June 12 marks the 57th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision Loving v. Virginia, deeming that state’s anti-miscegenation laws unconstitutional and affording mixed-race marriages legal protection across the nation. It also marks Loving Day, officially recognized by various governmental, cultural, and educational institutions to celebrate the 1967 decision and honor Mildred and Richard Loving, the couple behind the case.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Mildred, of mixed Black and Native American heritage, and Richard, white, challenged the local judge’s ruling after their arrest for violating the Virginia Racial Integrity Act, instituted in 1924. Accused of “cohabitating” in a union “against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth,” the Lovings were given a choice: accept incarceration for a year or leave the state.

The Virginia Supreme Court upheld the local judge’s decision: The state must “preserve the racial integrity of its citizens,” and guard against “the corruption of blood” and “a mongrel breed of citizens.” Eugenics supporters cast mixed-race unions as a threat to white “blood,” its inherent “purity,” and the health of the polity as a whole. But after the Lovings took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, Virginia’s anti-miscegenation act was struck down, along with similar laws that still existed in 16 other states (though neither South Carolina nor Alabama voted to remove statutes barring mixed marriage from their own constitutions until 1998 and 2000, respectively).

Today, recognizing Loving v. Virginia provides an opportunity to uncover a different, long-forgotten chapter in our nation’s long struggle with civil rights, interracial unions, and so-called racial “purity.” Twenty-five years before the ACLU took up the Lovings’ case, hundreds of mixed families faced a choice between home and marriage, freedom and love, under the shadow of the nation’s Japanese American incarceration camps. The policies identifying and policing these families were based on similar fears of non-white “blood” and its destructive powers against white bodies, minds, and American society as a whole.

Read More: The National Remorse That Follows Wartime Actions Against Civilians

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japan in 1941 and the U.S. entry into WWII, almost 100,000 U.S. citizens were among the 120,000 people of Japanese descent who were ordered “excluded” and “evacuated” from the West Coast. All were forcibly concentrated at inland camps. Not a single case of sabotage by an American citizen of Japanese descent was ever found. But the justification for this mass incarceration, as described by Colonel John Dewitt, head of the Western Defense Command (WDC), was that the “Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born on American soil…have become ‘Americanized,’ the racial strains are undiluted.”

