Connor Leahy remembers the time he first realized AI was going to kill us all.

It was 2019, and OpenAI’s GPT-2 had just come out. Leahy downloaded the nascent large language model to his laptop, and took it along to a hackathon at the Technical University of Munich, where he was studying. In a tiny, cramped room, sitting on a couch surrounded by four friends, he booted up the AI system. Even though it could barely string coherent sentences together, Leahy identified in GPT-2 something that had been missing from every other AI model up until that point. “I saw a spark of generality,” he says, before laughing in hindsight at how comparatively dumb GPT-2 appears today. “Now I can say this and not sound nuts. Back then, I sounded nuts.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

The experience changed his priorities. “I thought I had time for a whole normal career, family, stuff like that” he says. “That all fell away. Like, nope, the crunch time is now.”

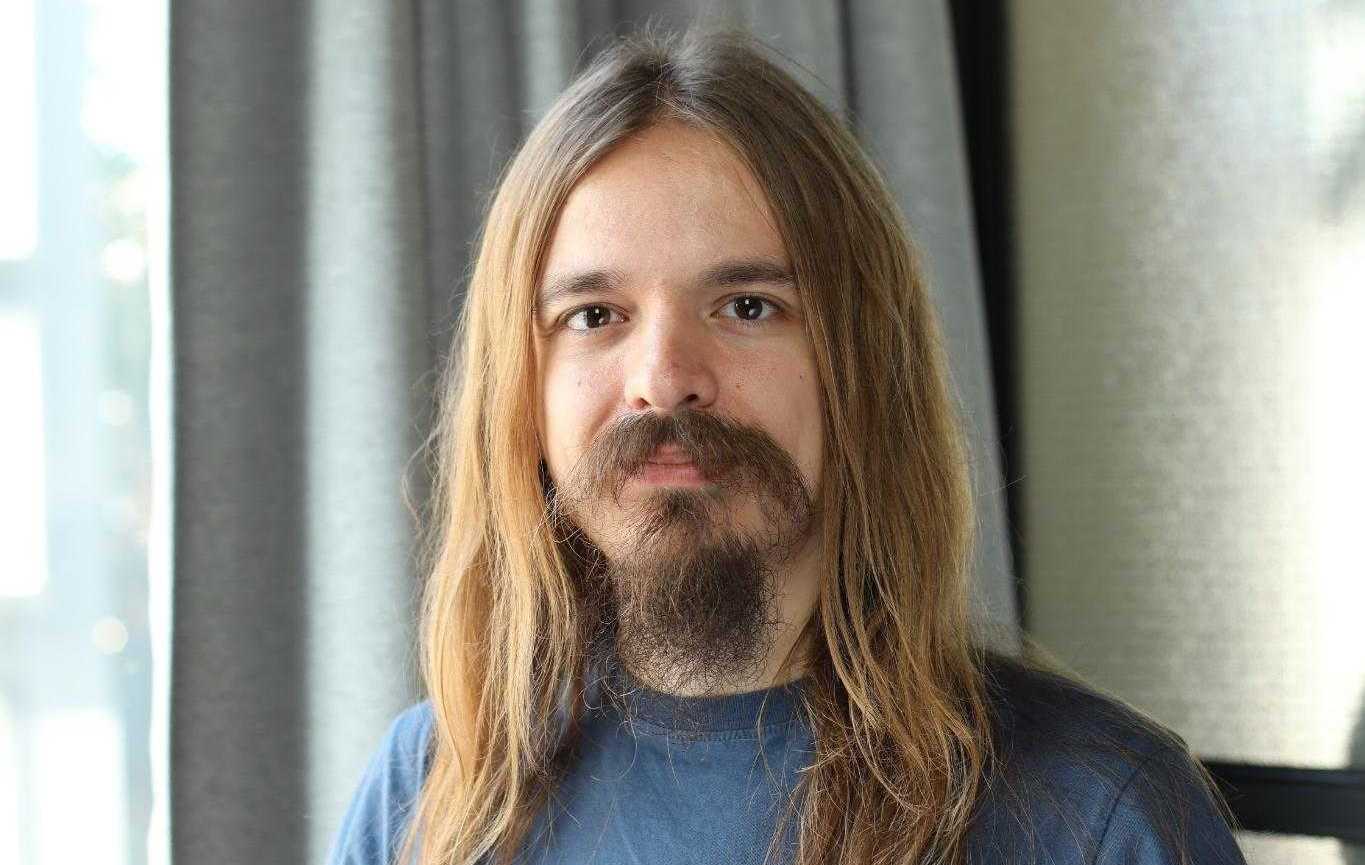

Today, Leahy is the CEO of Conjecture, an AI safety company. With a long goatee and Messiah-like shoulder-length hair, he is also perhaps one of the most recognizable faces of the so-called “existential risk” crowd in the AI world, raising warnings that AI is on a trajectory where it could fast overwhelm humanity’s ability to control it. On Jan. 17, he spoke at a fringe event at the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland, where global decisionmakers convene annually to discuss the risks facing the planet. Much of the attention at Davos this year has been on the spiraling conflict in the Middle East and worsening effects of climate change, but Leahy argues that risk from advanced AI should be discussed right at the top of the agenda. “We might have one year, two years, five years,” Leahy says of the risk from AI. “I don’t think we have 10 years.”

Despite his warnings that the end is probably nigh, Leahy is not a defeatist. He came to Davos armed with both policy solutions and a political strategy. That strategy: focus first on outlawing deepfakes, or AI generated images that are now being used on a massive scale to create nonconsensual sexual imagery of mostly women and girls. Deepfakes, Leahy says, are a good first step because they are something nearly everyone can agree is bad. If politicians can get to grips with deepfakes, they might just stand a chance at wrestling with the risks posed by so-called AGI, or artificial general intelligence.

TIME spoke with Leahy shortly before he arrived in Davos. This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

What are you doing at Davos?

