The age of trade protectionism returned to America in 2025 with the shudder of a closing customs gate. President Donald Trump has long professed his love of tariffs, once calling them “the most beautiful word” in the dictionary. In February 2025, barely a month into his second term, Trump breached the trade agreement he himself negotiated with Canada and Mexico in 2018, and imposed new tariffs on both countries. In February and March 2025, he moved to impose tariffs on China.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

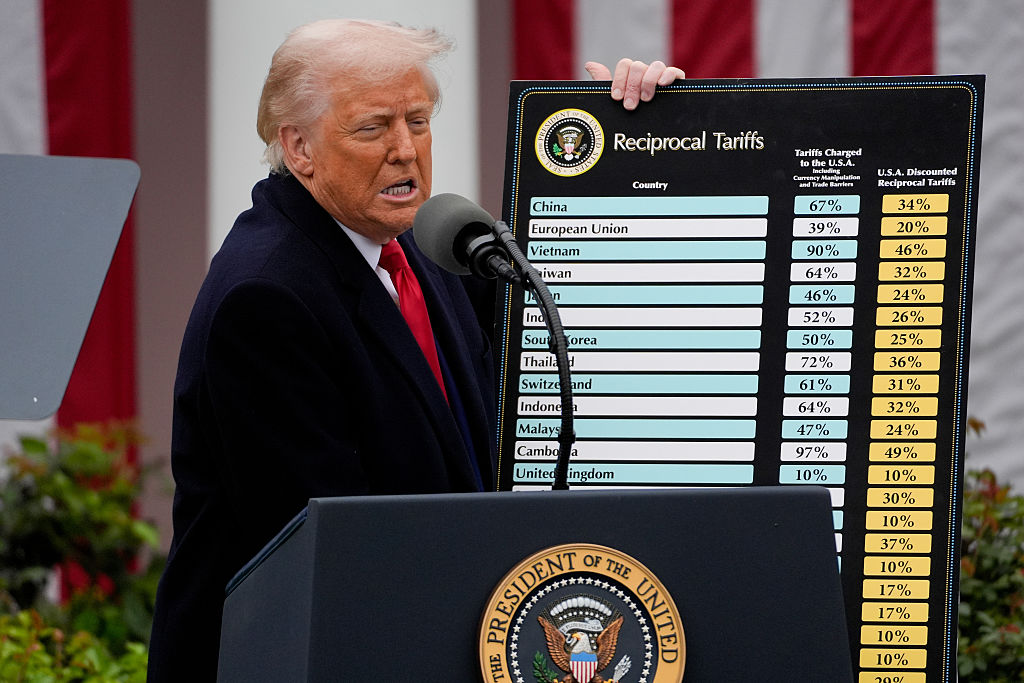

April 2025 turned out to be the cruelest month: Trump announced tariffs on imports from virtually all countries. Those tariff actions were shocking not only because Trump invoked a law that no other president had used to impose tariffs, but also because he raised rates—on adversaries and allies alike—to levels unseen since the 1930s.

Americans noticed and began acquainting themselves with the world of tariffs. Internet searches for “tariff” noticeably trended up throughout 2025 and the word entered daily conversations and supermarket aisles. But tariffs aren’t new. Tariffs are one of the oldest tools of American economic policy.

After its birth as a nation, the United States used tariffs to ensure a steady flow of revenue to finance its government and support its infant industries. After the Civil War, the U.S. didn’t rely heavily on tariffs to generate revenue but used them to protect domestic industry—northern industrialists and Midwestern farmers—from European competition. For years, Congress set tariff rates item by item, and the debates over each line were susceptible to capture by special interests.

The pattern was on blatant display in the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930: conceived to protect farmers, it quickly expanded into something larger. The economic disruption that followed forced a rethink of trade policy, and Congress responded by ceding more authority to the President. Democrats and Republicans continued squabbling over the content of trade policy, but the protectionist impulse largely receded and was replaced by a consensus that lower trade barriers would support economic recovery and advance broader foreign policy goals. Today, that consensus has reversed.

