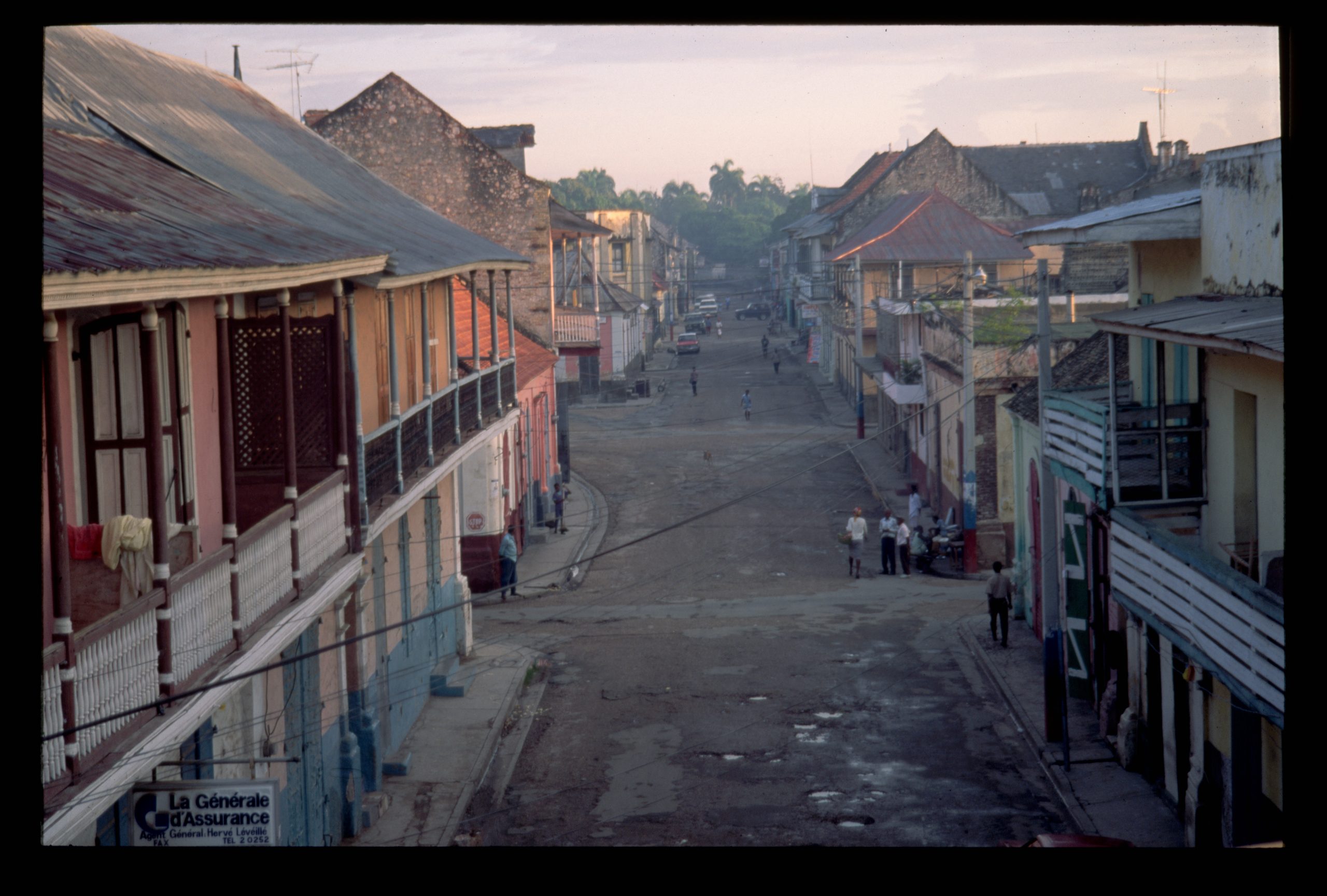

The sounds of Cap-Haïtien, Haiti, historically referred to as “the Paris of the Antilles,” are inimitable.

One night, I could have sworn I heard a man turn into a werewolf. My skepticism kept me from truly believing it, but when I heard a man yell as though he were being exorcised, combined with the barks of dogs superimposed over his suffering, I understood the folklore of Haiti’s countryside. It not only sounded supernatural, it felt that way. I had a nightmare that night.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

When you’re from Haiti, you know that roosters don’t only cock-a-doodle-doo in the mornings as they do in cartoons. They remind you of their existence throughout the day. I find it refreshing and calming to be around this sort of animal life. I also hear gunshots and goats bleating. I hear church music projecting across neighborhoods and young boys getting chastised by their mothers. The singing of a congregation’s cry floats over me, though I am miles away. Drums, ocean waves, men arguing about who would take me to Île-à-Rat. The sounds of Haiti, as I experience them, all at once, are one of a kind.

