The battle over birthright citizenship rages on. On Sept. 26, the Trump Administration filed for expedited review of its executive order restricting the legal scope of the practice. The administration wants the Supreme Court to decide what the Fourteenth Amendment actually mandates, hoping to redefine what it means to be an American citizen.

The administration views ancestry, not a commitment to the nation’s creed, as the foundation of citizenship. Vice President J.D. Vance laid out this vision in a July speech at the Claremont Institute. According to Vance, someone is a rightful American citizen because their grandparents built the country, not because they subscribe to American values — a standard that excludes immigrants.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

While a legal defense about the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment and the original intentions of its authors could win over the Supreme Court, it is important to recognize that the Trump Administration is making a political case to the American people about who really counts as a citizen. In order to win in the court of public opinion, defenders of birthright citizenship must respond in kind and make the case to the American people for why its inclusive ideal is right and just.

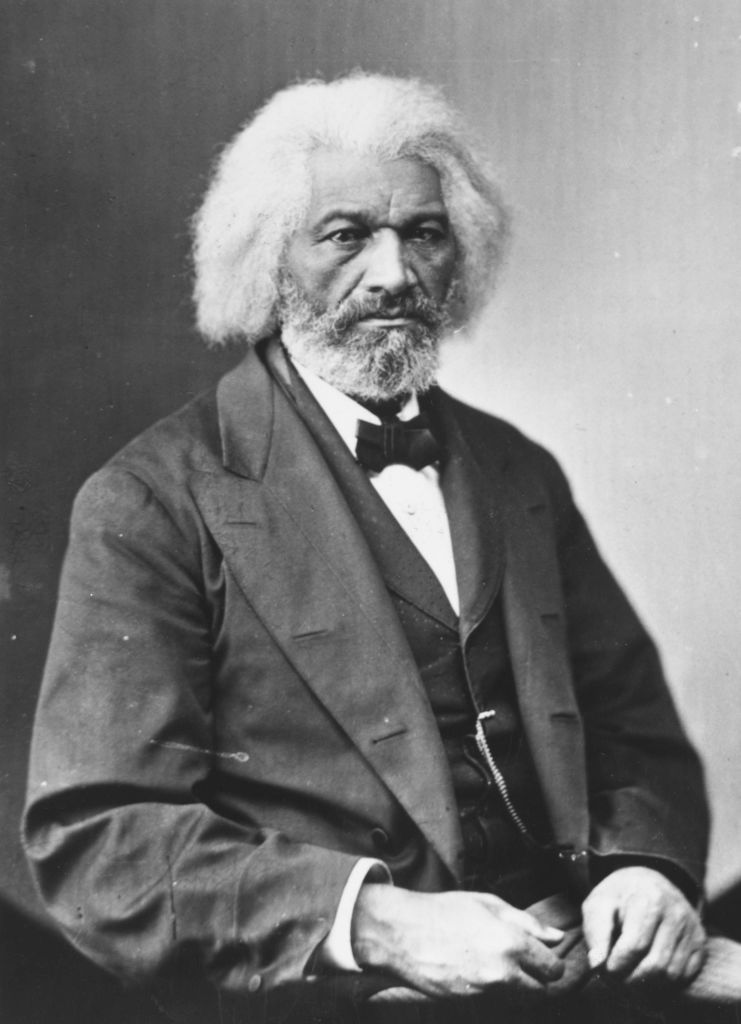

No one offers a better example of how to make that case than Frederick Douglass, the fugitive slave, abolitionist, and eventual statesman involved in the codification of birthright citizenship in 1868. Douglass did share one principle with Vance: He, too, saw one’s contributions to the community as integral to citizenship. Yet, there was a pivotal distinction between the two men’s visions. Douglass waged a fierce campaign in the 1850s and 1860s to broaden the nation’s understanding of just who got credited for having built the country.

Douglass’ vision of American citizenship was rooted in his childhood. The future statesman was born into slavery in 1818 in eastern Maryland. Douglass’ early childhood was defined by separation: from birth, his mother was enslaved on a plantation many miles from where he was raised by his grandmother. When his owner deemed Douglass old enough for plantation labor, his grandmother was also forced to abandon him.

Yet, despite this separation, Douglass became deeply impressed by his mother’s courage and commitment to care for him. One night, as he headed to bed hungry after the plantation cook denied him dinner, Douglass’ mother stole away from the plantation on which she was enslaved to see her son. She upbraided the cook and fixed a meal for him. In his second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, Douglass described this experience as “instructive,” for “that night I learned that I was not only a child, but somebody’s child.”

Read More: History Shows Why Birthright Citizenship is so Important

Chattel slavery, Douglass observed, was designed to destroy the familial bonds of the enslaved. As an adult, his mother’s courageous efforts to preserve their connection came to signify for Douglass how social care had civic value: what made people members of a community was what they did to build up those around them.

