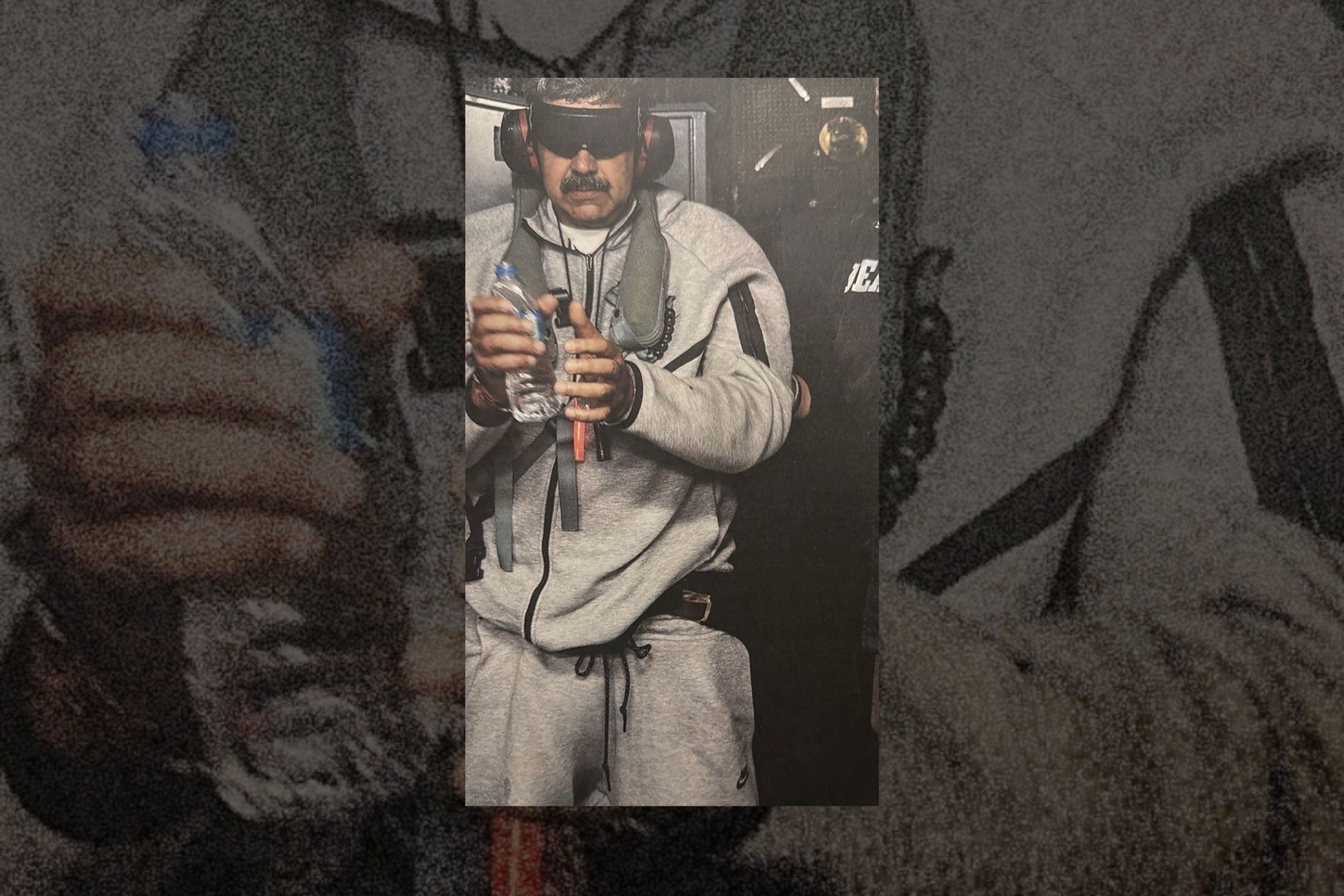

On Jan. 3, hours after the U.S. captured Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro in Caracas, a photograph circulated showing Maduro aboard the USS Iwo Jima wearing a Nike tracksuit. This image moved quickly across global media and was shared, commented on, memed, and folded into the familiar rhythms of contemporary visual culture.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

What drew immediate attention was not only the informality of Maduro’s clothing, but the presence of a globally recognizable brand in a moment typically governed by the visual codes of state power. Athleisure replaced uniform; a logo supplanted insignia. Interpretation was structured less by the language of politics than by that of the marketplace.

