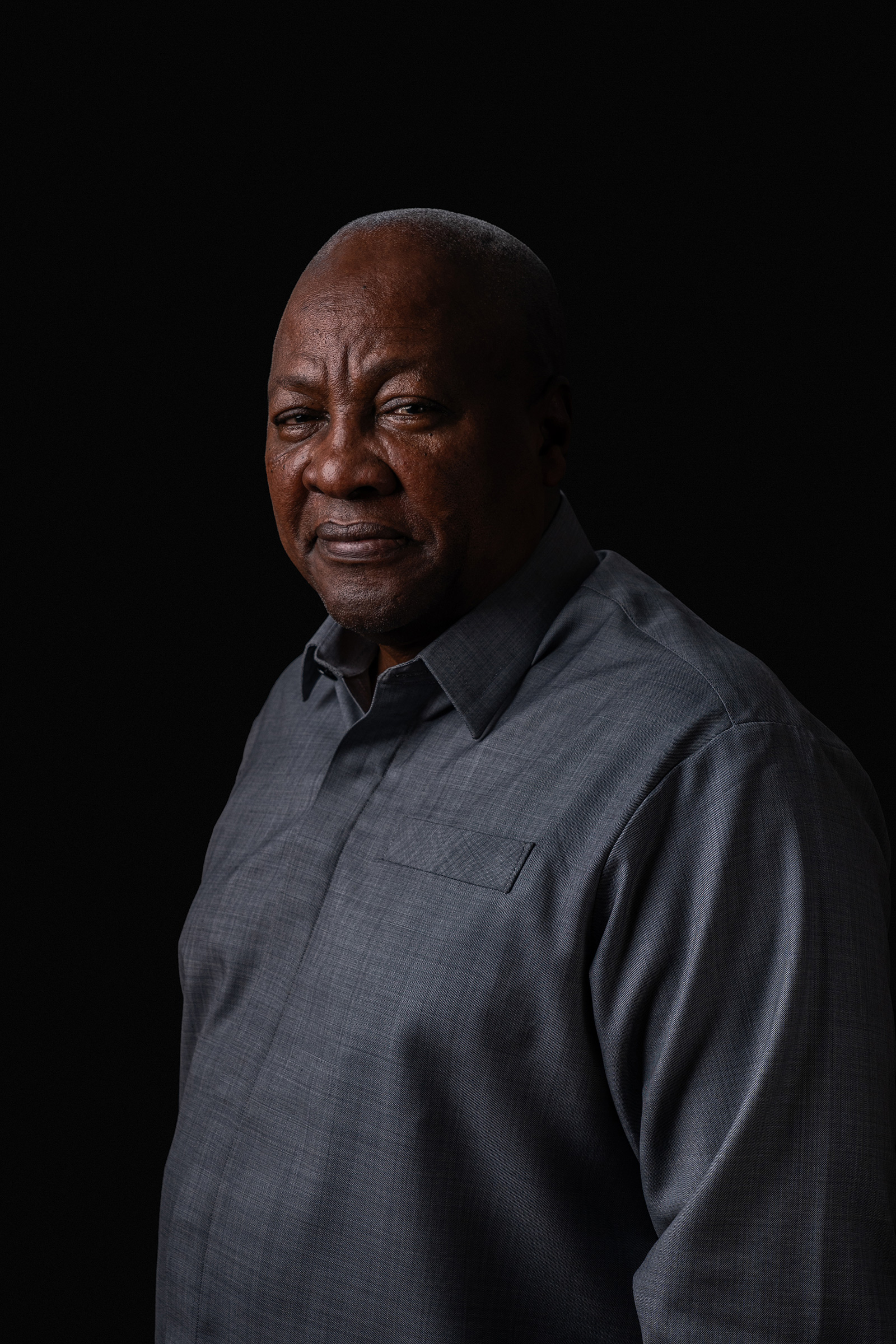

“It will get me into trouble again!” laughs Ghana President John Mahama upon the conclusion of our interview.

