There are many ways to debate whether former President Donald Trump is fit to lead this nation, but referring to him as a “convicted felon” does more harm than good. However, many political pundits and leaders use that phrase with intensity. It’s disheartening because I thought, as a society, we were moving towards using person-first language. And as a formerly incarcerated citizen, it stings.

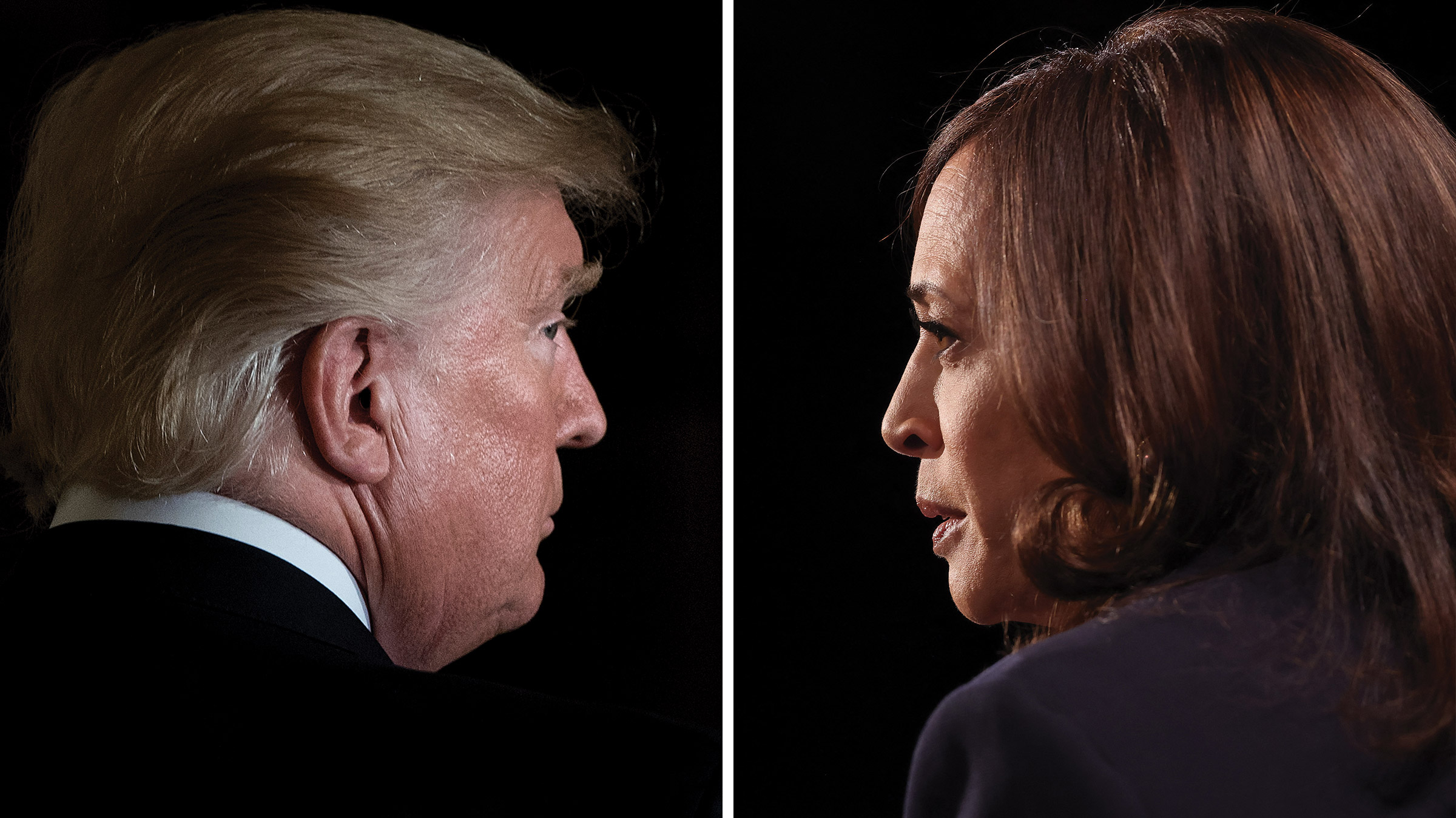

It doesn’t matter who is at the helm of either presidential campaign; I want all candidates to understand the harm in using this word. I held these sentiments when President Biden was the presumptive democratic nominee. And this matters to me now, with Vice President Kamala Harris as the presumptive nominee. I know political strategists and commentators look for catchy phrases to characterize their candidate. But no one should embrace “the prosecutor vs. the felon” narrative. That would be a mistake.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Nearly 20 million American citizens have a felony conviction, and 1 in 3 people across our country have some sort of record. Labeling people as “felons” or using the word as a badge of honor for political purposes is a slap in the face to the millions of impacted individuals and families. The truth is the label doesn’t harm Trump, as much as it harms the millions of other people living with felony convictions. It also represents a step backward at the very moment we should be moving our country forward. We can do that by embracing our shared values of forgiveness, redemption, and restoration.

Both campaigns have an opportunity to engage in a serious, statesman-like debate on issues. To resort to playground antics of name calling or reducing the election of the President of the United States to being a contest between a prosecutor and a “F-word” is robbing this country of the serious dialogue it deserves.

It also distracts from the greater task of uniting and healing the nation.

Read More: Can Kamala Harris Beat Donald Trump? Here’s What Polls Show

It’s important to remember that more than 600,000 people return to society from state and federal prisons each year. People caught in this system are easy targets to villainize because words like “felon,” “convict,” and “criminal” carry stigma. Those words provide an excuse to throw people away.

Returning citizens have learned that no matter how much they try to create a better life for themselves and their communities, many will still view them as unworthy of receiving an education, obtaining a loan, buying safe housing, or running for an elected office.

That has been my experience.

Despite all my accolades, I had trouble getting housing, insuring my home, and getting a bank loan. Yet, the most critical job in the world with access to the most sensitive information might soon be filled by a person with a felony conviction. How we speak about felony convictions depends on how much power and privilege one has. It’s a toxic narrative that hurts communities and families all across the country.

No one’s human rights should be denied. We just need to be honest about why certain people are excluded. The same support and grace that systems we show Trump should be offered to every returning citizen or formerly incarcerated person. We must call for a higher standard for everyone, and fight for all people to become whole.

