This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. It is both All Saints’ Day and Fed day. This is just a coincidence, though if Jay Powell brings inflation all the way back to 2 per cent without causing a recession there may be talk of canonisation. Share your economic prayers with us: robert.armstrong and ethan.wu.

Japan: monetary policy reform and corporate reform

The Bank of Japan’s dismantling of yield curve control has proceeded a bit like a child eating a gingerbread house: the decorative candies are picked off one at a time before the structure itself is demolished.

So it was yesterday, as Kazuo Ueda’s BoJ nibbled at its 10-year yield cap, loosening it from a strict 1 per cent limit to a more flexible “reference” rate. In his post-meeting press conference, with the yen near a multi-decade low, Ueda said: “The reason why we made YCC more flexible is that we wanted to forestall the future risk of market volatility, including exchange rate volatility . . . [but] we still haven’t seen enough evidence to feel confident that trend inflation will [be anchored long-term at 2 per cent].”

Ueda’s ambivalence is understandable. On the one hand, as the Financial Times’ Chris Giles notes in his latest newsletter, core inflation in the city of Tokyo and nationwide have both looked firm. On the other, nominal wage growth still isn’t consistently beating the 2 per cent threshold the BoJ wants; the three-month rate is 1.4 per cent. Inflation may still largely reflect exogenous cost increases, rather than endogenous demand.

The BoJ may keep waiting and, in the interim, make operational tweaks to buy time. As Stefan Angrick of Moody’s Analytics argued in Alphaville recently, even the end of YCC probably won’t radically change 10-year yields, both because it would be replaced by regular quantitative easing and because Japan’s underlying equilibrium interest rate is low.

In the meantime, investors would be well served to pay closer attention to Japan’s corporate governance reforms, which will probably have far greater bearing on long-term equity returns than the country’s monetary policy. On that front, here is a good summary of progress so far. One Japan equity portfolio manager told the FT that shareholders believe they “will be sustained and that this time is different. If it turns out to be another false storm, that would be very disappointing.”

That quote, unfortunately, is from 2015, when Abenomics generated tremendous hype around Japanese stocks. So it makes sense that the latest Japan rally, and the corporate reform hype that has accompanied it, has attracted more modest enthusiasm from global investors. In 2013, net foreign fund flows to Japanese stocks totalled $153bn, calculates Nick Schmitz, Japan portfolio manager at Verdad Capital. Contrast that with 2023, supposedly a breakout year for Japanese stocks: foreign flows are under $40bn.

The comparatively slow start likely reflects what happened after Abenomics petered out: nearly all those $153bn in foreign flows fled the country between 2016 and 2020. Global investors, having seen this movie before, suspect the ending might be the same.

But this time, Japanese authorities are applying hitherto unseen pressure. Unhedged has repeatedly discussed the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s campaign, using the threat of delisting and name-and-shame tactics to get companies to shape up. In October, we complained that fewer than a third of listed Japanese companies have moved towards complying with the TSE’s reform guidelines. But another way of saying that is: around 1,000 companies in the rich world’s most calcified corporate culture have responded to the pressure. And that pressure is coming from all fronts. Meti, Japan’s economy ministry, in August published new M&A guidelines discouraging poison pill tactics and urging companies to take accretive buyout offers seriously.

The TSE’s ambitions are not just meant for the worst-run Japanese companies, those with a sub-1 price/book ratio. It is a broader campaign designed to raise returns on equity across corporate Japan, notes Atul Goyal, equity analyst at Jefferies. As the TSE’s chief executive, Hiromi Yamaji, told Nikkei Asia earlier this year:

“Instead of taking the rigid approach of saying those with P/B ratios below 1 have failed, it makes more sense to urge every company to make improvements,” Yamaji said . . . “We are not looking for a temporary response” focused only on measures like share buybacks and increased dividends, he added . . .

Yamaji compared Japan’s conundrum to the long-term downturn in the us stock market during the 1970s, dubbed the “death of equities” . . .

“Mergers and acquisitions started to pick up there thanks to Reaganomics” and inflation-busting policies pursued by then-US Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker, “which revived the stock market”, he said.

Most importantly, things have been changing on the ground. The share of Japanese companies with two or more independent directors has climbed from 22 per cent in 2014 to 99 per cent in 2023. The share of groups disclosing investor materials in English has climbed to 97 per cent, from 80 per cent in 2020. Company cross-shareholdings, a legacy of Japan’s development model, have hit a record low.

