In a recent Truth Social post, President Donald Trump accused other countries of stealing the “movie making business” from the U.S., announcing a 100% tariff on “any and all movies that are made outside of the US.” Upon first glance, the announcement may seem to be just another iteration of Trump’s widespread efforts to force a return of production to the U.S. via tariffs. But that’s not the full story here. Trump has also indicated that attempts to lure film production away from the country constitute a “National Security threat” and a “concerted effort by other nations” to reach U.S. audiences via the screen, with films that serve as vehicles for “messaging and propaganda.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

This would not be the first time that the U.S. government has directly intervened in both film production and distribution. Like today, past efforts frequently invoked the need to protect U.S. industry and safeguard national security. Yet, they also served as an indirect means to limit the circulation of subversive ideas that political leaders saw as a threat to the status quo. The last time such an effort occurred, the result was decades of far-reaching—if initially voluntary—self-censorship; the specter of government interference set Hollywood on a slippery slope between conformity and authoritarianism.

Government censorship and concern about subversive influence in the film industry go back to its earliest days. In the 1920s, as a Red Scare swept across the U.S. and abroad, fears grew that cinema could negatively affect public order. In particular people worried about films that gestured at alternate political ideologies (socialism in particular) or subjects to do with sexuality, race relations, or morality more broadly conceived.

To assuage these fears, film producers formed the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America and appointed Republican National Committee Chairman Will Hays to lead it. The industry banked on Hays’ conservative credentials to appease those calling for direct government censorship. In 1927, Hays and his team issued a comprehensive set of guidelines, discouraging producers from depicting subjects such as “sexual perversion” and “miscegenation.” These rules were rooted in the belief that “correct entertainment raises the whole standard of a nation” and that no other form of art was as intimately tied to instilling the “moral ideals” and “dividends of democracy” at home and abroad as film.

Read More: The Chaotic, Fantastical World of Donald Trump’s Tariffs

In 1934, this voluntary directive got fangs with the establishment of the Production Code Administration (PCA), a bureaucratic machine created to enforce what became known as the Motion Picture Production Code. Hollywood had decided to self-censor; all major studios agreed not to produce any scripts without a certificate of approval granted by the PCA. Studios complied out of fear that otherwise they faced a slippery slope of increasingly far-reaching government interference.

The code was far from politically neutral, however. It promoted Christian conservative family values and upheld the authority of the dominant political establishment. One of the working principles of the code, for example, was an outright ban on any narrative that “depicted the courts of the land as unjust” or “ministers of religion” as either comical or villainous.

Often, domestic and international agendas converged. When Metro-Goldwyn-Maier sought to adapt Sinclair Lewis’ 1935 novel It Can’t Happen Here, about a fascist takeover of the U.S., for the screen, the PCA declined to greenlight it due to the many “dangerous materials” within the script. In particular, the PCA deemed the depiction of an American totalitarian future to be undesirable and also worried about diplomatic backlash and boycotts of the film abroad due to the rise of fascism in Germany and beyond.

It Can’t Happen Here proved to be just the tip of the iceberg.

The government and the film industry worked in close conjunction to formulate a political agenda that conflated (white) Christian conservative values with American patriotism, in part due to Protestant calls to “clean up the pictures.” The result, however, ironically led to decidedly illiberal strictures and decisions. Joseph Breen, the PCA’s director from 1934-54, a known antisemite, compiled a team of Catholic and Jesuit administrators to put pressure on Hollywood’s Jewish executives. Under the guise of the code’s principle to be “fair” in depicting foreign citizens and political institutions, he blocked a number of anti-fascist and anti-Nazi films from release.

Moreover, in an example of catering to domestic political pressures, the PCA incorporated the values espoused by the powerful white supremacist southern political lobby into its code. It maintained a ban on miscegenation—defined restrictively as “a sex relationship between the white and black races”—in films until 1956.