A bipartisan shift toward trade protectionism in the United States came about in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the rise of China, and the fading of America’s unipolar moment. Unlike earlier periods of protectionism, this new chapter was not triggered by a single external economic shock so much as by the accumulation of domestic anxieties.

The first Trump Administration’s move to raise and entrench tariffs in 2017, justified in the name of “economic security” marked the start of this era. President Joe Biden largely followed the same course. The trend is likely to continue unless it results in significant and persistent economic pain and political backlash.

Old tools for new threats

At the start of President Trump’s second term, the average U.S. tariff rate stood at roughly 2.4 %. Today, the overall effective tariff rate is 16.8 %, the highest it’s been since 1935, according to the Yale Budget Lab. While the scope and scale of tariffs was comparably smaller in his first term in office, Trump did start a trade war with China, and slapped tariffs on steel and aluminum, while threatening many others. President Biden kept most of the tariffs on China and others in place, but he also added tariffs on electric vehicles, solar cells, and battery parts. Since his return to the White House, Trump has expanded trade protection to unexpected levels, and in a dizzying way.

A common thread between the Trump and Biden years is a “paradigm shift” in thinking about U.S. foreign economic policy, one that fuses national security interests with economic ones. The term “economic security” is increasingly used in Washington to describe the use of economic tools as leverage to achieve certain domestic and foreign policy goals. Much of the narrative on economic security is fueled by fears of China’s rise, and the belief that economic interdependence poses a threat to U.S. hegemony in the world. Export controls, industrial policy, trade barriers, and strategic foreign investments all play a role in this policy toolkit.

The idea of using economic tools to support U.S. national security interests has a long history, but the concept of national security has become more expansive today. Politicians are no longer just concerned about armed conflicts or terrorism. Energy security, food security, climate change, and public health have all been elevated to essential security concerns. This expansive conception of national security goes to the heart of the slippery logic of economic security—a term so broadly defined that it threatens to become a catchall for the general welfare of the American people. In the process, this understanding fails to distinguish between legitimate economic security concerns and trade protectionism, because, under such a definition, everything is potentially a threat.

Debates about the use of tariffs to advance general welfare date to the Republic’s early years. In 1824, Henry Clay, the era’s most persuasive apostle of congressional power, proposed high, across-the-board tariffs to reduce dependence on imports, shield young American industries from British competition, and support the development of a reliable domestic “home market” for American farmers and manufacturers. It was a major call for nation-building.

Thomas Jefferson, who had retired in 1809, was living at Monticello, and working toward establishing the University of Virginia, felt compelled to respond. In a letter to his friend James Madison, he shared a draft proposal for the Virginia General Assembly, warning that Clay’s proposals amounted to abuse of Congress’ constitutional powers. The Constitution, he argued, did not grant lawmakers “the power to do whatever they may think, or pretend, would promote the general welfare… without limitation of powers.”

Madison and Jefferson were not doctrinaire opponents of tariffs; they supported some modest and temporary tariffs. But Clay’s sweeping tariffs, they believed, went too far—interfering with the spirit of free enterprise and failed to represent the diverse industrial interests in the country. They feared that such tariffs would drive up the costs of imported goods Americans would buy anyway, since many of those products were not produced domestically. And they foresaw high tariffs would invite a perverse scramble among favored industries for additional protection.

Over the years, Congress ceded much of its power over trade policy to the president

in the hope that the executive branch would better represent national interests over the parochial concerns of Congress. While Congress still retains the power to regulate trade, and develop clear objectives for trade policy, the arrival of the age of economic security threatens to diminish this role. The central theme of President Trump’s 2017 National Security Strategy was “economic security is national security.”

This braiding of economic and national security has, in practice, meant that presidents have expanded their influence over the economic lives of Americans, often without congressional oversight. Trump has argued that Congress handed over its authority to regulate commerce with foreign nations through a series of laws—laws that he has used to impose tariffs. Biden, for his part, claimed that the Constitution itself confers upon the president broad discretion to negotiate trade deals without congressional input.

