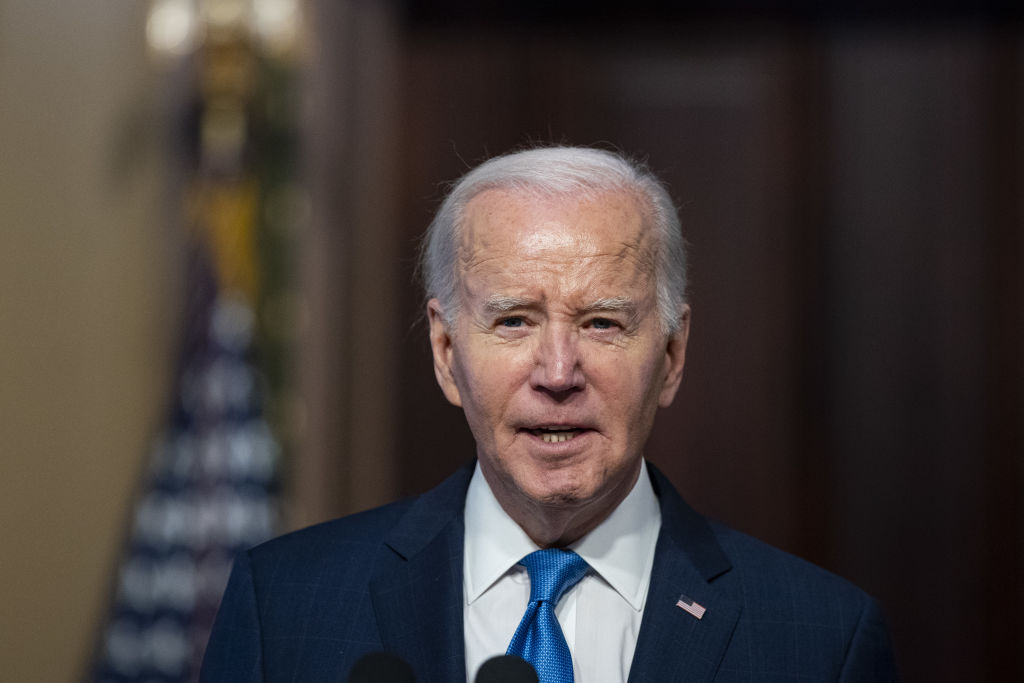

It was 100 days into his presidency and President Joe Biden was touting his accomplishments at a rally in Georgia when protestors started shouting him down and telling him to close the country’s privately-run immigration detention centers.

“I agree with you. I’m working on it man,” the President said in response. “There should be no private prisons period. None, period. That’s what they’re talking about, private detention centers. They should not exist and we are working to close all of them,” he said. Biden’s pledge, three months into his presidency, echoed a campaign promise he made to prevent businesses from profiting off of the suffering of people fleeing violence to come to the U.S.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

And at the end of Biden’s third year, his administration is still heavily reliant on for-profit companies to run immigration detention centers. Some 90% of people held in immigration detention are in facilities run by private companies, according to an analysis by the ACLU.

Since Biden came into office in January 2021, those held in immigration custody has more than doubled from 14,195 on Jan. 22, 2021 to 36,755 on Dec. 3, 2023, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), a research institution at Syracuse University that collects and analyzes federal immigration data. While those figures are less than the peak immigration detention figures at 55,000 hit under the Trump administration in 2019, the trajectory reflects the spike in migration rates in the Biden era, after slowing during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the administration holding more immigrants in custody while their asylum cases play out.

Biden is under pressure from Republicans in Congress to shut down legal asylum and parole pathways in ongoing negotiations over funding for border security, making it unlikely Biden will be able to change course before next year’s election on his administration’s reliance on private companies in immigration detention.

“The evidence is quite clear that President Biden has failed to fulfill his campaign promise and in fact has back-tracked in terms of the use of immigration detention,” says Eunice Cho, the senior staff attorney at the ACLU’s National Prison Project. “The number of people detained in ICE detention has expanded rapidly under the Biden administration.”