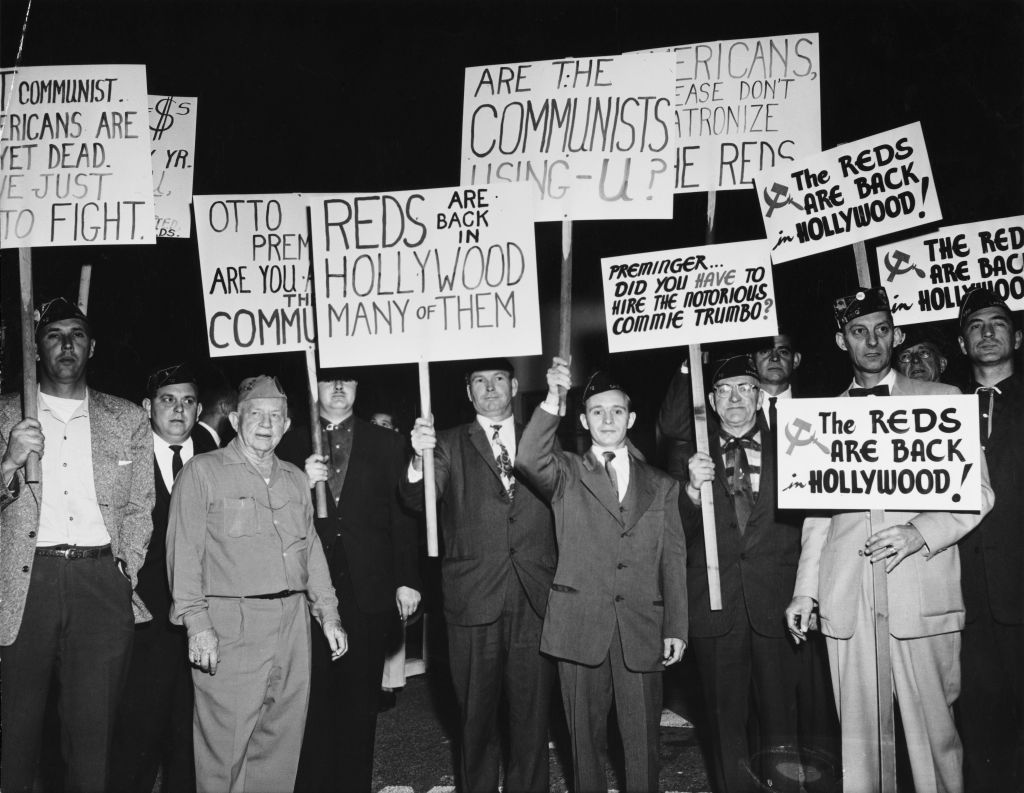

The Cold War only increased the political pressure on Hollywood and further expanded self-censorship practices. Most infamously, the House Un-American Activities inquiry into communist subversion in the motion picture industry resulted in the blacklisting of the “Hollywood Ten” (another self-censorship decision by the industry). In the now-infamous 1947 Waldorf Statement, Eric Johnston, the Head of the Motion Picture Association of America, announced on behalf of all major Hollywood studios that they would terminate the employment of all “subversive and disloyal elements” in the industry, including but not limited to communists. Moreover, the studios sought to broaden their cleanse of the entertainment industry by collaborating with other industry guilds to “eliminate subversive elements” who might be disloyal to the U.S. government or Congress at all levels. The problem was, of course, that subversion was an amorphous label that could be wielded flexibly, which left industry employees scared of weighing in on any topic that could be seen as remotely controversial.

Some U.S. filmmakers and executives rejected these pressures. In an effort to circumvent these strictures and to avoid being bound by the repression and racism they observed in the U.S., they took their entire productions overseas. Imported films were not subject to script approval measures, though they often faced difficulties finding distribution in the U.S. Actress Dorothy Dandridge, who in 1955 became the first ever Black American actress nominated as Best Leading Actress at the Academy Awards, for example, starred in a number of films produced in Italy and France that featured entirely American crews. Making these films in Europe was the only way to offer alternate representations without fear of government intervention.

Read More: Tariffs Don’t Have to Make Economic Sense to Appeal to Trump Voters

Few, however, were willing or able to go this far. At a 1953 Senate hearing about the impact of the U.S. film industry on visions of U.S. democracy at home and abroad, Johnston noted that while he had little information about companies outside of the MPPA, within the major studios, films produced overseas represented only a small fraction of the total output, just “9 or 10 out of some total 352.” Nevertheless, Republican Senator Alexander Wiley of Wisconsin remained concerned about how films produced overseas or by companies not beholden to the Production Code might offer negative representations of the U.S. and its government.

This history mirrors what is happening today.

Today, an administration is once again setting out to promote values and ideologies it sees as American and compatible with its own agenda — albeit embedding this objective in concerns about tariffs, not national security. And as in the past, the threats have created a culture of fear that prompts self-censorship; a recent feature noted that writers and producers are already “self-censoring” out of fear of legal retaliation by the government, license revocations, and loss of advertisers. Earlier this year, actor Sebastian Stan, who received an Academy Award nomination for his role as a young Trump in the 2024 film The Apprentice, was unable to find a partner for Variety’s Actors on Actors series. Stan said actors were “too afraid” after Trump called the film “a politically disgusting hatchet job” and threatened legal action.

The past shows us that more blatant self-censorship—along the lines of the PCA and maybe even the “Hollywood Ten”—could be next.

Tariffs, thus, must be understood as part of this broader project to limit (even the potential for) any form of expression that diverges from the political agenda of the current establishment or is seen as critical of it. The financial consequence may be higher prices for consumers and retaliatory measures by foreign countries on U.S. films. But, most importantly, there will be an inevitable shift in the kinds of stories that will be told if shooting on location becomes confined to the U.S., either to avoid the levy, or out of fear of antagonizing the current administration.

Suzanne Enzerink is assistant professor of American Studies at the University of Sankt Gallen, Switzerland. Her first monograph recovers transnational cultural circuits and subversive visions of race and sexuality in the early Cold War period. She is now commencing a second project which investigates the transnational architecture of far-right cultural imaginaries throughout the 20th-century.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.