Two contrasting adjectives define the American role in the Middle East today: America, the unreliable, and America, the indispensable. Discontent with American foreign policy remains high from Amman to Ankara, from Cairo to Doha, from Baghdad to Riyadh, but the rulers of the region have been vigorously courting the Trump Administration.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

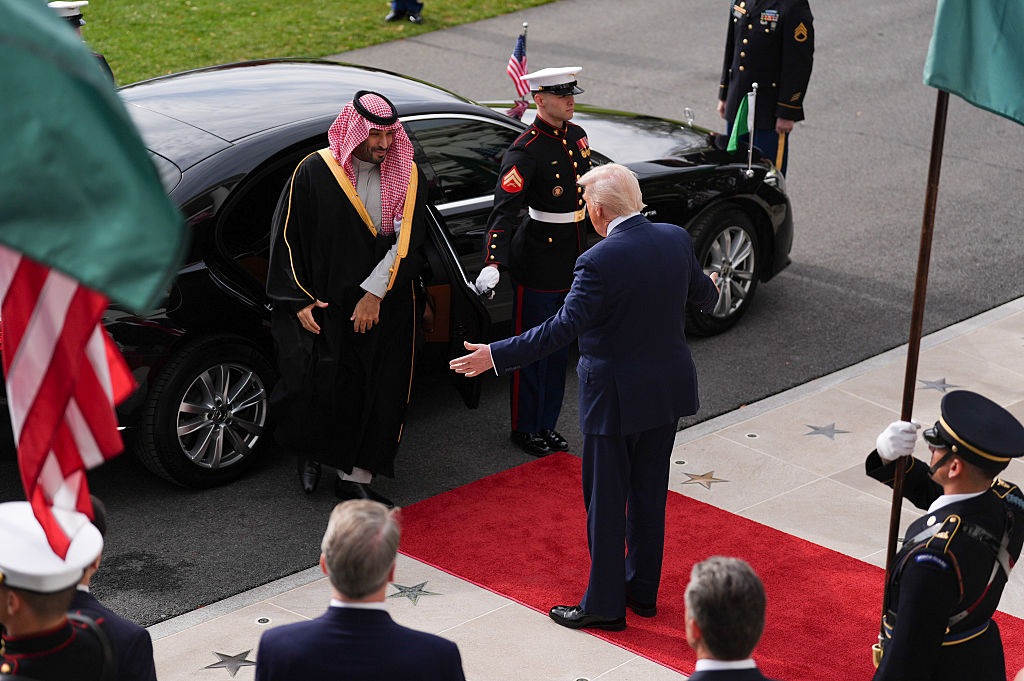

Since September alone, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia, President Ahmed al-Sharaa of Syria, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey, and Prime Minister Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman al Thani of Qatar have visited the United States for talks with President Trump. These visits acknowledge the centrality of the U.S. role in regional affairs and illustrate how the region’s power elite is adapting to Trump’s America.

Over the past decade, mirroring the global conversation, the idea that the Middle Eastern countries were embracing a multipolar approach in their geopolitical and geo-economic relations has gained prominence. The region has become unmistakably multipolar in terms of its economic, technological, and strategic infrastructure. China has become the Gulf’s largest trading partner, surpassing the U.S., the U.K. and the Eurozone. Huawei, the Chinese telecommunications firm, now plays a central role in sensitive technology and 5G networks across every GCC state.

To counter growing Chinese regional influence, in 2023 the U.S. and the EU backed the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor, a project designed to link India to Europe by sea and rail connections through the Gulf, Jordan, and Israel. (The project has since been stalled by the war in Gaza.) Meanwhile, most Middle Eastern countries remain part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative and are signing up to alternative trade corridors such as the Iraq Development Road project, a joint venture by Iraq, Turkey, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates. Yet this increasingly multipolar landscape doesn’t extend to regional security.