This toxic narrative remains loud and clear on both sides of the aisle. In a Republican debate in August 2023, a moderator asked the candidates if they’d support a presidential nominee who’d been convicted of a felony, and six of the eight candidates raised their hands in support. If we support someone with a felony conviction moving into the White House, then shouldn’t we support policies that remove barriers to keep people like me from voting, getting a job, or obtaining safe and affordable housing?

This is so much bigger than some “prosecutor vs. felon” narrative.

Across the political spectrum, our political machine continues to feed into the same toxic narratives. This rejection of human rights is rooted in racism and classism. It also precedes violence.

Throughout history, we’ve seen how racist tropes were meant to devalue human life, triggering destruction and even death for groups of people. Elected leaders must hold themselves accountable for their complicity in continuing these harmful narratives. Just as returning citizens are expected to admit the harm they’ve caused and vow to do better, those elected to a high office should do the same. However, politicians have been quiet about many issues impacting our shared humanity, such as the 1994 Crime Bill, which destroyed many Black families, and the weaponization of words like “super-predators.”

I don’t tell people who to vote for, but I do advise people to vote with their conscience. I don’t judge people who are tempted to disengage from the democratic process altogether. But we still cannot sit this out. All hope is not lost.

But we should demand better. We must demand basic human rights and decency for everyone. If one group is dehumanized, no one is safe from dehumanization. We’re all connected. When we respond to hatred with more hatred, we perpetuate the very phenomenon we decry. We were brutally reminded through the attempted assassination of former President Trump how the decisive rhetoric of partisan politics serves no constructive purpose.

These distractions prevent us from having an earnest conversation about the language we use with each other and the narratives we let control us. It’d be a better world if we could learn to love who we despise the most. If we can do that, then we’re capable of loving anyone.

While I’m fighting for returning citizens and others affected by the justice system, I’m also fighting for everyone. We must get beyond feeling like we lose something when someone else is supported. The truth is, if my neighbor prospers, I prosper. No one wins if a returning citizen can’t get a job, housing, and education.

Recovery from this volatile election cycle won’t be painless. But those of us on the frontlines of our democracy are the heroes we’ve been looking for. We are the people who make this country work. We’re the lifeblood of democracy. I don’t know if we’ll have the same democracy—or get away from this harmful “prosecutor vs. felon” narrative—but I’m optimistic that something new and inclusive can be born from what we’re experiencing today.