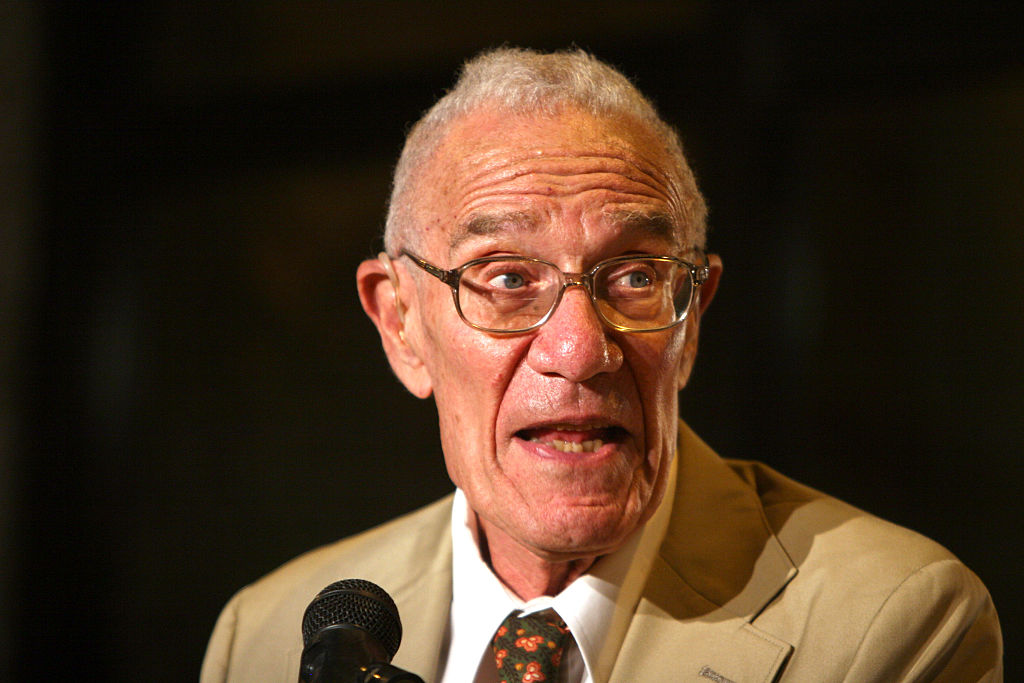

Robert Solow, an economics professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who won a Nobel Prize for his analysis of how technology drives economic growth in developed nations, has died. He was 99.

Solow died on Thursday at his home in Lexington, Massachusetts, the New York Times reported, citing his son.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded Solow the 1987 Nobel in economics for developing a mathematical model for expanding production, part of a field that became known as growth accounting. “Solow’s growth model constitutes a framework within which modern macroeconomic theory can be structured,” the Nobel organization said in announcing his award.

In a series of articles published from 1956 to 1960, Solow had demonstrated that prevailing growth models were inadequate because they focused narrowly on increases in capital and labor.

“The interesting thing that came out of my work,” he told the Chicago Tribune when he won the Nobel, “was that the change in technology — the progress of science, engineering and technology — accounted for half, at least, of all the growth we had in the economy.”

How to quantify that was a challenge for economists. “I thought from the very beginning and still think now that there is an element of sheer chance in technological innovation that we’ve come nowhere near catching,” he said in a 2002 interview with the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

Samuelson’s partner

Like his friend and MIT research partner, Paul Samuelson, who won the economics Nobel in 1970, Solow advocated an active role for government in managing the economy through tax policy and spending, a line of thinking associated with British economist John Maynard Keynes. Nobel Committee President Assar Lindbeck said Solow’s analysis helped persuade leaders of industrialized countries to devote more resources to education and scientific research.

Solow had a chance to implement his theories as senior economist to the Council of Economic Advisers under President John F. Kennedy. He won his Nobel during the administration of President Ronald Reagan, whom he criticized for pledging never to raise taxes.

At the press conference after receiving the award, he said: “The best thing you can say about Reaganomics is that it probably happened in a fit of inattention.”

Solow contributed a chapter to the 2017 book, After Piketty: The Agenda for Economics and Inequality, a follow-up to Thomas Piketty’s much-discussed 2014 treatise on wealth inequality, Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

In his chapter, titled “Thomas Piketty Is Right,” Solow called the widening gap between the rich and the non-rich an “ominous anti-democratic trend.” He endorsed Piketty’s call for an annual progressive tax on wealth but added the caveat that such a tax stood little chance of being enacted in the U.S., where “we are politically unable to preserve even an estate tax with real bite.”

Harvard scholarship

Robert Merton Solow was born in Brooklyn, New York, on Aug. 23, 1924, the first of three children. His father, Milton, was an international fur buyer.

Solow attended New York City public schools and won a scholarship to Harvard University, starting in 1940.

He left school in 1942 to join the Army and served in North Africa, Sicily and Italy until World War II ended in 1945. Back at Harvard, he delved into economics and became research assistant to Wassily Leontief, the Russian economist who would win the Nobel in 1973.

Solow earned his undergraduate degree in 1947, his master’s in 1949 and Ph.D. in 1951, all from Harvard. He joined the MIT faculty in 1950 with plans, he later said, to spend his career teaching statistics and econometrics.

“I was given the office next to Paul Samuelson’s,” he wrote in an autobiography for the Nobel Foundation. “Thus began what is now almost 40 years of almost daily conversations about economics, politics, our children, cabbages and kings. That has been an immeasurably important part of my professional life. I suppose it was inevitable that I should drift back into ‘straight’ economics, where I discovered an instinctive macroeconomist struggling to get out.”

Samuelson died in 2009.

Taught Draghi

Solow’s students over his many years at MIT included Mario Draghi, who would go on to lead the European Central Bank and serve as Italy’s prime minister.

The American Economic Association in 1961 awarded Solow the John Bates Clark Medal, which recognizes the most significant contributions by an American economist under 40.

Solow spent 1961 and 1962 in Washington on the staff of Kennedy’s Council of Economic Advisers. Led by Chairman Walter Heller, the group of economists developed the economic policies of Kennedy and his successor, Lyndon Johnson.

From 1975 to 1980, he served on the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. He was a founding director and chairman of the Manpower Demonstration Research Corp., which was created to test the effectiveness of policies aimed at helping the poor.

He retired from MIT in 1995, becoming professor emeritus.

With his wife, the former Barbara Lewis, an economic historian who died in 2014, he had three children: John, Andrew and Katherine.