Speaker Kevin McCarthy is struggling to pass a bill to fund the government — and the White House isn’t about to throw him a lifeline.

With just days to go before the government runs out of money, Biden’s team is watching Congress steam toward a shutdown, resigned to the reality that there’s little they can do now to fix the situation and confident the politics will play out their way.

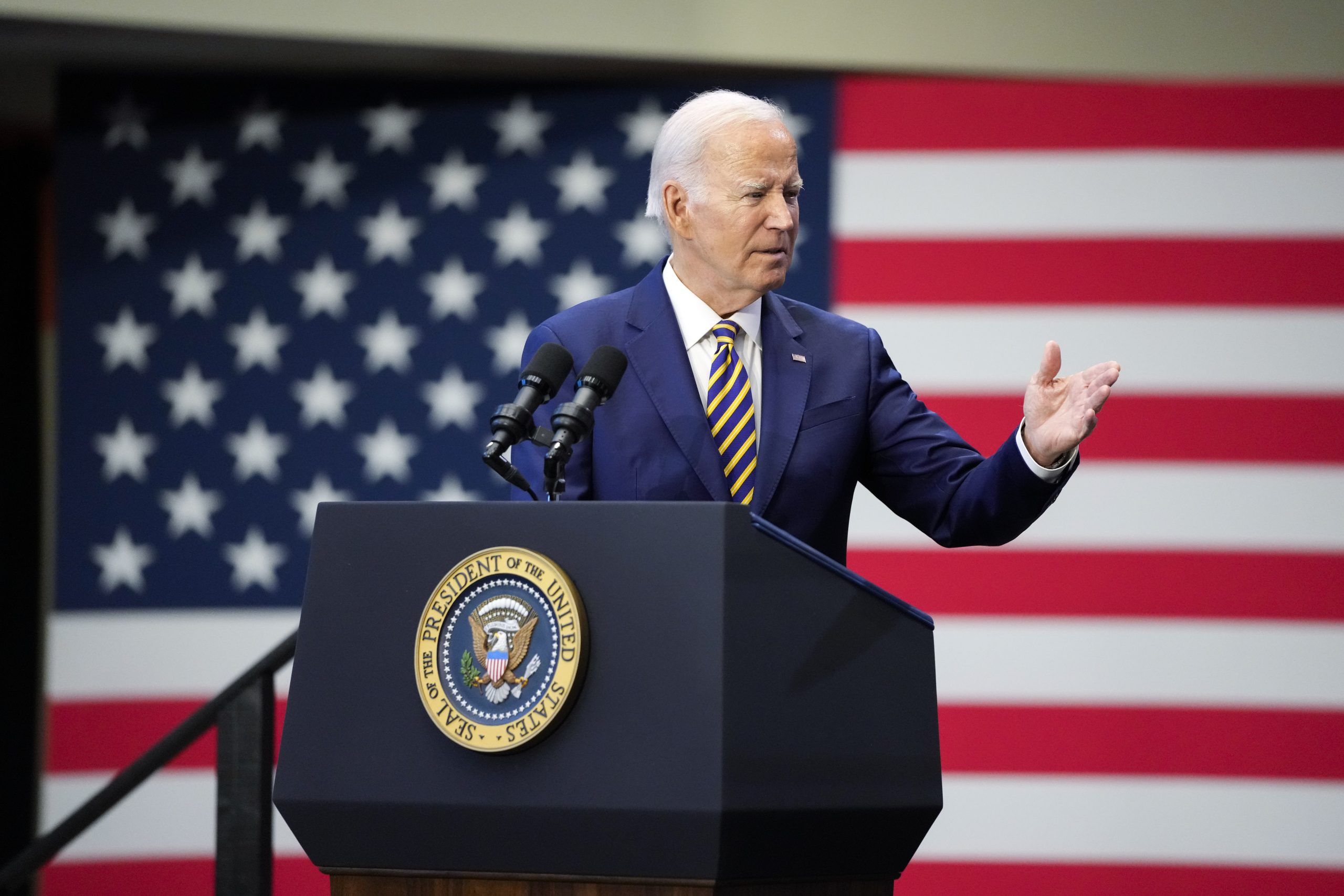

President Joe Biden has steered well clear of the chaos engulfing the House, where Republicans are battling each other over a government funding bill. Within the White House, aides have settled on a hard-line strategy aimed at pressuring McCarthy to stick to a spending deal he struck with Biden back in May rather than attempt to patch together a new bipartisan bill.

