Until very recently, you could walk into any restaurant, any bar, and make one simple request: “Tell me one whiskey or bourbon on your back bar that represents someone who is not a white male.” Then just wait while they look over bottles named for Jack, Johnnie, Pappy, and so on.

Before I started the Uncle Nearest Premium Whiskey Company, white males represented 30% of this country’s population and 100% of the available whiskeys—100%.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

The world has only learned of Nathan ‘Nearest’ Green, the first known African American master distiller in the world, in recent years. But to the people of Lynchburg, Tenn., his contributions to American whiskey were no secret. His family passed down the story of his mentorship and friendship with famed Tennessee whiskey maker Jack Daniel for generations.

But outside Moore County, Tennessee, Nearest was largely unknown—not unusual for a former enslaved person. In fact, if there is anything unusual about Nearest’s story, it’s that anyone knew it at all. Nearest couldn’t read or write and left behind no personal correspondence or journals; beyond a few county records and family anecdotes, there is very little to help us understand who he was as a person or how he saw his world. For decades, scholars have been trying to piece together African Americans’ many unacknowledged contributions to U.S. foodways—a difficult task considering that, for three centuries, records of Black people in America were erased, lost, or never collected in the first place.

So far, there have been five keepers of Nearest’s story—five souls, connected across a century, who’ve kept his story known. The first was Jack Daniel himself, who learned his trade directly from Nearest and worked with his sons after that. The second was journalist and historian Ben A. Green (no relation to Nearest) who published a biography of Jack Daniel in 1967. The book detailed Jack’s relationship with Nearest and would go on to be considered “the Bible” for the people of Lynchburg and required reading for executives at Jack Daniel’s. The third was Nearest’s granddaughter, Annie Bell Green Eady, who proudly told her many grandchildren all about how Nearest and his boys made whiskey for Jack Daniel. The fourth was Clay Risen, the New York Times journalist who wrote about Nearest in 2016 and ushered the story into the 21st century.

I’m the fifth. Clay’s article is how Nearest’s story found me. I may be in the spirits business today, but growing up in Calif., spirit had a totally different meaning. After my dad, Frank Wilson, moved away from his career as one of the original Motown hitmakers, writing and producing some of the greatest Motown songs of all time, to become a minister, my parents became teetotalers.

Read More: Meet the 31 People Who Are Changing the South

But it wasn’t just luck. I’ve paid close attention to true stories my entire life.

As a kid, I refused to read fiction. I never made it through a single novel by Judy Blume. Instead, I devoured Encyclopedia Britannica entries about actual people. I grew up listening to Smokey Robinson and Stevie Wonder tell stories at my parents’ kitchen table. When I left home at 15 and high school early into 11th grade, other people’s stories became my entire education. I read business books and memoirs and absorbed their wisdom. I listened while others spoke in the homeless shelters where I found refuge as a teen, trying to understand what we could do to change our circumstances. I read the Gospel, unfettered by my strict parents’ interpretation. And at age 20, when my first business venture faltered, I listened to my former employees’ critiques, studying my mistakes so I would not repeat them.

Throughout my entire professional life, I’ve tried to practice what Motown taught my father and what my father taught me—the significance of listening, empathizing, and seeing people’s hearts instead of their wounds. He taught me to see the world through the lens of grace rather than the prejudice of race.

So in 2016, when I first learned about Nearest, I knew I’d stumbled upon a damn good story.

I later learned that all five keepers of Nearest’s tale share the same birthday: September 5th. As I discovered each person’s date of birth, one by one, it felt monumental. It gave me chills and still does to this day. Annie Bell Green Eady was born September 5, 1901, and Ben Green was born a year later on September 5, 1902. And Clay and I are exactly the same age, born on September 5, 1976. No one has been able to say conclusively when Jack Daniel’s birthday is, but until the 2000s when Jack Daniel Distillery began celebrating the entire month as his birthday, the world celebrated Jack Daniel on September 5, with the exact year unknown. My research conclusively proved his year of birth to be 1848.

My life looks a lot different than it did back in 2016, but I’ve never doubted the rightness of raising up Nearest’s legacy and his amazing friendship with Jack. Both men were bigger than their time, and their actions reverberate on through today.

Telling stories like Nearest’s is part of reclaiming Black American legacies that have been lost, hidden, and destroyed. Against the white-washed backdrop of U.S. history, Nearest’s story stands out as the kind of example I longed to hear about and see, and I can already see the impact it’s having on others.

For Black History Month at E. A. Cox Middle School in Columbia, Tennessee, in 2023, the fifth-grade students made figures of famous Black Americans with Styrofoam heads sitting atop soda-bottle torsos. Students built figures like Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, and

Harriet Tubman. One little girl, whose father had recently taken our distillery tour, built Nearest Green. Principal Kevin Eady, who grew up just down the street from Jack Daniel Distillery, went to look at the projects and was shocked to see Nearest. “You may not believe this,” Kevin told the girl, “but I have a family relationship with him.” The next thing Kevin knew, he had 20 fifth graders crowded into his office, asking questions about his distant relation, about his dad—who had worked at the distillery—and about his cousin, Victoria Eady Butler, who is our master blender and Nearest’s great-great-granddaughter.