I’m going to join a panel to talk about deepfakes and what we can do about them, and other risks from AI. Deepfakes are a specific instance of a far more general problem. If you want to deal with stuff like this, it’s not sufficient to go after end users, which is what people who financially benefit from the existence of deepfakes try to push for. If you as a society want to be able to deal with problems of this shape—which deepfakes are a specific example of and which AGI is another example of—we have to be able to target the entire supply chain. It is insufficient to just punish, say, people who use the technology to cause harm. You also have to target the people who are building this technology. We already do this for, say, child sexual abuse material; we don’t just punish the people who consume it, we also punish the people who produce it, the people who distribute it, the people who host it. And this is what you need to do iIf you’re a serious society that wants to deal with a serious digital problem.

I think there should basically be liability. We can start with just deepfakes, because this is a very politically popular position. If you develop a system which can be used to produce deepfakes, if you distribute that system, host a system, etc., you should be liable for the harm caused and for potential criminal charges. If you impose a cost upon society, it should be up to you to foot the bill. If you build a new product, and it hurts a million people, those million people should be compensated in some way, or you should not be allowed to do it. And currently, what is happening across the whole field of AI is that people are working day in, day out, to avoid taking accountability for what they’re actually doing, and how it actually affects people. Deepfakes are a specific example of this. But it is a far wider class of problems. And it’s a class of problems that our society is currently not dealing with well, and we need to deal with it well, if we want to have a hope with AGI.

With deepfakes, one of the main problems is you often can’t tell, from the image alone, which system was used to generate it. And if you’re asking for liability, how do you connect those two dots in a way that is legally enforceable?

The good thing about liability and criminal enforcement is that if you do it properly, you don’t have to catch it every time, it’s enough that the risk exists. So you’re trying to price it into the decisionmaking of the people producing such systems. In the current moment, when a researcher develops a new, better deepfake system, there’s no cost, there’s no downside, there’s no risk, to the decision of whether or not to post it on the internet. They don’t care, they have no interest in how this will affect people, and there’s nothing that will happen to them. If you just add the threat, you add the point that actually if something bad happens, and we find you, then you’re in trouble, this changes the equation very significantly. Sure, we won’t catch all of them. But we can make it a damn lot harder.

Lots of the people at Davos are decisionmakers who are quite bullish on AI, both from a national security perspective and also an economic perspective. What would your message be to those people?