A few weeks earlier, Mahama’s Foreign Minister had visited the U.S. State Department, only to be immediately confronted with an op-ed that his boss had written for the U.K. Guardian newspaper. In it, Mahama eruditely excoriates U.S. President Donald Trump’s baseless claims of a white genocide in South Africa and calls his “unfounded attack” on its President Cyril Ramaphosa in a fractious Oval Office meeting “an insult to all Africans.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

“They asked, ‘Did your President actually write this?’” Mahama tells TIME in his presidential office within Accra’s Jubilee House. “He says, ‘Yes, my President is a writer and likes to express himself.’ And they said, ‘Well, he’s President now. Can you ask him to put his pen down?’”

Even if Mahama does acquiesce and pause his writing, it’s extremely doubtful he will ever stop shooting from the hip. On Sept. 25, the 66-year-old used a speech at the U.N. General Assembly to accuse its Security Council of exercising “almost totalitarian guardianship over the rest of the world,” while demanding that an African member be added to this apex body and the abolition of its veto power. “The future is African!” he said to rapturous applause.

A little showy, sure—but far from empty talk. By the year 2050, over 25% of the world’s population is expected to hail from the African continent, including a third of those aged 15 to 24. Africa’s combined GDP was $2.6 trillion in 2020 but is projected to reach $29 trillion by 2050. Africa boasts three of the world’s 20 fastest-growing tech hubs, including first place: Nigeria’s Lagos.

But while the trajectory is indubitable, the ascent is far from smooth, as Ghana’s recent experiences neatly encapsulate. The West African nation of 34 million has long been painted as a continental success story due to its democratic and economic stability. However, Mahama was returned for a second nonconsecutive term in January with his homeland embroiled in an acute economic malaise, characterized by a huge debt burden, soaring costs, and youth unemployment at a staggering 38.8%.

In just half a year, Mahama succeeded in restoring stability—halving inflation, strengthening the national cedi currency by 30%, and embarked on a radical “Resetting Ghana” agenda. He rolled out a 24-hour economy to empower businesses and public institutions to operate around the clock, abolished onerous levies on online purchases and betting wins, and established a code of conduct for all government officials to fight corruption. He pledged to wipe fees for all first-year students in public tertiary institutions and distribute free feminine hygiene products to school-age girls nationwide. To fight joblessness, he unveiled plans to train one million coders over four years, providing the talent to bolster a nascent tech sector.

“We must improve security to make sure that the streets are safe for people to be able to go to work and come back,” says Mahama. “So we know what our responsibilities are.”

But politics is dealing with the unforeseen, and an almighty curveball was looming over the Pacific. Less than three weeks after Mahama’s Jan. 7 inauguration, the Trump Administration began gutting USAID, which had allocated $12.7 billion to sub-Saharan Africa, accounting for 0.6% of the region’s GDP.

According to the Pretoria-based Institute of Security Studies, the aid cuts could push 5.7 million more Africans into extreme poverty by next year. Meanwhile, two to four million additional Africans are likely to die annually as a result of reduced global aid budgets, estimates the Africa Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Within South Africa alone, cuts to HIV/AIDS programs could result in an additional 500,000 deaths over the next decade, reports the Desmond Tutu HIV Center.

Ghana lost $156 million allocated for HIV and AIDS control, combatting malaria, as well as research, governance, and education. Still, the cuts were “not fatal,” says Mahama. “All I did was to tell our Finance Minister to make adjustments … so we have covered it with our budget. We’re fine, but not so in some other countries. I was speaking to one of my colleague presidents and the USAID withdrawal has shut down their school feeding program. With countries like that, it will have quite a huge effect.”

As such, Mahama’s term coincides with a new paradigm for Africa. Despite vast agricultural and mineral wealth, the continent faces limited access to global markets, unfair trading conditions, and a lack of investment. These challenges hinder economic growth, perpetuate poverty, and prevent many Africans from realizing their full potential.

The hope is that, armed with new technology, that decline of foreign aid serves a rallying call that compels African countries to forge their own paths, free from the constraints of aid dependency and external policy pressures. And while challenges persist, there are already signs that hidebound profligacy is being replaced by newfound autarky. “Ghana will manage,” says Mahama. “And it teaches us to be self-reliant.”

