Warning: This post contains spoilers for Frankenstein.

“Believe me, Frankenstein, I was benevolent; my soul glowed with love and humanity, but am I not alone, miserably alone? You, my creator, abhor me; what hope can I gather from your fellow creatures, who owe me nothing? They spurn and hate me.”

If you had to sum up the overarching thesis of writer-director Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein film with one line from Mary Shelley’s seminal 1818 novel, the above quote would certainly be a worthy candidate. Considering del Toro has made a career of subverting the idea that monsters are inherently villainous—think previous offerings like Pan’s Labyrinth and Best Picture winner The Shape of Water—and has described the so-called Creature from Shelley’s gothic horror classic as his “patron saint,” it makes sense this would be the thematic thread he would choose to tug on.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

But if you’re a Shelley purist, you may take issue with how infrequently del Toro’s Creature takes actions that could actually be considered monstrous in the first place. While Shelley presents the Creature as a being who is robbed of his innocence by his creator’s neglect and society’s prejudice, she still finds him ultimately responsible for his own vengeful rage and the horrific crimes he commits in response to his rejection.

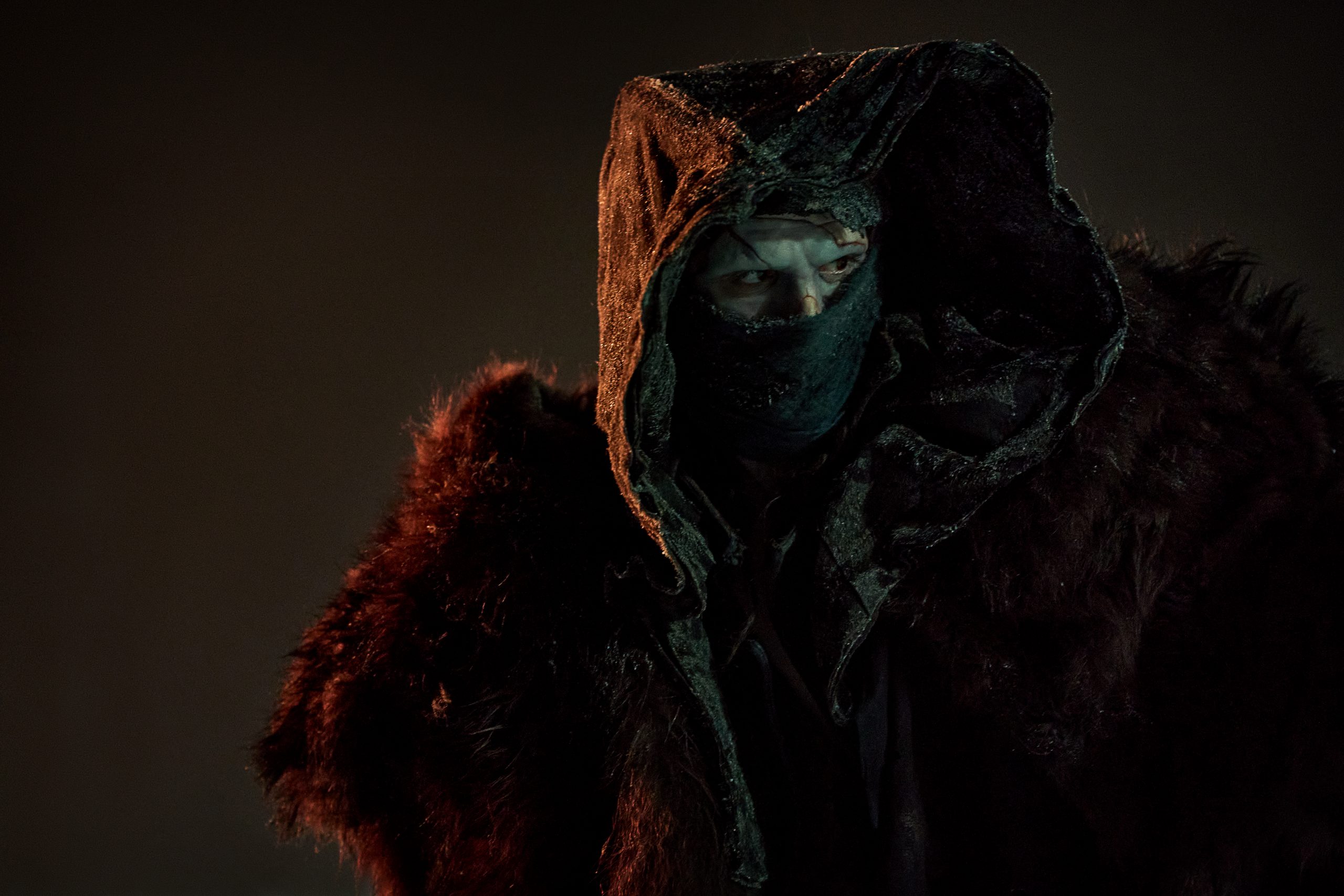

In del Toro’s Frankenstein, in select theaters Oct. 17 and streaming on Netflix Nov. 7, the Creature (played by Jacob Elordi) carries out barely any of the same evil deeds he does in the novel. On the page, these serve to paint him in a monstrous light following his abandonment by his egotistical and cruel creator, Victor Frankenstein (Oscar Isaac). On-screen, this creates a distinctly different result. “I’ve lived with Mary Shelley’s creation all my life,” del Toro told Netflix’s Tudum of his approach to the source material. “For me, it’s the Bible. But I wanted to make it my own, to sing it back in a different key with a different emotion.”

Read More: Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein May Be Grand, But It’s Not Quite Great

How is del Toro’s Creature different from Shelley’s?

In Shelley’s book, the Creature either directly murders or is responsible for the deaths of several innocent people as part as his quest for vengeance against Victor. His victims include Victor’s younger brother William, who is only a child and much younger than the movie’s adult William (played by Felix Kammerer); Justine Moritz, a young woman who is executed after being framed for William’s murder by the Creature; Victor’s best friend Henry; and Victor’s fiancée Elizabeth, who is engaged to William in the movie instead of his brother.