The image mattered not because it diminished power, but because it reframed it. A moment of political consequence was filtered through the visual language of branding—familiar, legible, and emotionally neutral—reshaping how the event was absorbed and understood.

In an era when logos often outlast leaders, this reframing feels less anomalous than revealing. The Nike swoosh did not register as a crisis for the brand, nor did it meaningfully erode the gravity of the moment itself. Instead, it redirected attention. A symbol designed for recognition took precedence over institutional markers of authority, subtly reorganizing the viewer’s response.

Power has always relied on visual form to make itself legible. For centuries, authority announced itself through uniforms, architecture, ceremony, and controlled display—systems designed to signal hierarchy, distance, and consequence. Leaders were styled to appear elevated and distinct from ordinary life. Even moments of capture or downfall adhered to this grammar, carefully staged to communicate rupture and finality. Clothing, in this context, functioned as a marker of power.

Contemporary visual culture organizes meaning differently. Today, the most widely circulated symbols are not those of the state, but those of the marketplace. Brands cross borders more freely than political iconography, and arrive with preloaded emotional associations. A recognizable logo requires no explanation; it is instantly understood. Its familiarity feels neutral, even when it quietly shapes interpretation.

What the photographs of Maduro suggest is not the disappearance of power’s visual language, but its entanglement with symbols that operate as cultural shorthand. A useful contrast can be found in the images released after the capture of Saddam Hussein in 2003. Those photographs were engineered to communicate rupture and subjugation: disheveled hair, a visibly diminished body, the unmistakable signs of force. The message was explicit. Power had been stripped away, and the image insisted upon that assessment.

The photographs of Maduro operate differently. The Nike logo carries a distinct and widely shared set of meanings, often associated with athletes, celebrities, and leisure. It functions not as a marker of authority, but as a mechanism of alignment. When placed on a figure historically defined by control and spectacle, it collapses the distance that authoritarian imagery depends upon. Power does not disappear in this image; it is recontextualized.

Aside from the handcuffs, little in the frame signals coercion or loss of control. Dressed in athleisure, Maduro appears composed, almost casual—closer to a figure en route to a tennis match than one forcibly removed from power. Where the image of Hussein communicated consequence through visual degradation, the image of Maduro diffuses consequence through familiarity, structuring interpretation not through rupture, but through normalization.

The response to the photographs of Maduro has not inspired outrage or catharsis; instead, it has generated commentary, irony, and consumption. Searches for “Nike Tech” on Google spiked, and the tracksuit sold out in multiple sizes. The moment was processed less as a reckoning than as a cultural artifact—circulated, annotated, and absorbed into the endless scroll of “content.”

This is not a failure of seriousness so much as a shift in how seriousness is encountered. In a media environment dominated by speed and repetition, images are now interpreted through existing symbolic frameworks before political meaning has time to settle. Brands, by virtue of their ubiquity, have become some of the most powerful of these frameworks.

In this sense, branding now functions as a kind of visual infrastructure. It does not declare authority, but it organizes attention. It offers interpretive cues that feel neutral precisely because they are familiar. Political imagery, once governed by ritual and formality, has become increasingly mediated through symbols designed not for judgment, but for recognition.

This creates a paradox. Brands have been historically understood as apolitical, yet they now carry a disproportionate share of cultural meaning. Their power lies not in persuasion, but in legibility. Governments change. Leaders fall. Logos and brands persist, shaping perception as events move past—or with—them.

The risk here is not that branding overtakes politics, but that it alters how political consequence is felt. When moments of accountability are visually translated into the language of lifestyle, the emotional register shifts. What should feel destabilizing is rendered manageable, familiar, and easily consumed—becoming fodder for late night television rather than collective reckoning.

The image of Nicolás Maduro in Nike athleisure did not trivialize power; it normalized it. And normalization, in this context, may be more corrosive than spectacle. The visual cues did not instruct viewers how to judge the event—they simply made it easier to absorb.

Perhaps the most unsettling aspect of the images of Maduro’s capture is not that power appeared diminished, but that it appeared ordinary. And in a culture where the ordinary is endlessly scrollable, is our scrolling the final transformation of power itself?