To hear Kevin describe the look on that fifth grader’s face, to discover just how much Nearest’s story has rooted itself in the imagination of the next generation, reminds me of what this all means. It excites me every day that this generation of Black children will have so many more examples of Black success and excellence in work and leadership than I ever had. To be able to be a part of that brings me immense joy. I’ve always said one of my superpowers is that, when I’m gripped by an idea, I find other people who are passionate about it and create a passionate community. Because of the Nearest Green Distillery—and the hundreds of people who have worked tirelessly to spread its message of love, honor, and respect—Nearest’s story is no longer in danger of disappearing. Instead, he has become the stuff of Black History Month projects, immortalized in Coke-bottle likenesses alongside Rosa Parks and George Washington Carver.

After over a century, he is where he has always belonged. And nearly a decade after he became part of my life, I can rest easy knowing he will never be forgotten again.

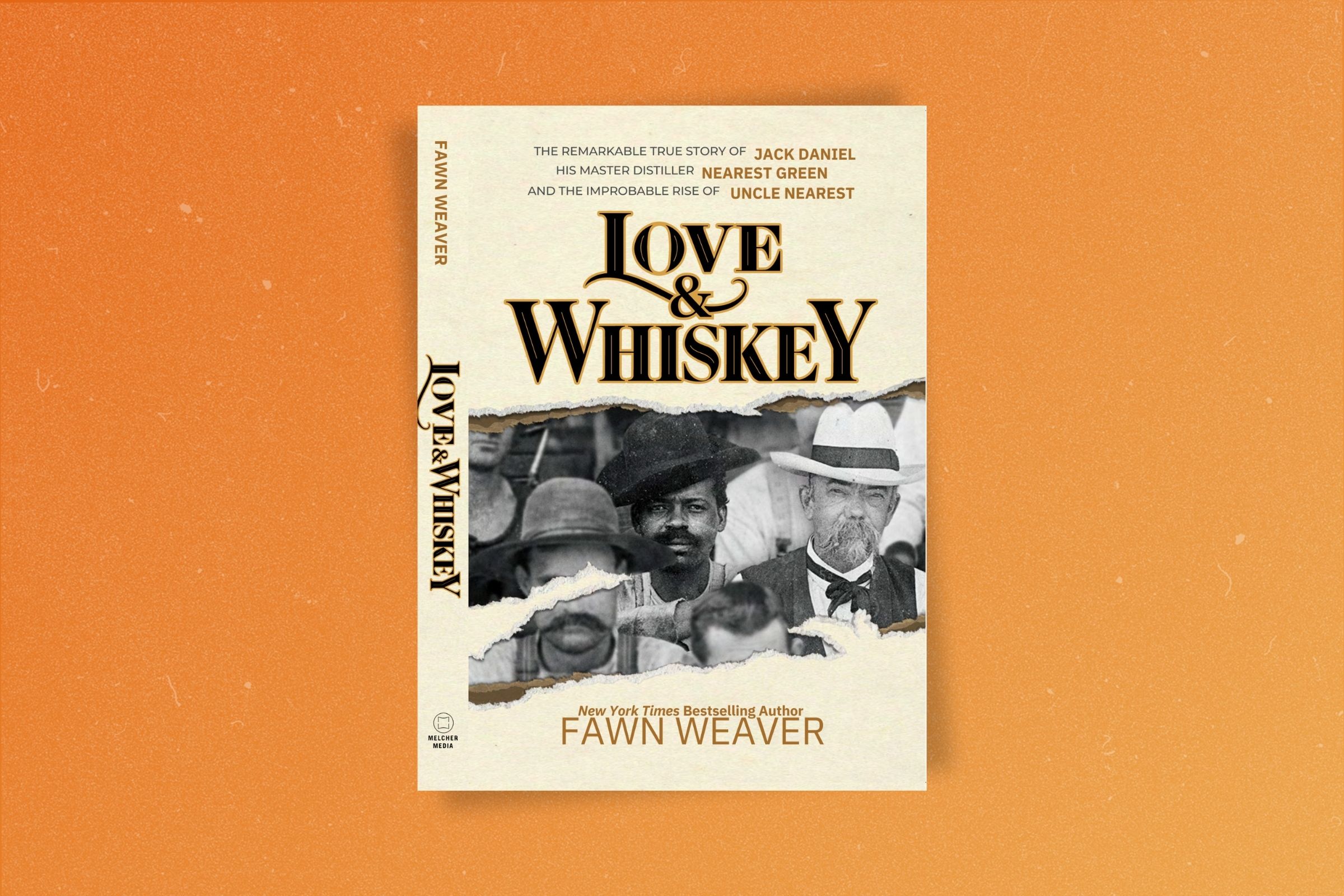

Excerpted with permission from Love & Whiskey: The Remarkable True Story of Jack Daniel, His Master Distiller Nearest Green, and the Improbable Rise of Uncle Nearest by Fawn Weaver (Melcher Media Inc, 2024).