Mahama talks with an unruffled, languid poise that belies the candor of his words—a fitting tribune for a new era of African confidence. He was born in the small town of Damongo in Ghana’s bucolic northwest. His father was a prominent rice farmer and local MP under Ghana’s first post-colonial leader, Kwame Nkrumah. After graduating with a degree in history from the University of Ghana, Mahama taught at a secondary school before pursuing a post-graduate degree in social psychology in Moscow, graduating in 1988. His experiences amid the Soviet Union’s death throes burnished the impression that every nation must forge its own path distinct from cookie-cutter dogma. After returning to Ghana, Mahama worked for the Japanese Embassy and Plan International NGO before standing for parliament in 1996.

Mahama’s first term as president from 2012 until 2017 might best be described as underwhelming. There was a severe power crisis and a slew of corruption allegations, including the revelation that Mahama received a Ford Expedition valued at $100,000 from a contractor while serving as vice president. (A subsequent probe cleared Mahama of graft, though decreed the gift broke rules and the car was returned.) GDP dropped from 9.3% when Mahama began his term to a low of 2.1% in 2015.

By 2017, growth had recovered to 8.1% but by then voters had made up their minds not to hand Mahama a second term. Yet his successor fared even worse, plunging Ghana into an economic crisis owing to fiscal mismanagement, a lack of economic diversification, and excessive public debt from unsustainable borrowing and spending. In 2022, Ghana—the world’s sixth-biggest producer of gold and number two exporter of cocoa—defaulted on its domestic and foreign debt obligations.

It hasn’t taken long for Mahama to steady the ship—success rendered all the more impressive against the background of aid cuts. Problems with the aid culture are well-documented. While aid provided ready cash, only a tiny fraction actually went to African stakeholders themselves. USAID tried stridently to have a quarter of their budget spent through local organizations. However, the highest they ever achieved was about 10%, and last year, it actually dropped. “Western consulting companies, contractors, think tanks, NGOs, got a lot of the money that was meant to go to Africa,” says Bright Simons, head of research at the IMANI Centre for Policy and Education, an Accra-based think-tank. “So Africans were never able to build capacity with this money.”

In healthy economies, citizens pay income taxes in return for public goods. Repeated studies have shown how foreign aid short-circuits this relationship, making governments accountable to donors rather than constituents, who spared the hardship of paying levies are less likely to hold officials to account. Meanwhile, the easy access to cash gnaws away at professionalism and fosters corruption. Every year, an estimated $88.6 billion—some 3.7% of Africa’s GDP—leaves the continent as illicit capital flight, according to U.N. data.

“Aid engenders laziness on the part of the African policymakers,” writes Baroness Dambisa Moyo, a Zambia-born economist in Dead Aid: Why aid is not working and how there is another way for Africa. “This may in part explain why, among many African leaders, there prevails a kind of insouciance, a lack of urgency, in remedying Africa’s critical woes.”

It’s criticism that has become widely accepted. Zambia’s President Hakainde Hichilema described the USAID cuts as a “long overdue” wake-up call, while his Rwandan counterpart, Paul Kagame, opined that the continent cannot “rely on the generosity of others forever,” adding: “I think from being hurt, we might learn some lessons.” While Mahama laments the way the aid Band-Aid was ripped off, he says that the end result will be positive—even if there are harsh lessons for Africa regarding U.S. priorities in this new world order. Aside from the aid withdrawal, the Trump Administration has hiked tariffs across Africa, including 15% on Ghanaian exports. Mahama cannot hide his frustration.

“One country cannot say, ‘I want to be an island by myself, so I’ll slap tariffs on you because I want to bring manufacturing back,’” says Mahama. “These tariff negotiations took many years under the WTO to achieve, and so for one person to start slapping everybody with tariffs.” Mahama breaks off in exasperation. “I don’t think it’s a very effective way of conducting foreign policy.”

What the aid cuts and tariff hikes mean for America’s standing overseas remains to be seen. After all, USAID was founded by President John F. Kennedy by executive order in 1961 at the height of the Cold War precisely to counter overseas Soviet influence. Today, the U.S. is embroiled in a new era of Great Power competition with China, whose clout is swelling across the globe, not least in resource-rich Africa. Mahama says the Trump administration’s nativist pivot “takes away U.S. soft power and opens [Africa] up for other players to come in.”