“We agreed to the budget deal and a deal is a deal — House GOP should abide by it,” said a White House official granted anonymity to discuss the private calculations. Their “chaos is making the case that they are responsible if there is a shutdown.”

Biden world’s wait-and-see approach comes against the backdrop of an increasingly likely shutdown, which would be the first of the Biden era.

On Tuesday, GOP leadership canceled plans for a procedural vote on a short term funding bill, wary it had the numbers to pass. Hours later, hard-right conservatives tanked a procedural vote related to a defense spending bill. Moderate House Democrats have been working on a last-ditch fall back option to avert a shutdown, but any final product will need approval from the Senate.

For now, the White House is staying out of the mix, trying instead to draw a contrast between the House majority that can’t complete the task of keeping the government’s lights on and Biden, who on Tuesday addressed the United Nations General Assembly in New York. It’s also highlighting the price of the latest GOP plan, such as, in their estimation, cutting 800 Customs and Border Protection agents and 110,000 Head Start positions for children.

The administration has hitched its wagon to a Senate effort widely supported by members of both parties in that chamber. The top Republican and Democratic appropriators are working on long-term, bipartisan funding bills that adhere to the agreed upon spending levels, although they have accepted that a stop-gap funding bill will be needed. There is a sense in the White House and on Capitol Hill that support for the Senate bill would increase if it becomes evident that McCarthy can’t steer his conference.

Getting involved now, White House officials reasoned, would only lend credibility to an attempt by conservative lawmakers to effectively rip up the Biden-McCarthy deal agreed to during debt ceiling talks in the spring and extract deeper cuts from the administration. It also would risk further angering progressives, who already didn’t like the funding levels in that spring agreement.

“The White House is there. The House Democrats are there, and the Senate Democrats and Republicans,” said Rep. Rosa Delauro (D-Conn.), the Democrats’ top appropriator. “It’s just this recalcitrant group of House Republicans.”

The administration is not entirely hands off, though. Senior administration officials, chiefly OMB Director Shalanda Young, have been in touch with lawmakers in both chambers and parties.

It’s not clear how Biden’s involvement would help the effort. House Republicans are sparring among themselves on the shape of a government funding bill. So far, there is no clamoring among them for the White House or Biden to be at the table.

“The drama is always, can Kevin McCarthy pass a bill and keep his job,” said Jim Kessler, vice president for policy at centrist Democratic think tank Third Way. “And Biden can’t solve that problem.”

The hands-off approach is not without risk.

The president may have to step in at the last minute to smooth over a final agreement. Biden has a history of engaging in talks even after first striking a posture that he won’t negotiate, like during the debt ceiling dispute.

Even though some Republicans have openly called for a shutdown, the public could end up holding the White House responsible for the delayed paychecks to federal workers and Social Security recipients and the national park closures that come along with an extended government closure.

“Shutdowns are incredibly damaging,” said Rep. Derek Kilmer (D-Wash.), who described how it took a year for a hotel operator in his district to make back the money it lost when the last government shutdown closed a nearby national park. “I’m less concerned about the politics and more concerned about my constituents.”

Biden’s involvement now would likely only thwart negotiations among congressional leaders, because any proposal that draws a modicum of White House support would prompt immediate opposition from House conservatives.

“You just have to let the House have its temper tantrums, have its fits, prove that it’s incapable of doing anything before you can step in and offer a path out of it,” said Brendan Buck, a former top aide to then-House Speakers Paul Ryan and John Boehner. It may just take a shutdown before McCarthy feels comfortable coming to the table, he added. “He’s going to need to show folks that he’s willing to go full length on this — whatever that may look like in their minds.”

But even as small groups of lawmakers hold tentative bipartisan conversations about a path forward, Rep. Richie Neal (D-Mass.), the top Democrat on the Ways and Means Committee, cast aside any concern about political fallout — for his fellow Democrats, at least.

“The entire federal government expenditure is being held hostage by about 25 Republicans in the House,” he said. “If you talk to Republicans privately here, genuinely and sincerely, they know they cannot win a government shutdown.”

Buoying the White House’s position is the increasing isolation of House Republicans, a sharp contrast from when McCarthy had the support of Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and Senate Republicans during the debt talks. Now, they want to see the House boost defense spending and share little appetite for the House’s ambivalence about walking to the edge of a shutdown.

DeLauro was among the skeptics of the debt ceiling deal the White House cut with McCarthy in May, believing at the time that its spending limits were too stringent. But like it or not, the two sides’ leaders struck a deal both sides had little choice but to follow.

“I did not vote for the budget agreement,” she said. “But now it’s the law of the land, let’s go. We have a template. Let’s go, let’s move.”