Douglass drew upon this connection between labor—broadly conceived—and community when, in the 1850s, he began to argue that Black Americans, whether enslaved or nominally free, were already American citizens. In 1851, he delivered a speech, “The Free Negro’s Place is in America,” which grounded Black Americans’ citizenship in their contributions to the nation: “We levelled your forests, our hands removed the stumps from your fields, and raised the first crops and brought the first produce to your tables…. We have fought for this country…. We are American citizens.” For Douglass, the civic value of Black Americans’ labor was rooted in the fact that it had built up the nation.

In an 1853 speech to the Colored National Convention in Rochester, N.Y., he stressed that this contribution meant that “[b]y birth, we are American citizens; by the principles of the Declaration of Independence, we are American citizens; by the meaning of the United States Constitution, we are American citizens.” In appealing to the nation’s founding documents, Douglass made more than a legal claim about what the text entailed. After all, his view of Black Americans’ standing as U.S. citizens was unshaken by the Supreme Court’s infamous 1857 decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, which denied the legal protections of citizenship to anyone of African descent.

Instead, Douglass made a political claim about who the people as a nation ought to esteem as their civic fellows. Black Americans were citizens, Douglass held, because their labor had been—and continued to be—essential to the American project.

But in twist, Douglass wasn’t simply referring to Black Americans’ physical labor, as he had discussed in his 1851 speech. Instead, he defined their contributions far more broadly. The struggle of Black Americans against slavery, which Douglass understood as quest to force the U.S. to live up to its founding principles, epitomized the kind of labor that formed the foundation of citizenship.

In Douglass’ view, the everyday forms of resistance by enslaved people entitled them to citizenship, as did petitions from free Black Americans to secure their rights and his own efforts as an abolitionist to reshape America’s understanding of what its fundamental values demanded.

Crucially, these efforts involved a push to change the country, not just reproduce the nation as it existed. Black Americans fought to preserve the emancipatory promise Douglass found encoded in the nation’s founding documents, just as his mother had fought to preserve their family in spite of the slave system’s attempts to destroy it.

As Douglass insisted in his most famous speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”, delivered on July 5, 1852, the Declaration of Independence was “ringbolt to the chain of [the] nation’s destiny.” It was the duty of citizens, Douglass argued, “to form an opinion of the constitution, and to propagate that opinion, and to use all honorable means to make his opinion the prevailing one.” Black Americans had made themselves citizens, Douglass claimed, and were entitled to legal recognition as such, because their labor had made the nation what it was. Their struggle to force the country to live up to its founding ideals was also crucial to preserving the promise of what it could be in the future.

Antebellum Black abolitionists like Douglass were the nation’s earliest forceful advocates for birthright citizenship. Douglass believed that birthright citizenship was an essential part of the nation’s civic ethos. But birthright, for Douglass, was a means to legally secure a moral status that Black Americans had seized for themselves through the struggle for their own freedom. That struggle made them builders of the nation.

The underlying political philosophy of Douglass’ arguments for Black citizenship was the idea that all inhabitants of the nation—all who, in the words of the Fourteenth Amendment, “find themselves subject to the jurisdiction thereof”—had a rightful claim to citizenship because all inhabitants contributed to the nation’s potential. They built the nation when they voted, when they worked, and when they cared for their neighbors. In all of these actions, they were participating in the collective project through which Americans as a country continually redefined who they were and what they valued.

After the Civil War, Douglass wielded this conception of citizenship to rail against anti-immigration sentiment directed toward Chinese migrants. In a speech he delivered many times in the late 1860s and early 1870s, “Our Composite Nationality,” Douglass declared: “Since the downfall of slavery and the enfranchisement of the colored race, we have recognized the composite character of the nation, and considered it a blessing rather than a misfortune.” The immigrant, Douglass urged, had a rightful claim to citizenship because her presence shaped who Americans were as a people.

This connection between presence, contribution, and citizenship was the same one that Douglass had wielded before the Civil War to justify birthright citizenship, as well as the citizenship of Black Americans. It was the core of Douglass’s inclusive vision of America.

The debate over birthright citizenship today is not only a moment in which we must defend a legal understanding that has governed this nation for 156 years, but also an opportunity to resurrect Douglass’s vision of an inclusive citizenship. It is one that includes all of our neighbors in the American project. To do so with creativity and clarity is, Douglass reminds us, to fulfill our own responsibilities as citizens.

Philip Yaure is assistant professor of philosophy at Virginia Tech, and a 2025-26 Fellow at the Library of Congress’ John W. Kluge Center. His book, Seizing Citizenship: Frederick Douglass’s Abolitionist Republicanism, was published in July 2025 by Oxford University Press.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.