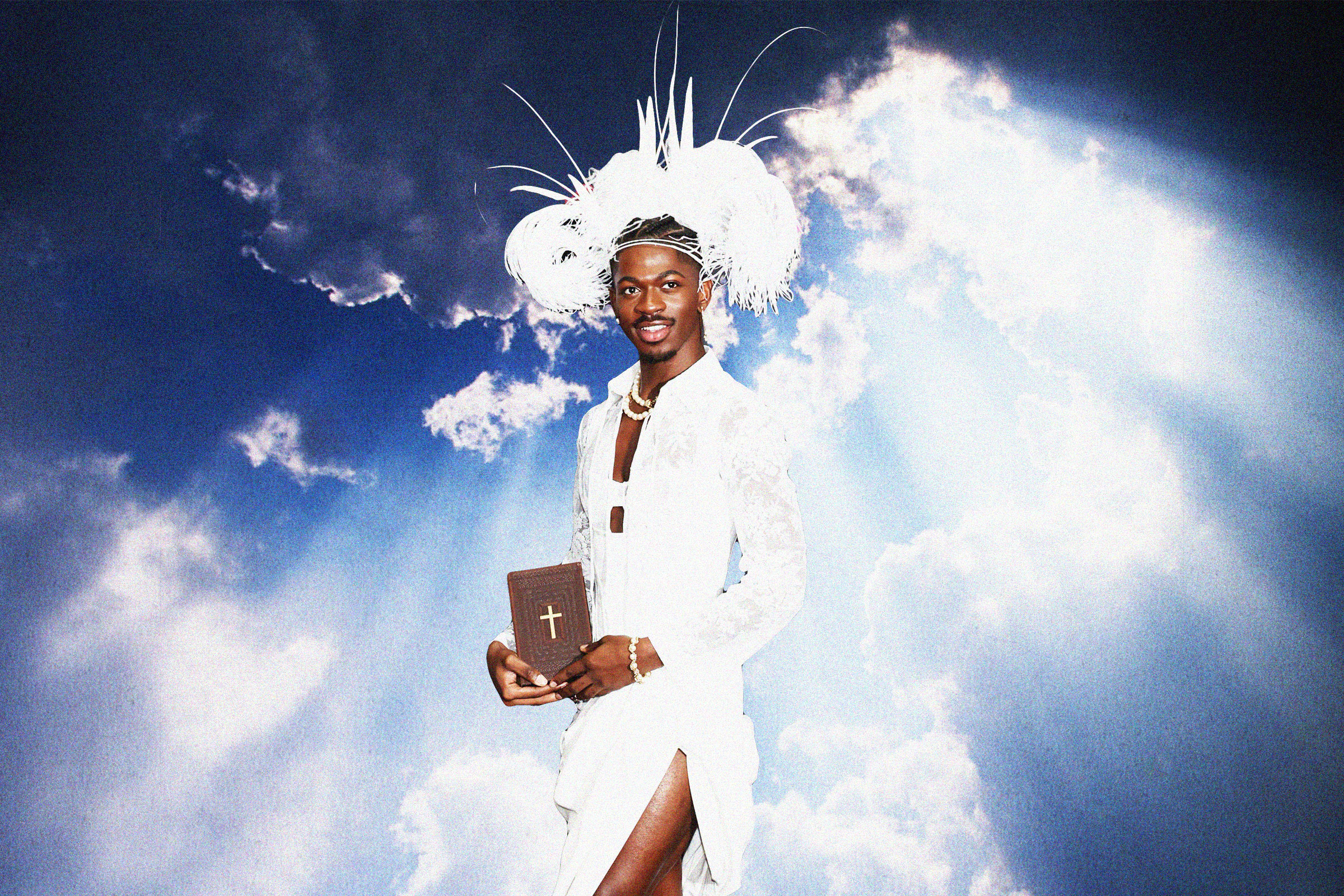

Lil Nas X’s new single “J-Christ” is the rapper’s latest moment of invoking a religion that has not always welcomed openly gay people like himself. It’s clear the artist sees himself as a martyr—a photo Lil Nas X posted on X (formerly Twitter) announcing the song featured him lying on a cross.

“MY NEW SINGLE IS DEDICATED TO THE MAN WHO HAD THE GREATEST COMEBACK OF ALL TIME,” he wrote.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Lil Nas X has always embraced provocative Christian imagery. The biggest example is the lap dance he gave a devil character in the 2021 music video for “Montero.” In TIME’s 2021 cover story about the artist, he explained that he is trying to reach certain people who have felt like sinners and outsiders at church, specifically LGBTQ youth.

“I grew up in a pretty religious kind of home—and for me, it was fear-based very much,” he told TIME. “Even as a little child, I was really scared of every single mistake I may or may not have made. I want kids growing up feeling these feelings, knowing they’re a part of the LGBTQ community, to feel like they’re O.K. and they don’t have to hate themselves.”

Lil Nas X releases “J-Christ”

In “J-Christ,” which released Friday, Lil Nas X compares himself to Christ coming back from the dead, to stand up for the LGBTQ community. “Back-back-back up out the gravesite. B-tch, I’m back like J Christ. I’m finna get the gays hyped.”

Delvyn Case, professor of music at Wheaton College (Massachusetts) who maintains a database of Jesus mentions in popular songs, notes that Lil Nas X is suggesting that just as Christ was persecuted, LGBTQ people are persecuted by many Christians because of their sexuality. “He’s probably been used to having Christians persecute him for his whole life,” Case says. “But he—rightly, in my opinion—is commandeering that imagery and showing that it doesn’t belong to just them.”