It’s not just superpowers that are clamoring for a piece of the action. Gulf nations, India, and Europe are seeking to leverage the opportunity. In August, London Mayor Sadiq Khan made the first ever African trade mission by a holder of his office, visiting Ghana as well as Nigeria and South Africa. “At a time when President Trump is attacking international students, we in the U.K. should be encouraging talented international students to come to our British universities,” he told TIME in Accra.

Still, the U.S. denies that it is in retreat, with the State Department highlighting the more than 100 American companies doing business in Ghana across many sectors, including oil and gas, healthcare, small modular nuclear reactors, and mining. On July 24, Google launched its Artificial Intelligence Community Center in Accra alongside $37 million in support for research and innovation in Africa. In particular, Rolf Olson, Chargé d’Affaires ad interim at the U.S. Embassy in Accra, insists to TIME that Washington is “ready to partner with President Mahama and his administration in combating illegal and corrupt activity” such as illegal gold mining, which he says “has been fed by foreign actors, including Chinese firms and nationals.”

Yet the adversarial tone isn’t shared by Mahama, who says “the Chinese government has been supportive” of law enforcement efforts. “I don’t like to focus on just China.” And the fact that Washington is quite clearly preoccupied with Beijing renders the new U.S. posture “surprising,” says Mahama. “I can understand U.S. insecurity when it comes to China … but that’s when you need your allies. That’s when you need Canada, that’s when you need Mexico, that’s when you need the E.U. But if you are threatening the E.U. and all others with 50% tariff increases, South American countries with 100% tariff increases, you can’t tell the objective of this whole policy. Collaboration would have been better than the current global tensions.”

Washington’s efforts to paint China as the bad guy are undermined by the clear perception that American engagement is now rooted in interests rather than values. Still, while China has been ramping up its overseas investment, especially through its $1 trillion Belt and Road Initiative—a trade and infrastructure network spanning the globe—there’s little chance it will (or even wants to) replace U.S. wholesale.

While Beijing is laser focused on ports, pipelines, and railways, the type of capacity-building engagement long characterized by USAID isn’t part of their strategy. China won’t fund projects promoting gender equity, affirmative action, training impartial judges, or improvements on regulatory performance in African nations as these are not things that its government values at home.

Although self-reliance is Africa’s goal, the challenge is achieving true autonomy without structural transformation of nations that remain highly unproductive. Every country around the planet that has achieved structural transformation—from the Asian Tigers to the Balkans—has relied on large injections of foreign capital. Because when the status quo in sub-Saharan Africa is so unsatisfactory—with substandard education, healthcare, security, and so on—these tend to be the focus of domestic resources. Consequently, the bulk of future-focused projects are funded by donor agencies: green transition, incorporating AI, youth leadership, media literacy.

In Ghana, for instance, USAID was a big investor in eco-tourism—attracting foreign visitors to nature sites to provide alternative livelihoods, so people will move away from illegal mining. “So even though the overall amount of aid is small, when you remove it you create a very big gap in that future-rented segment of the country’s structural transformation,” says Simons of IMANI. “The future does not often appear as essential because we are so focused on the present. But the present cannot take us anywhere.”

The issue is how to inject capital without falling prey to some of the pitfalls of aid dependency. With commodity prices at record highs, Africa’s natural resource endowments are among the first areas to receive attention. And freed from the client-benefactor relationship that aid engenders, African nations are insisting upon local processing and refining to retain more of the downstream benefits.

“One thing we’d better get away from is this paternalistic attitude,” Khan says. “The ‘helping hand’ is a better approach, because people are then able to trade.”

For decades, the largesse of Western nations put their African counterparts in an awkward predicament, where they must “play polite” while the sovereignty of their resources is diluted, says Marcus Courage, CEO of Africa Practice, a business consultancy. “Now, African governments have recognized that they have more autonomy and must use it to become more self-reliant and to achieve genuine financial sovereignty.”

Guinea, the world’s top bauxite exporter, has begun mandating that foreign mining companies invest in local alumina refineries to increase value. Non-compliant firms, such as Emirates Global Aluminium, have seen licenses withdrawn. In Ghana, the nation’s first commercial gold refinery opened in August 2024 and Mahama launched a new regulator, GoldBod, to crack down on smuggling and boost state revenues. Gold exports have increased 75% year-on-year as a result. “It means that Ghana is able to get more from its gold resources,” says Mahama.