In Haiti, the sounds of the purportedly supernatural are mixed with the scents of gasoline—diesel that’s still poured into jugs in order to transport. The smell of burnt charcoal, used to cook. The enduring scent of burning garbage, used as one of the sole means of ridding neighborhoods of their trash. Heavy rains add to Haiti’s perfume. But they also cause floods that cars have to drive through, and, if carless, people must walk through.

Haiti is both beautiful and dangerous—and it is unfortunately unsafe for many.

But Haiti didn’t become this way by happenstance. It has been, and continues to be, impacted by systemic and strategic forces—namely, the United States.

America’s pernicious relationship with Haiti comes to a head once more this week. President Donald Trump has tried to revoke Haitians’ access to Temporary Protected Status (TPS), one of the few opportunities for reprieve for Haitians who sought safety in the United States. When Secretary of Homeland SecurityKristi Noem announced the termination of Haiti’s TPS designation, she suggested that it is currently safe to return to Haiti. But this is not the case.

The Trump Administration posted a termination notice at the end of November 2025, giving Haitians living in the U.S. with TPS about two months to return to a new country. On Feb. 3, 2026, TPS for Haitians was set to expire, putting more than 330,000 people at risk of deportation. Then, at the final hour, a federal judge paused Trump’s plans for now.

The Trump Administration’s attempted elimination of the 15-year-old program was expected to not only negatively impact the local economies that rely on Haitian workers but also to devastate families. The move would be both economically irrational and morally obtuse. It is also part of a long pattern of injustice towards Haiti.

In the 222 years since declaring its independence, the Caribbean country and its people has consistently found itself as the target of American derision—from Thomas Jefferson’s refusal to acknowledge Haiti’s independence to Trump’s inaccurate depiction of Haitians. Haiti’s position in the Caribbean Sea primed it for slavery in Jefferson’s era, and has been prime for exploitation in Trump’s era.

To be sure, it would be elementary to solely blame the Trump Administration—or any one administration—for Haiti’s centuries-long issues.

Haiti liberated itself from France in 1804. After which, France imposed an indemnity for the loss of “property” (read: formerly enslaved people). In 1947, Haiti finally paid it off. Money that would have gone to basic infrastructure was sent to the people who caused the destruction in the first place.

The United States only made matters worse. First, the U.S. placed an embargo on the newly freed Haiti, which prevented it from participating in international trade.

Then, in 1856, the U.S. Congress passed the Guano Islands Act. The following year, a U.S. ship landed on the Haitian territory of Navassa and claimed that the Guano Islands Act gave the U.S. the “right” to control Navassa. In response to resistance, the U.S. Navy parked a warship in the harbor of Port Au Prince. Navassa became U.S. territory. It still is.

From 1915 to 1934, the U.S. occupied Haiti. During this 19-year rule, the U.S. changed Haiti’s Constitution, secured ports and commercial districts, and created powerful political positions that they filled themselves. The U.S took control of Haiti’s national bank, government, and media industry.

But even after America’s formal occupation, its interference continued. In 1990, democratically elected Jean-Bertrand Aristide won. One of his attempts at reform was to raise the minimum wage from 25 cents to 37 cents. USAID refused.

And after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, the United States withheld critical aid, with relatively few funds actually reaching Haitians.

These are just a few examples that represent the perpetuation of poverty in Haiti. Unfortunately, it is not an exhaustive list of the underdevelopment wrought on the island country. But as I walk through my neighborhood in Brooklyn, where my parents immigrated to, I think of the home my family developed in America.

I think of the clothing lines in Au Cap, freshly washed clothes drying in the sun. They reminded me of my basement growing up—a place where my mother refused to use any machine that would drive the bills up. We had to duck and dive when we were down there. It was a semblance of her first home. It was a reminder of how immigrants like my parents made things work. It reminded me of the Haitians living in the U.S. through TPS who have borrowed America’s promise of justice, fairness, and opportunity.

Haitians are yearning for this promise and for a home. They can’t go back due to gun trafficking and violence in the streets. Haitians require somewhere safe.

The United States has an obligation to give that to them. Haiti’s underdevelopment is a direct result of the United States. TPS is the least we could do.