The music video begins with actors impersonating celebrities ascending into heaven, including Barack Obama, Kanye West, Mariah, Ed Sheeran, Taylor Swift, and Dolly Parton. In one scene, he is playing basketball against the Devil and wins by making a slam dunk to represent his comeback. In another scene, he is nailed to a cross, wearing a crown of thorns, while people in white cheer for him like they’re in a mosh pit at a concert. At first the cross is upside down, which can be seen as representative of his LGBTQ identity clashing with anti-gay Christian fundamentalists.

Reaction to Lil Nas X’s new single on the social network X was largely positive. One user, @DavideLNX, said that the music video is signaling a new stage of the musician’s career, arguing, the song marks a “transition between two eras” for the artist.

“The music video brings back Satan to connect to the Montero era and ends with Noah’s Arc and flooding everything to represent that all that is over and it’s time for a new beginning. I love the concept.” Another user @kingbarbiebishy poked fun at the criticism that he is mocking Christ, writing that Lil Nas X is doing “what he does best[,] get a rise out of y’all.”

Case agrees, noting that “J-Christ” represents a comeback of sorts in that it’s Lil Nas X’s first song release in about two years. “Based on the lyrics and what he said in articles before the release, he’s identifying himself with Jesus for the other reason: to brag,” he says. “Many rappers liken themselves to Jesus by referring to examples of his power: whether it’s to perform miracles, or command crowds, or, most significantly, to defeat death. Here, it’s pretty simple—Lil Nas X hasn’t released a song for 2 years, and now he’s making a “comeback.” And JC made the greatest comeback of all time.”

“J-Christ” and the history of Christian imagery in music

Lil Nas X’s single is the latest in a long history of stars singing about Jesus in secular, popular music.

“The phenomenon of Jesus showing up in secular music really starts with Jesus Christ Superstar,” says Case. “That opened the floodgates. Since then, rock songs and songs in every secular genre have come out with Jesus as a character in some capacity.”

Jesus Christ Superstar, a rock opera produced by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice, debuted on Broadway on October 12, 1971. According to two TIME cover stories on religion published that year (one on a “Jesus Revolution” in June and one on the hit musical in October), the show’s popularity was an example of a larger interest in spirituality that had taken hold as a palate cleanser from the counterculture of sex, drugs, and street protests that characterized the 1960s. How religion would adapt teachings dating back thousands of years to new social mores was top of mind on campuses nationwide.

“Superstar‘s popularity is a symptom and partial result of the current wave of spiritual fervor among the young known as the Jesus Revolution,” TIME wrote in the Oct. 25, 1971, issue. “There is an obvious yearning to consider Christ not merely as a fellow rebel against worldliness and war, but as history’s most persistent and accessible symbol of purity and brotherly love.”

The “Jesus Revolution” cover rattled off the names of artists who have become devout Christians and paved the way for Lil Nas X’s religious songs, like Johnny Cash, Eric Clapton, Paul Stookey of Peter, Paul, and Mary, and Jeremy Spencer of Fleetwood Mac. Another big example at the time was Bob Dylan, who became a born-again Christian in the late 1970s and early 1980s and put out a few albums like Slow Train Coming (1979). Many of the songs he produced during this period are “calling out the church and Christianity for its hypocrisy,” as Case puts it.

Soul music was also growing at the time, represented by artists like Sam Cooke, and virtually all of the big players in this genre got their start in church. The music generally focuses on the persecution of Jesus, and can be a way to educate modern listeners on the past traumas that Black Americans have endured. Braxton Shelley, an associate Professor at the Yale Divinity School, explains the dark history that many of the songwriters make music about as a form of resistance: “One of the really ugly, but quotidian realities was folks leaving white churches on Sunday morning to watch a lynching…So, there is a difference then in the identification with the suffering of Jesus you can expect a Black artist to have.”

In his experience studying Black artists’ references to Jesus in popular music, Shelley says the common themes include “an identification with persecution, being failed by people, people not understanding.” Even if other people don’t get them, Jesus is “someone who does” and urges listeners to look to Jesus as “somebody else who was defeated, but came back.”

Case says that references to Jesus in hip-hop hits grew after Tupac’s “Black Jeesuz,” recorded in 1996. “Jesus basically hardly showed up even as a name check in hip hop before,” says Case. “After that song, so many artists and hip hop artists started to write songs about Jesus.” For example, in Kanye West’s “Jesus Walks” (2004) the rapper makes clear that Jesus stands with the oppressed, “not with the oppressors, not with the slave drivers,” according to Case.

Just as the social movements of the 1960s urged establishment figures to challenge the status quo on issues of race and sexuality and the role of women, hit musicians have been singing about Jesus to get listeners to think about Christian values that contradict one another. In the 1980s, Indigo Girls emerged as a voice for LGBTQ Christians—a precedent for Lil Nas X singing for LGBTQ Christians. In 1991, Genesis’s “Jesus He Knows Me” became a popular sendup of wealthy televangelists. And some artists have even used Jesus to make statements on hot-button political issues. Most recently, at the June 2022 Glastonbury festival, Kendrick Lamar performed his song “Savior” wearing a Tiffany diamond crown and covered in fake blood to voice his dissatisfaction to the U.S. Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade that month.

Ahead of the “J-Christ” drop, Lil Nas X insisted that he is not trying to make fun of Jesus. “Nowhere in the picture is a mockery of jesus,” he wrote on X.” Arguing that crucifixion images are everywhere, and citing the longstanding tradition of religious images in art, he added, “yall just gotta stop trying to gatekeep a religion that was here before any of us were even born.”