Once upon a time, in a cave just north of Durango, Mexico, someone took a poop. In fact, it was quite a few someones, and these events were spread out over quite a bit of time—from about 725 A.D. to 920 A.D., researchers now believe. Thanks to the cave’s arid conditions, when archaeologists excavated the place in the 1950s, the poop was in pretty good shape. Weathered, dry, and packed full of fiber, these stool samples have given scientists a valuable look into what kind of sustenance long-ago people got by on—and what lived in their guts.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

The deposits from the cave are now well-traveled, having made their way to various labs interested in studying them. In 2021, one global team of collaborators analyzed the DNA contained in the old poop—or paleofeces, as it’s delicately known—to see if they could identify the microbes in the poopers’ gut microbiomes.

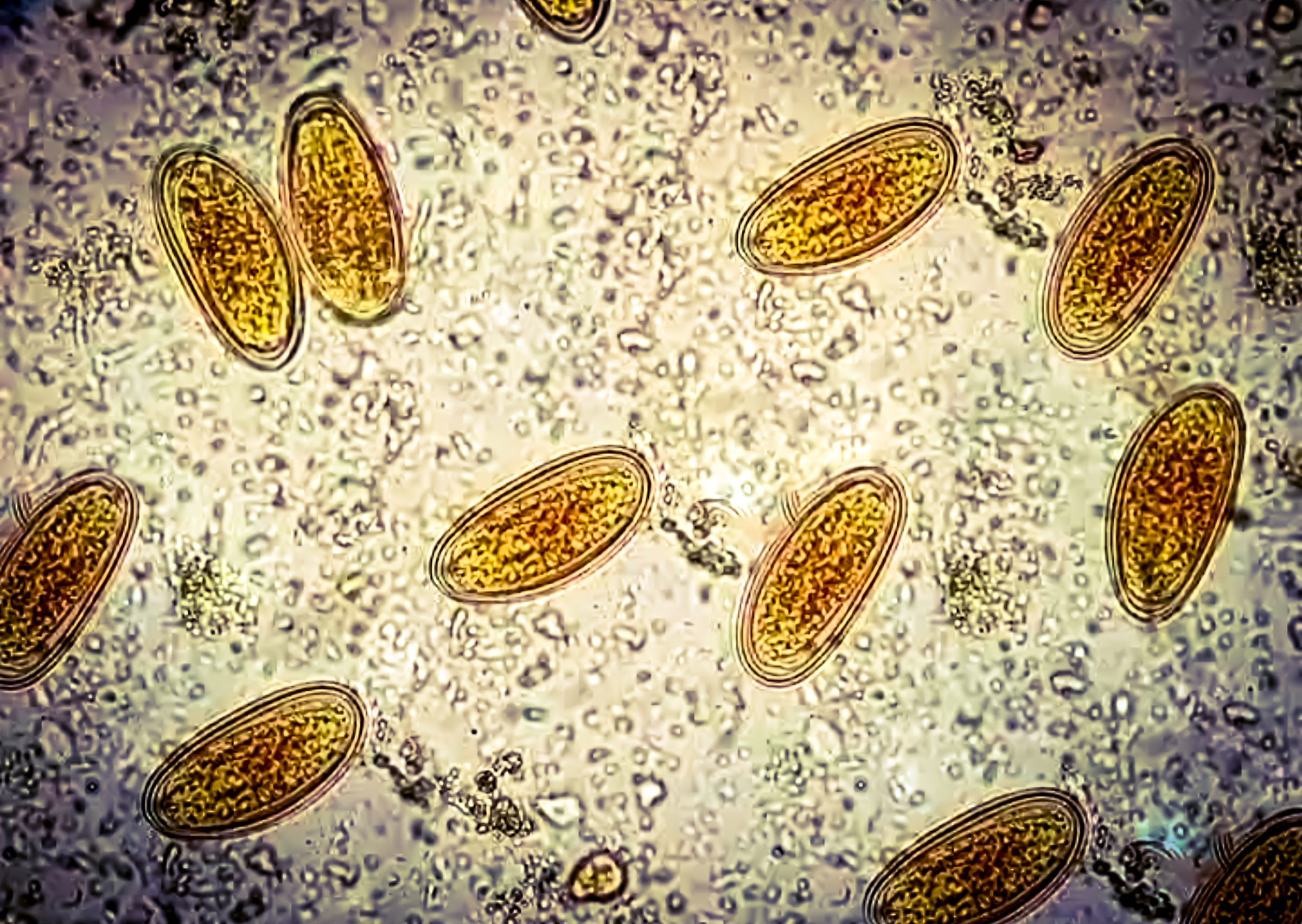

Now, in a new paper published in PLoS One, another group of researchers took a fresh look at DNA taken from 10 of the poops. Their results largely confirm an earlier finding: The people who made these poops were host to a menagerie of parasites.

Playing host to worms

Usually, the poop that Drew Capone, the study’s lead author, works with is much fresher. An environmental microbiologist at Indiana University, Capone studies how sanitation impacts health. “Our work is looking at, ‘How does poop get in the environment? Where is poop in the environment? How does infrastructure stop poop from getting into the environment? And then, what are the pediatric health impacts of poop?’” he says.

Capone and his colleagues were interested in using techniques for detecting pathogens in modern feces on ancient feces. These methods sort through the DNA in a sample looking for specific genes that are signatures of parasites like pinworms, as well as bacterial pathogens.

Read More: You Might Be Hosting a Parasite Right Now. Here’s How to Tell

To extract that DNA, the researchers had to get samples from the paleofeces from the cave. It was harder than they expected: “We had to grind these ancient feces into a powder. We couldn’t really break off pieces,” says Capone. They performed the procedure to look for DNA matches, and got results suggesting a number of different pathogens were in the poop, including pinworms, the protozoan parasite giardia, and various pathogenic bacteria.