America, the indispensable

The war in Gaza has demonstrated that no other power—whether China or Russia—has come close to replacing the U.S. in the Middle East. On questions of war and peace in the region, all roads still lead to Washington. Without U.S. pressure and insistence, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu wouldn’t have apologized to Qatar for the strike on Doha or agreed to a ceasefire in Gaza. Similarly, without U.S. acquiescence, the al-Sharaa government in Syria would not have international legitimacy or realistic prospects for reconstruction, which depend on Washington moving toward permanently repealing the Caesar Act sanctions. For now, these sanctions have only been waived for 180 days.

The indispensability of American power means that, in the short term, the regional states will double down on their ties with Washington. After Israel’s September attack on Doha, Qatar pursued more robust security relations with Washington, and President Trump signed an extraordinary executive order that committed the U.S. to “take all lawful and appropriate measures, if necessary, military,” to defend Qatar in the event of an attack against the country. Though it is not a treaty-based defense alliance, the security pact came close to resembling the NATO mutual defense clause.

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who met Trump at the White House on Tuesday promised to increase Saudi investments in the U.S. to close to a trillion dollars and sought a stronger security partnership between the Kingdom and Washington. Trump offered major non-NATO ally status and pledged the sale of advanced AI chips and F-35 stealth fighters to the Kingdom. Though it is yet to materialize, Saudi and U.S. officials have been discussing a mutual defense pact.

For years, Turkey bristled at the U.S. military presence in Syria because of Washington’s partnership with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, which Ankara regards as an offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), the group that waged a decades-long insurgency against the Turkish state. In the summer, Turkey and the PKK resumed a peace process after the militant group agreed to disarm and dissolve itself. Anxious about what it sees as Israel’s revisionist policies and military aggression in Syria, Turkey has once again turned toward Washington as it sees the U.S. as the sole power that can constrain Israel.

America, the unreliable

Yet a strong perception of American unreliability lingers in the region. The sense of stability in the Gulf Arab countries was shaken when Iran fired ballistic missiles at the Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar in retaliation for the U.S. joining Israel’s war against Tehran and bombing Iranian nuclear facilities. And, in September, U.S. security guarantees did not prevent the Israeli strike on Doha. Earlier, in Sept. 2019, when Iran-backed Houthi rebels targeted oil facilities in Saudi Arabia with drones, the American response fell short of expectations in the Kingdom.

Arab states are also skeptical about the nature of their security relationships with the U.S. and doubt the credibility of American commitments, because their security partnerships with Washington are partly tied to the state of their relations with Israel. For instance, Saudi Arabia was hoping for a formal defence treaty with the U.S. But such a treaty-based alliance requires approval from the U.S. Senate, which is unlikely to be granted unless the Kingdom agrees to join the Abraham Accords and normalize relations with Israel.

Prince Mohammed expressed his willingness to join the Abraham Accords but linked this to a clear path toward the establishment of a Palestinian state. Given the broad Israeli opposition to Palestinian statehood, the prospect of Saudi–Israeli normalization remains off the table for the foreseeable future. Saudi Arabia might have to limit its ambitions for a defense treaty with Washington.

In the past year, the Gulf countries have increasingly come to see Israel’s military expansionism as a threat. The logic that their relations with the U.S. are conditional upon the state of their relations with Israel is likely to encourage them to pursue alternative strategies. Indeed, a week after Israel’s attack on Doha, Saudi Arabia signed a mutual defense pact with nuclear-armed Pakistan.

The sense of American unreliability, combined with the belief that relations with Washington are conditional upon their relations with Israel, is likely to lead most Middle Eastern states to pursue diversification strategies in their defense industries and security partnerships in the mid to long term. Most Middle Eastern states are likely to deepen their ties with Beijing.

The existence of multiple centres of power does offer multiple choices, but these different power centres, or poles, do not hold the same significance. The United States remains the most significant and preferred partner for most Middle Eastern states in their security partnerships and defense procurement. America’s failure to uphold its security commitments would damage its standing in the region and hasten the regional search for strategic diversification, with both regional and global implications.