Many presidents have invoked national security to justify executive action across a range of policy areas, but its encroachment into the economic sphere minimizes the checks and balances that have traditionally played an important role in debates over economic policy. If a president can take any action so long as it can be tethered, even tenuously, to national security—including imposing trade restrictions on mundane things like beer cans and furniture—what meaningful limits remain on his power? Trump’s penchant for wielding emergency powers and national security rationales to take trade action has shone a spotlight on this problem. Yet Congress has done little to challenge it.

An inconvenient truth

Over the past several months, the Trump Administration’s focus on signing deals to reduce the highest tariff rates imposed on Trump’s “Liberation Day” suggests a wrinkle in the administration’s national security rationale. If punishing tariffs are supposed to protect Americans, why would the administration agree to lower them at all? From the outset, trade experts raised the alarm on Trump’s tariff policy and warned that such high trade barriers would have significant negative consequences on the U.S. economy.

Trump floated several different tariff figures—from 10 to 100 %—before raising the average U.S. tariff to 1909 levels (22.5 %). The move sent stock markets tumbling. He quickly backtracked, and claimed that the threat was simply a tactic to bring countries to the negotiating table and compel them to lower their trade barriers. As a result, tariff rates are nowhere near the levels Trump announced in April, and their impact was more limited than feared, as companies had braced for something much worse.

Consider the tariffs Trump imposed on Canada and Mexico in February: lower rates were swiftly secured for fertilizer and energy, out of fear that these measures would hurt American farmers. Trade that complied with the 2018 U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade agreement was also exempted. In total, nearly 46 % of U.S. imports have been exempted from Trump’s tariffs. The sheer breadth of these exemptions reveals the shallowness of the national security rationale the Trump Administration invoked to justify the tariffs.

The price of tariffs

The wide-ranging tariff exemptions suggest that a large chunk of U.S. imports provide economic benefits, and that the United States does not face equal risk from its interdependence with every trading partner. The Biden Administration, to a degree, recognized the imperative to work with allies to advance economic security objectives, but it did so while harboring deep skepticism toward trade as an instrument of bolstering American economic opportunity.

The second Trump administration is even more distrustful. But has this skepticism strengthened U.S. economic security? So far, there is no evidence to suggest that the tariffs have made the American economy more secure. In fact, economists estimate that if Trump’s tariffs stay in place, the U.S. will have slower economic growth, higher prices, and lower employment over the coming decade.

Those hit hardest by tariffs are small businesses, which make up 97 % of U.S. importers. In September, they shed 40,000 jobs. These businesses have a harder time navigating erratic policy shifts. They also don’t have the ability to absorb all the costs like big firms, or to negotiate with suppliers. This leaves them with little option but to raise prices. And, those that search for alternative, American sources for their products, often can’t find or afford them.

Consumers will also feel the pinch. While businesses front-loaded imports, they held off on raising prices because of fluctuations in Trump’s tariff policy. But, as tariffs have begun to settle, their costs have been increasingly passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices. While only 37 % of those costs were passed on to consumers up until August, Goldman Sachs estimates that 55 % of the tariff costs are expected to be paid by consumers by January. It’s no surprise that Americans are anxious about the economy and losing their jobs.

American allies are also anxious about whether they can count on the U.S. at all. Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney described the U.S. as “no longer a reliable partner,” and ramped up efforts to diversify Canada’s trade links. Canada is reportedly considering Swedish-built fighter jets over American ones. French President Emmanuel Macron voiced similar sentiments, urging European partners to “guarantee our own security.” These expressions of concern reflect growing unfavourability of the U.S. around the world. If this rift is not temporary, it will be difficult to leverage those partnerships to support American interests in the future.

The Trump Administration’s use of tariffs as a tool to bolster economic security has therefore yielded little payoff. It has also moved debates over trade and tariffs away from Congress and concentrated that power in the hands of the executive branch under the banner of national and economic security. Yet tariffs have made Americans neither more secure nor more prosperous. And the piecemeal trade deals being negotiated now are unlikely to fare any better.

The question that lingers is how long Americans will put up with government intrusions into their lives to serve vague notions of economic security. In the meantime, tariffs will persist, their economic effects will ripple throughout the economy, and America will have fewer friends around the world.