Many of the feces came back as positive for multiple organisms. In Capone’s experience, such a large number of pathogens isn’t uncommon in places with poor sanitation, which makes him suspect that the people who deposited these poops so many centuries ago were in a similar situation.

Why choice of technique matters

However, there are reasons why most labs working with ancient DNA don’t use these procedures anymore, say Kirsten Bos and Alexander Hubener, both specialists in ancient DNA at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. DNA tends to fall apart over time, fraying and fragmenting. The older technique used in the PLoS ONE paper favors longer pieces of DNA, which means it’s hard to be sure that what you’re seeing is actually ancient DNA and not modern DNA that’s crept in by accident. Labs that specialize in ancient DNA have high-tech clean rooms to minimize contamination. They also use next-generation sequencing optimized for such a fragile substance.

Additionally, most labs would check the ends of the DNA fragments, where distinctive fraying occurs, to confirm that what they are looking at is truly old. With the technique in the PLoS ONE paper, “you can’t tell easily whether these chemical modifications that occur in ancient DNA have happened,” Bos says.

Read More: 5 Gastroenterologists on the 1 Thing You Should Do Every Day

Capone argues that many of the organisms tested for aren’t able to live long outside the human gut, so the risk of getting a false positive from modern DNA picked up in the poop’s travels might be fairly small. Plus, specialized ancient DNA labwork can be costly, and this older technique is more accessible.

Hubener, who was part of the team behind the 2021 paper analyzing poop samples from the cave, says he’s skeptical of the matches with bacteria—these can be particularly tricky to identify in ancient samples with this technique. However, given what his team found, and given what we know about the biology of parasites, he says the findings on larger parasites like worms are on somewhat firmer footing. “That is, for me, believable,” says Hubener.

What would have been particularly interesting would have been using both the old techniques and the new ones on the same samples, says Bos. That would make it clear what the older techniques can reliably pick up on that also shows up with the newer, most stringent procedures.

“That would have been a really good way to move forward,” she says.