If you just plow forward with AI, you don’t get good things. This does not have a good outcome. It leads to more chaos, more confusion, less and less control and even understanding of what’s going on, until it all ends. This is a proliferation problem. More people are getting access to things with which they can harm other people, and can also have worse accidents. As both the harm that can be caused by people increases, and the badness of an accident increases, society becomes less and less stable until society ceases to exist.

So if we want to have a future as a species, we can’t just be letting a technology proliferate that is so powerful that—experts and others agree—it could outcompete us as a species. If you make something that’s smarter than humans, better at politics, science, manipulation, better at business, and you don’t know how to control it—which we don’t—and you mass produce it, what do you think happens?

Do you have a specific policy proposal for dealing with what you see as the risk from AGI?

I’m pushing for a moratorium on frontier AI runs, implemented through what’s called a compute cap. So, what this would mean is, an internationally binding agreement, like a non-proliferation agreement, where we agree, at least for some time period, to not build larger computers above a certain size, and not perform AI experiments which take more than a certain amount of computing power. This has the benefit that this is very objectively measurable. The supply chain is quite tight, it needs very specific labor and abilities to build these systems, and there’s only a very small number of companies that can really do the frontier experiments. And they’re all in law-abiding western countries. So, if you impose a law that Microsoft has to report every experiment and not do ones over a certain size, they would comply. So this is absolutely a thing that is doable, and would imminently buy us all more time to actually build the long term technical and socio-political solutions. Neither this nor my deepfake proposal are long term solutions. They are first steps.

One thing that the people who are pushing forward very quickly on AI tend to say is that it’s actually immoral to slow down. Think of all of the life-extending technology we can make with AI, the economic growth, the scientific advancements. I’m sure you’ve heard that argument before. What’s your response?

I mean, this is like saying, hey, it’s immoral to put seatbelts into cars, because think of how much more expensive this is going to make cars, so fewer people can have cars. And don’t you want people to have access to freedom of mobility? So actually, you’re a bad person advocating for seatbelts. This might sound absurd to you, but this is real. This is what happened when seatbelt legislation was first getting introduced. The car companies waged a massive propaganda campaign against seatbelts. What I’m saying here is that if you’re making money, you want more money, and you want it as fast as possible. And if someone is inconveniencing you, you want to work against it.

But this is like saying, we should take the steering wheel out of the car, and add a bigger motor, because then we can get to our destination faster. But this is just not how anything works in the real world. It’s childish. To get to our destination, going fast is not sufficient, you also have to target correctly. And the truth is that we are not currently targeted to a good future. If we just continue down this path, sure, we could go faster, but then we’re just going to hit the wall twice as fast. Good job. Yeah, we are not currently on a good trajectory. This is not a stable equilibrium. And I think this is the real underlying disagreement is I think a lot of people just have their heads in the sand. They’re, you know, privileged, well, wealthy people who have a certain disposition to life where for them, things tend to tend to work out. And so they just think, well, things will just continue to work out. The world hasn’t ended in the past, so it won’t end in the future. But this is obviously only true until the day it’s wrong. And then it’s too late.

Are you more optimistic than you were this time last year, or more pessimistic?

I’d say I’m more optimistic about something actually happening in terms of regulation. I think I’ve been positively surprised by how many people exist who, once educated on the problem, can reason about it and make reasonable decisions. But that alone is not enough. I am quite concerned about laws getting passed that have symbolic value, but don’t actually do anything. There’s a lot of that kind of stuff happening.

But I’m more pessimistic about the state of the world. What really makes me more pessimistic is the rate of technical progress, and the amount of disregard for human life and suffering that we’ve seen from technocratic AI people. We’ve seen various megacorps saying they just don’t care about AI safety, it’s not a problem, don’t worry about it, in ways that really harken back to oil companies denying climate change. And I expect this to get more intense. People who champion difficult, unpopular causes are very familiar with this kind of mechanism. It’s nothing new. It’s just applied to a new problem. And it’s one where we have precious little time. AI is on an exponential. It’s unclear how much time we have left until there’s no going back. We might have one year, two years, five years. I don’t think we have 10 years.To Stop AI Killing Us All, First Regulate Deepfakes, Researcher Connor Leahy