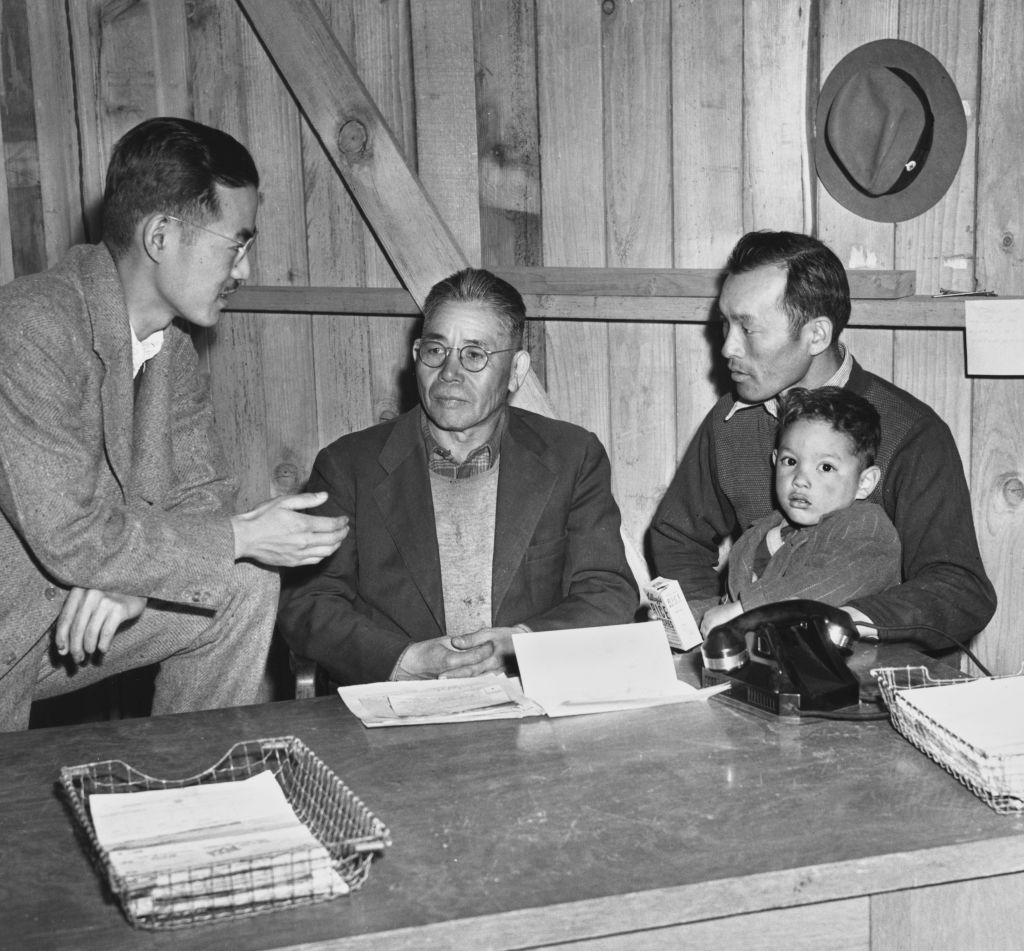

As the removal and incarceration of the entire West Coast Japanese American community began in the spring of 1942, administrators became confused about how to handle mixed-race families. First, the WDC mandated that any amount of “Japanese blood” counted as Japanese ancestry. Even orphans with only “one drop” were targeted for exclusion. But the WDC also claimed that the “evacuation” would “not split family units.” Administrators became stumped over how to balance these mandates.

One WDC solution, introduced that spring, was the “Request and Waiver of Non-Excluded Person.” Signing this form allowed non-Japanese parents or spouses to “request the privilege of accompanying” their family to a prison camp. The non-Japanese relative also agreed to “waive the right to leave camp” and to “conform in all respects as if [they] were a person of Japanese ancestry.” Here, the WDC asserted a new alchemy around race, peril, and freedom, whereby entering camp endowed someone, at least symbolically, with Japanese ethnicity, and thus rendered them a person in need of containment, an incarcerable body.

Throughout 1942, camp populations grew, including the number of mixed-race prisoners. That July, DeWitt approved a new policy, alternately called the Mixed-Marriage or Mixed-Blood Policy, spelling out who could apply for freedom, to be granted only after a rigorous review by both camp administrators and federal authorities.

Initially, the policy allowed families or individuals to apply for release based on a complicated matrix of both race and gender, reminiscent of policies from the early 1900s that punished women and men differently for marrying outside the boundaries of nationality and race.

Families composed of a white, U.S.-citizen husband, his Japanese or Japanese-American wife, and their children could return home to the West Coast if the “environment of the family” was deemed “Caucasian”—a requirement whose meaning no one really understood.

In contrast, a mixed family with a Japanese or Japanese-American husband, white wife, and young mixed-race children might be granted freedom if they could prove a “Caucasian” family environment—but only on condition that they relocated east. Otherwise, they would have to remain imprisoned. Mixed-marriage couples with no children had no recourse to release under the policy.

Read More: How Virginia Used Segregation Law to Erase Native Americans

A series of policy revisions ensued throughout 1942, 1943, and beyond, based largely on confusion over what constituted a “Caucasian environment.” Was it the way someone looked? The food the family ate? Administrators tended to consider these factors when assessing people’s applications for release, with a particular emphasis on who, in their words, looked “American” (meaning white).

And what about all the mixed families with no white members—which, to the government’s surprise, included a fair number? New iterations announced that a Japanese or Japanese-American woman, her non-Japanese but non-white husband who was citizen of a “friendly” country or territory (such as the Philippines), and their unemancipated mixed children might be freed as long as they resettled east. Non-Japanese mothers who were citizens of America or a friendly nation might be freed with their children and return home, but their husbands had to remain behind, incarcerated without them.

Other revisions mandated that mixed-race adults might be eligible for release only if their “Japanese blood” was either balanced or exceeded by their non-Japanese heritage, being “50%” or less.

Because the government’s data on incarcerees remains incomplete, historians will likely never know the exact number of people affected by the Mixed-Marriage/Mixed-Blood Policy during WWII. But most researchers estimate that over 2,000 people in mixed-race families among the West Coast Japanese American community were imprisoned for at least some length of time, including at least 134 with no Japanese heritage themselves, listed in camp records as “Caucasian” or simply “other.”

Many others without Japanese heritage remained outside of camp, enduring separation from their imprisoned relatives without knowing when or even if this separation would end. By late 1943, some portion of these families had an answer. That September, the WDC listed just over 554 people released through the policy and living on the West Coast. For others, their families remained fragmented until after the war ended and the camps closed.

Yet the legacy of the Mixed-Marriage/Mixed-Blood Policy endures, not just in the general intergenerational trauma of the Japanese American exclusion and incarceration, but in the forced family separations that, for many, could never fully be erased.

Even amid today’s celebrations of Loving Day, disturbing echoes of both the Mixed-Marriage/Mixed-Blood Policy and the laws overturned by Loving v. Virginia remain. We should remember both what has changed and what remains eerily similar still, echoed in rhetoric and violence born of fears over a “great replacement” changing the “racial mix of the country,” or how immigrants—many of whom have U.S. citizen children or spouses—are “poisoning the blood of our nation,” in the words of former president Donald Trump. But we can also hold hope: As suggested by the surge in mixed-heritage Americans following that critical Supreme Court decision, sometimes the human desire to merge overwhelms the forces that separate.

Tracy Slater is an American nonfiction writer in a mixed Japanese/Jewish family; Her next book, about the only known Jewish/Japanese American family in a U.S. WWII concentration camp, is forthcoming from Chicago Review Press in 2025.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.