White evangelical churches are in crisis. It isn’t just that high-profile leaders have brought politics into the churches, turning evangelicals into warriors for white Christian nationalism and its Republican Party avatars. It is how they have done it. Factions within churches have imposed their values on their fellow worshipers by exploiting the churches’ own processes for resolving disputes and by subverting church democracy. Evangelicals who oppose white Christian nationalism or who think religion shouldn’t mix with partisan politics are running up against powerful structures within their churches. Many of them are leaving church altogether, joining the millions of Americans who don’t claim any religious affiliation. In other words, white evangelicals are facing a double crisis of values and democracy.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

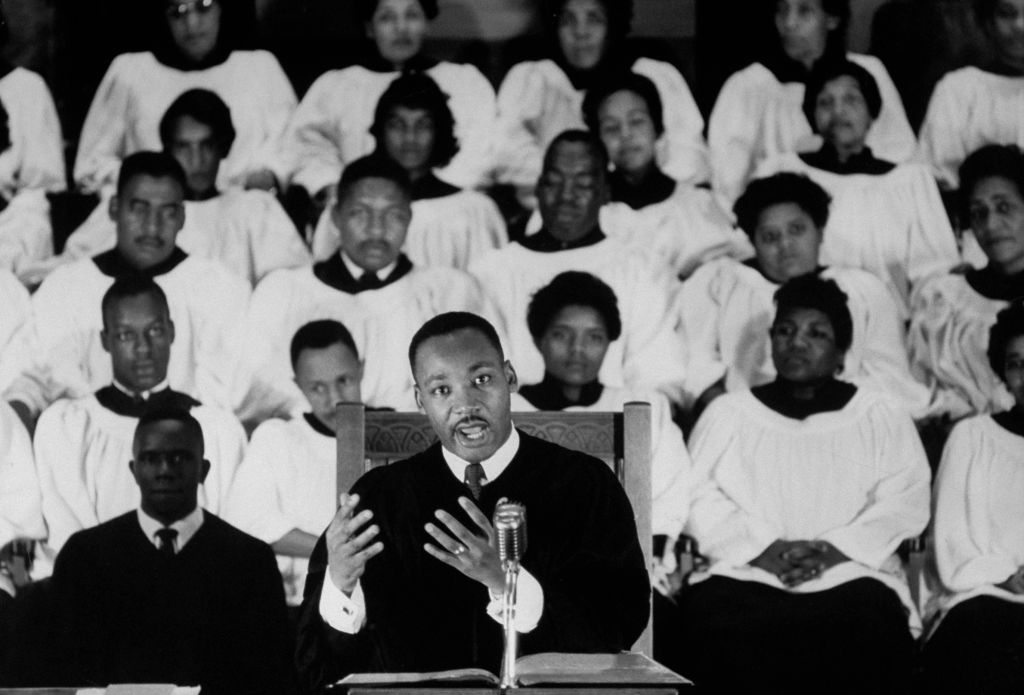

This isn’t the first time American believers have had to grapple with such questions. Sixty years ago, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. used his religious authority and church rules to try to mobilize Black Baptists for what he viewed as the most urgent moral issue in America: Black people’s fight for jobs and freedom—or, as many activists called it, The Movement. What followed was a pitched battle, one that arguably lifted the Movement but tore apart an entire denomination. Now, as the future of both American religion and democracy hang in the balance—as millions of Americans argue over deeply felt moral values—the history of Black churches’ struggles offers both warnings and hope. Not because King was fighting for a righteous cause, but precisely because he and other Black religious people were wrestling with moral questions that had no simple answers.

Although the Black church today is practically synonymous with the fight for racial justice, in the 1950s and 1960s, devout Black Christians fiercely disagreed about whether their churches should get involved. The risks were plain. A church that opened its doors to civil rights activists could lose its valuable tax exemptions, or even be firebombed. But even beyond those physical and financial risks, the hardest problem was the same one white evangelicals are facing today as they contemplate abortion and other issues they view in deeply moral and religious terms: Is a church’s first duty to God or to the affairs of this world?