Biden’s campaign promise to end using private facilities for any detention, including immigration detention, is “unmet,” agrees Lauren-Brooke Eisen, senior director of the Justice Program at the Brennan Center for Justice and author of the 2017 book “Inside Private Prisons.” Biden has run into a major hurdle in just how intertwined the private prison industry is with how the country detains people while their immigration cases are being heard. “The challenge there is that most of the ICE detention centers are owned and operated by for-profit firms,” says Eisen.

In Biden’s first week in office, he issued an executive order that directed the Department of Justice to not renew contracts with privately-operated criminal detention facilities. Dena Iverson, a spokeswoman with the Justice Department, said the agency was continuing to work to implement the order, noting that the Bureau of Prisons and US Marshals Service had terminated contracts with over a dozen privately-owned providers.

Yet while that order has led to a reduction in use of for-profit companies in federal detention, it notably did not apply to immigration detention, allowing Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to continue to rely heavily on for-profit companies.

The immigration system’s reliance on for-profit detention centers goes back decades. As ICE built out its network of detention centers for holding people facing possible deportation, the federal government decided not to build large numbers of its own facilities, says Eisen at the Brennan Center. “The government never really invested in or built its own detention centers. It outsourced that to these for-profit firms,” Eisen says.

The logistics of migrant housing is complicated, as the funding available and the beds needed change from year to year, according to Corey A. Price, the executive associate director for Enforcement and Removal Operations at ICE. Contracting with private companies allows ICE to bring on new detention beds quickly when Congress allocates more funds, he says.

Ryan Gustin, a director of public affairs at CoreCivic, a for-profit detention company that contracts with ICE, says that the company “plays a valued but limited role in America’s immigration system, which we’ve done for every administration – Democrat and Republican – for nearly 40 years.” Federal government agencies “often choose to work with us because of the flexibility we can provide, which is particularly important when their needs and priorities can change significantly from year to year,” Gustin says.

But running prisons as money-making businesses can incentivize private companies to cut corners, says Jennifer Ibañez Whitlock, a supervisory policy and practice counsel at the American Immigration Lawyers Association. “The profit motive really drives down the safety and the security in those facilities,” says Whitlock, who adds that for-profit detention centers have a pattern of being understaffed. “The whole system works to do this at the cheapest available rate,” she says.

A spokesperson for a group representing the private prison industry pushed back against the notion that their facilities are unsafe. “Contractors are held to strict federal standards, which were updated and strengthened under President Obama,” says Alexandra Wilkes with the Day 1 Alliance. “Everything from health care services to access to attorneys and immigrant rights advocates are provided. Without this critical infrastructure, migrants would likely be housed in overcrowded local jails alongside potentially dangerous people.”

Price adds that ICE reviews facilities to ensure they are not falling short of federal guidelines. “We may need the beds, but it is not worth the risk of continuing to contract with them if they are not meeting our standards,” he said.

ICE announced in March 2022 that the Biden Administration would stop using the Etowah County Detention Center in Gadsden, Alabama, a county facility that is operated by a private company, and would reduce its use of three other facilities in Florida, Louisiana and North Carolina. ICE announced at the time that the Etowah County Detention Center had “a long history of serious deficiencies” and was of “limited operational significance” to immigration officers.

Months after Biden’s executive order in 2021, a privately run prison in Philipsburg, Pennsylvania called the Moshannon Valley Correctional Center shut down after the Federal Bureau of Prisons did not renew its contract. But within a year, the prison had reopened under a new name, the Moshannon Valley Processing Center, and under a new contract for immigration detention with ICE. On Dec. 6, a Cameroonian man named Frankline Okpu died at the Moshannon Valley detention center, according to ICE.

“This administration, in the most generous light, over-promised what they were going to do or could do to deal with the problem of private detention and, in the worst light, just have completely abandoned those efforts,” says Whitlock.