Del Toro, on the other hand, portrays the Creature as a far more empathetic and compassionate figure. When he pays Victor a visit to beg for a companion on what is supposed to be William and Elizabeth’s wedding day, Victor ends up framing the Creature for the murder of Elizabeth (Mia Goth)—one of the few people to ever show him kindness and understanding—after Victor accidentally shoots her himself.

From the moment the Creature is brought to life, his existence is defined by torment and pain. Yet, in the movie, the only person he truly targets in return is Victor. While there are some additional casualties, like the sailors manning the Horizon who try to attack him to defend Victor, his ire never extends to Victor’s family and friends.

What about the ending of del Toro’s Frankenstein?

By the time Victor is chasing the Creature across the Arctic in the final section of the movie, it’s difficult not to be fully on the side of the latter. Still, after creator and creation recount their experiences to each other, the Creature finds it in his heart to forgive Victor. He also comes to the conclusion that since he is incapable of dying—unlike in the book, in which he is able to commit suicide by fire—he must find a way to truly live.

“[The Creature] decides that, regardless of all the hell and the anguish and the suffering…he’s going to live,” Elordi said of his character’s fate at Frankenstein‘s premiere earlier this month. “I carry that with me after making the film, and I’m incredibly grateful to Guillermo for sort of singing that song of hope.”

In the book, Victor and the Creature are both monsters in their own right who push each other to succumb to their worst impulses. They also never get the chance to hear each other’s sides of the story, and Victor dies on the ship in the Arctic wishing he could’ve put an end to his creation. Once the Creature learns about his creator’s demise, he expresses regret for his wrongs and resolves to self-immolate on a pyre in order to rid the world of a body society has shunned—a result of science unrestrained by empathy—and find the only peace available to him.

According to del Toro, the choice to end the movie on a more optimistic note than the novel was borne from his own life. In an interview with the Toronto Star, he described his Frankenstein as the story of the “chain of pain” that fathers pass down to their sons and how challenging it is to break those generational patterns of behavior.

“If I’d made it when I was younger, it would have just been the gripes of a son toward a father,” he said. “Now it’s about the desire for forgiveness of a father who was originally a son, and who realizes life has thrown him into a role he’s not fulfilling…That’s very biographical. That’s not in the book. That’s not Mary Shelley. That’s me.”