Black churches had always struggled with this tension. Unlike white evangelicals, Black Christians have never had the luxury of turning away from worldly affairs, because they founded their churches in opposition to a white supremacist church that rejected and reviled them for their color. They had to reconcile their duty to God with what many felt was an urgent duty to “the race.” When racial justice became a mass movement in the 1950s, the question loomed sharper than ever: what is a Black church for?

In fact, Black Christians were fighting on two fronts: against a white supremacist society that denied their rights as citizens and against a church that often denied their rights as members. That tension resonated for many but especially for Black women, who made up more than half the members at most churches and contributed an outsize share of the money, yet could not be deacons or ministers. Indeed, according to the brilliant activist Ella Baker, who worked closely with King, the average Black Baptist minister tended to think of women as ornaments or faithful workers who were there to carry out the minister’s agenda. Under church rules, members had privileges but not rights. This left them vulnerable to what one woman called “church injustice.” It also opened the door to church “dictatorship.” King’s mentor, the Rev. Benjamin Mays, warned that some church leaders were using “crooked” methods to suppress their religious rivals, much as some white evangelicals are reportedly doing today, from the Southern Baptist Convention to Liberty University.

Read More: Tim Alberta on What Fuels the Evangelical Devotion to Trump

Few were more dictatorial than the Rev. Joseph H. Jackson, a law-and-order conservative who, through decades of savvy infighting and manipulating Baptist rules, had dominated both his home church, Chicago’s Olivet Baptist—a megachurch with 20,000 members—and the National Baptist Convention (NBC), the umbrella organization for America’s Black Baptists. For years, Jackson used his unchecked power as President of the NBC to keep it on the sidelines of the civil rights movement, which he personally viewed as little more than “lawbreaking.”

Meanwhile, King hoped to turn the NBC’s 5 million members into foot soldiers for the Movement. And so, at the NBC’s 1960 convention in Philadelphia, King tried to oust Jackson through church democracy. As vice president of a powerful NBC board, King led a reform faction that accused Jackson of violating the NBC’s own constitution to stay in power. King and his allies got a court order to force an accounting of the NBC’s money as well as a real election, rather than bullying tactics and what King’s all-star legal team called “convention trick[s]”. But in the end, Jackson won, then stripped King of his NBC title, and consolidated his own power as President. The reformers left and established a new denomination, called the Progressive National Baptist Convention. This spectacular breakup of one of the biggest religious organizations in America raised two hard questions for millions of Black Christians: how far should the church wade into the affairs of this world—and who gets to make those decisions?

Ironically, to make sure his own home church was on the front line of the fight for democracy and equality in America, King fashioned his own ministry in undemocratic ways. In 1966, when members of Ebenezer Baptist Church murmured that he was pushing the church too far into civil rights activism, King replied from the pulpit that he was not going to “pay any attention” because God had anointed him to preach, not the members. “The word of God is upon me like fire shut up in my bones,” he declared. “And God has called me to deliver those that are in captivity.”

There was no chance that Ebenezer was going to fire King in 1966. Yet Black newspapers, church histories, and hundreds of lawsuits from courts across America show that for generations, churches had been turning out ministers who mismanaged church money, misread the Bible, or who bulldozed members in the name of God Almighty. If King had not been so famous, Ebenezer might have tried to turn him out, too. Many Baptists believed that God had not called their ministers “to deliver those that are in captivity”—at least not in the way King claimed.

Black history doesn’t offer a simple answer to the church’s twin crises of values and democracy. King pursued what most of us today consider the “right” values—opposing racism and hate—but he did it through both democratic and antidemocratic means. He used church democracy to try to enlist the NBC into the Movement, yet in his own church he demanded that members “cooperate fully” with his leadership. And when we look beyond the fight against racial injustice, we might disagree with some of the values King and other Black pastors held in the 1960s—for example, their sexism. Devout people will always sincerely hold different beliefs about what “justice” requires, and that can create ethical dilemmas and tensions within congregations. And it isn’t easy to discern when a worldly issue becomes a religious duty. But the Black church’s struggle over joining the Black freedom struggle makes some things clear. People of faith should make those decisions openly, collectively, and above all humbly—questioning themselves and their values, no matter how clearly they believe God has called them.