Technology can also help Africa unleash its hidden potential. The continent is home to 60% of the planet’s uncultivated arable land that is capable of sequestering immense amounts of carbon—yet only 16% of the global carbon credits market. This presents an untapped opportunity for African nations to monetize their mature forests and pristine wetlands, which are particularly prized for carbon capture. Opportunities also abound to sell credits for switching from fossil fuel stoves—some 80% of sub-Saharan Africans use wood or charcoal for cooking—to solar or biomass.

So far, Kenya, Gabon, and Tanzania have been first movers with nations like Ghana, Uganda, and Zambia trying to catch up. The Congo Basin rainforest, for one, removes carbon from the atmosphere with a value of $55 billion per year, according to the Center for Global Development (CGD), or equivalent to 36% of the GDP of the six countries that host the forest. “This asset can and should be seen as akin to mineral or oil deposits that have significant benefits for the countries that host them,” argues the CGD in a 2022 report.

Ghana has 288 forest reserves of which 44 have been invaded by illegal gold miners. “We’ve been able to liberate nine of them,” says Mahama. “And we have a program for starting a reclamation of those forest reserves to restore them.”

But it’s not just carbon. While the world gushes over Africa’s natural resources, trouble brews with utilizing them—pollution, corruption, human rights abuses, criminal infiltration. But what if there was a way to leverage such resources while they remained undisturbed? The global tokenization of illiquid assets—everything from vintage paintings or vinyl records to collectors’ cards or real estate—is slated to become a $16 trillion business opportunity by 2030, according to the Boston Consulting Group. There is a growing clamor to use blockchain technology to tokenize commodities such as Ghana’s gold reserves, Botswana’s diamond reserves, and Zimbabwe’s platinum.

But while more efficient monetization of natural resources would provide a shot in the arm, the crux is leveraging that windfall to diversify the economy beyond extractive industries—futureproofing economies for when commodity prices drop.

Mahama wants Ghana to move past mining and agriculture into processing and agribusiness, including foods and beverages, refined vegetable cooking oils and things like that. “We’re looking at digital services, fintechs, textiles, manufacturing,” he says.

For Mahama, Africa should not just seek to export to developed states but instead trade with itself. He cites the 2018 creation of the African Continental Free Trade Area—the world’s largest free-trade area, comprising a $3 trillion market—as an underutilized opportunity. In July, Narendra Modi came to Accra in the first visit by an Indian Prime Minister for three decades and Mahama says the two leaders discussed sharing technology to boost Ghana’s budding pharmaceutical sector. “Already, we export [pharmaceuticals] in limited ways to our West African neighbors,” says Mahama. “But the African Continental Free Trade Area expands us beyond our 34 million population market to a 1.3 billion market.”

Of course, all this potential requires investment to realize. And while the drying up of no-strings aid money may well prove beneficial in the long-term, the lack of alternative finance remains a problem. While self-financing is the ultimate goal, it will be a long road. African nations collectively possess only 20 sovereign wealth funds with a capitalization of $97.3 billion—less than 1% of the global total.

Compounding issues, many African countries pay four times more interest on their debt than high-income nations despite often having lower debt-to-GDP ratios. As a result, an average African government spends 18% of all state revenue on interest alone, according to the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change (TBI), compared to 3% for E.U. nations.

The TBI has proposed a new cost-efficient $100 billion debt-swap facility administered by multilateral development banks to essentially consolidate and refinance existing liabilities at concessional rates. Kenya, for one, is servicing an international loan of $1.5 billion at 9.5% interest. Refinancing at 3% would save $97.5 million annually.

Of course, $97.5 million is a colossal amount that could be used to fund schools, hospitals, and key infrastructure. Still, it is less than half the $225 million Kenya was due to receive from USAID, of which half in turn was due to be spent on healthcare. The U.S. is not the only country to slash aid—the U.K. is cutting its aid spending from 0.7% of GDP pre-pandemic to 0.3% by 2027—though the manner that USAID was atomized combined with steep tariffs still leaves a nasty taste for Mahama.

“Since the end of the Second World War, we’ve had a world that has been more interdependent and has dealt with international relations in a multilateral fashion,” he says. “Things are changing now. It looks like unilateralism has become the order. But it does not help anybody because the world progresses together.”