All this reflects the long shadow of Abenomics’ most lasting reform, a corporate governance code promulgated in 2015, as well as a deep, but slow-acting, shift in who owns Japanese equities. In the past three decades, as cross-shareholding has declined, traditional shareholders have gained ground. By one measure, their ownership share has risen 20 percentage points:

What unites YCC and corporate governance reform is a frustratingly gradual pace of change. But in both cases, the direction of change is plain to see. (Ethan Wu)

Valuing declining assets, tobacco edition

Last week I wrote about investing in declining businesses, in the context of the fund management industry. In that context, I mentioned the stocks of phone directory publishers, which I remember looking at years ago:

These companies’ revenues were in rapid decline, but they traded at price/earnings ratios in the low-single digits, with dividend yields of (as I remember it) 20 per cent or so . . . I don’t know what became of those companies, but I’m assuming it wasn’t good, and that it took less than five years.

In response to this, an Unhedged reader and leveraged finance veteran wrote to say he did know what became of those companies, at least in Europe. They got bought by private equity, and everyone involved lost money:

As a junior analyst in 2003, I was in my late 20s working in leveraged finance. The majority of the legacy European [directories] businesses were purchased by private equity and we provided debt at ~6x ebitda typically in €30mn+ bite sizes. The usual story (strong cash flow, strong balance sheets, good management, risk/return etc).

I pointed out that we should decline the deals as the internet was going to destroy the business model — ie no sustainable competitive advantage . . . Any-hoo: we all took a bath. The conclusion (across the majority of the syndicating banks) which managers claimed in credit papers was that a directory listing was a small charge for businesses — so why would they cancel it?

When they began cancelling in droves, the vast majority of the deals across the continent (we opted for senior debt rather than the [high-yield bonds]) were restructured, distressed exchanges or debt to equity swaps and we took an average haircut of ~25 per cent

It is very hard to value declining assets! Part of the reason, as illustrated by our reader’s crisp anecdote, is that when an asset looks cheap and still throws off cash, it is easy to come up with a story about why it will decline at a stately pace, rather than collapsing (“a directory listing was a small charge for businesses — so why would they cancel it?”).

This raises an interesting question: what is the 2023 equivalent of a yellow pages business?

While it has not reached anything like the phone directory phase, the biggest, most ambiguous, and most interesting example of a declining industry today is tobacco. Use of the industry’s core product continues to decline. Worldwide, more than a third of adults smoked in 2000; as of 2020, it was less than a quarter. But Philip Morris and Altria, by shifting their focus to countries outside the rich world and moving towards smokeless nicotine delivery, have managed to keep revenue flat (in nominal terms) over the past decade. British American Tobacco, with help from its 2017 acquisition of Reynolds, has done a bit better. Depending on what you think about the future of vaping, it is not hard to make a case that nicotine addiction, in any form, faces long-term decline.

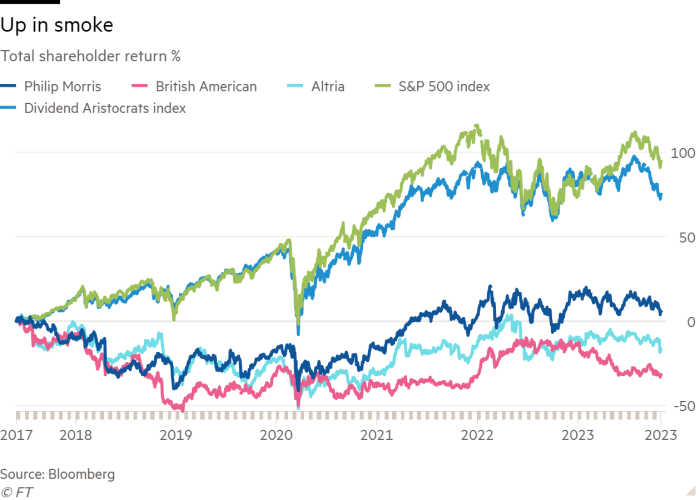

But can it still be a solid investment? Financially, big tobacco has adopted a cash cow strategy. The companies do not invest heavily internally and they devote basically all their free cash flow in dividends and share buybacks (Philip Morris, Altria and British American have dividend yields of 6, 10 and 9 per cent, respectively). For many years this worked. All three stocks kept pace with or beat the indices. Around 2017, however, the strategy stopped delivering for shareholders. Here are total shareholder returns for the three companies, compared with the S&P 500 and with US high-dividend-paying stocks generally:

Tobacco is clearly a stagnant industry now, and the stock returns in the past five years suggest it may slip into decline. It is therefore worth considering whether — like declining assets often do — the industry has become mispriced. It is a big question, in the sense that the three companies currently have a combined market value of $275bn. We are keen to hear from readers.

One good read

The worst-case scenario.

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, hosted by Ethan Wu and Katie Martin, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Checkout latest world news below links :

World News || Latest News || U.S. News

The post Japan is changing, slowly appeared first on WorldNewsEra.